Edited by Anna Mirzayan

Original Publish Date: 12/22/2021

Installation view of “Radial Survey, Vol. 2” at Silver Eye Center for Photography

Images provided by Silver Eye Center for Photography

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

The Radial Survey was initially conceived in 2019 as a response to the large-scale museum biennial exhibition structure. Highlighting places and people that are often overlooked in those wide-sweeping surveys, the Radial Survey is an important counterbalance to the oversimplification that is prevalent when speaking on contemporary art outside of New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles. The only qualification for photographers to be considered for the Radial Survey is that they are based within a 300-mile radius around the city of Pittsburgh — “the biggest circle that could be drawn without including New York City” according to David Oresick, Director at Silver Eye.

The show opens to a running start: eight selections from Raymond Thompson Jr.’s “Appalachian Ghosts” (2019). The series interrogates the history of the Hawk’s Nest Tunnel, a three-mile excavation that took place in his home state of West Virginia in the early 1930’s. The tunnel took three years to complete, and due to poor working conditions and improper safety standards, also took the lives of an estimated 800 primarily African-American migrant workers by way of silicosis — a respiratory disease developed from the inhalation of high amounts of the silica dust produced. In his images Thompson re-imagines the experience of these workers and the Hawk’s nest Tunnel in an effort to commemorate this history. The images depict the actions and effects of this work. Thomson photographs figures mounting ladders and swinging hammers, isolated Black hands caked with chalky powder, and in “Tunelitis #2” (2019), a section of a leafy plant that could function both as a visual indication of the abrasive nature of the eponymous condition and a representation of the bronchial network it effects. All of this takes place against stark black backgrounds, many of which are partially obscured by the ghostly white dust that clouds the air around them. By using tight-crops and omitting grounding elements, the artist transports viewers down into the tunnels with these men, where the dust that clouds the air serves as both a specter of the history it represents, and a representation of the continued obfuscation of the history depicted.

Raymond Thompson Jr., “Appalachian Ghosts” (2019), installation view at Silver Eye

Following Thompson Jr, the viewer is met with the work of Njaimeh Njie by way of 19 black and white photographs from her series “This is Where We Find Ourselves” (2021), each with accompanying handwritten text. The small-scale photographs are well-situated within vernacular photography, and — revealed through the aforementioned text — present the artist’s personal history against a Pittsburgh that, through gentrification and development, has drifted from what she once knew.

These small images are installed in a mirrored step-shape that take the formation of a fragmented skyline, a clever presentation of the city at large and a nod to the tension between what her home is and what she once knew it to be. But Nije does not take that burden of resolution on herself. Instead, she presents her work less so as a fight to be remembered, but as a decision to be. “This is Where We Find Ourselves” (2021) doesn’t seem to make an effort to save these places or to halt the forces that have re-shaped them — that would be futile, and Nije’s composure across the work seems to reveal that she knows this. Pittsburgh isn’t the first city to undergo gentrification and development and it won’t be the last, thus Nije does not set out to save the city, but to immortalize her experience of it. The work declares: “I will document what this was, what we were, what home looked like — so when it comes the time when maybe they are no more, there’s something to point to and say: this was who we were.”

Njaimeh Njie, “This is Where We Find Ourselves” (2021) (left), installation view at Silver Eye

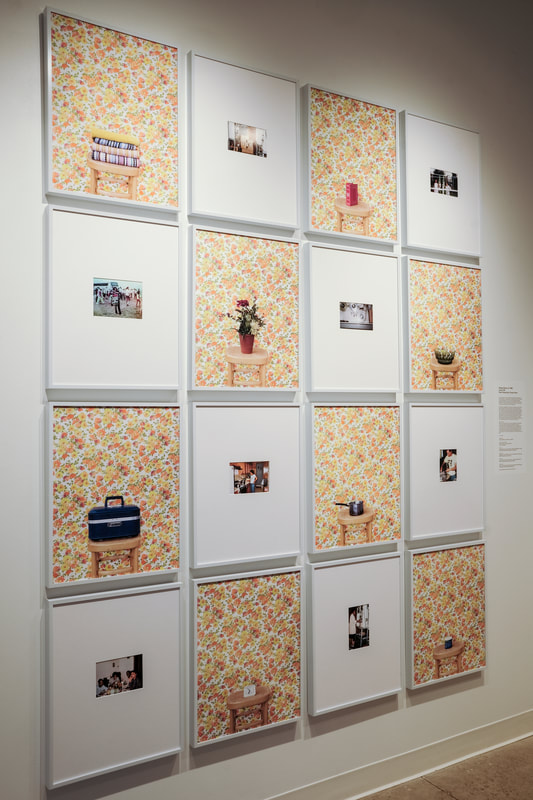

Nakeya Brown breaks step from the two artists that precede her, injecting vivid color in a presentation of created and archival photographs surrounding the history of labor of Black women in her family. At first glance Brown merely presents a portrait of a woman through her work and her possessions; displaying images of her grandmother in factories, at a protest or rally, and in and around the home inter-mixed with staged images of items that appear to have either belonged, or are simply relevant, to her against a bright floral backdrop.

Nakeya Brown, “Some Assembly Required” (2016), installation view at Silver Eye

Brown muddies this depiction with titles such as “Faking Flowers” (2016), “Assimilation Blues” (2016), “Depression Glass Bowl” (2016) — the last of which being especially potent in possibly referencing the era the object comes from (The Great Depression) or her grandmother’s state of being (depression). The collective presentation shows that while her grandmother’s labor may have been graceful as it extended through formal and informal places of work, that labor was potentially never-ending. Considering the well-documented conditions of Black womanhood, it is quite possible that this same burden has survived in Brown’s family in the same way that these objects have.

Jay Simple, “Exodus Home” (2020) and “Just MOVE (May 13th, 1985)” (2020), installation view at Silver Eye

In “Exodus Home” (2020), Jay Simple quite literally layers the past onto the present. Collaging archival documents and images onto found objects and the gallery walls themselves, Simple explores the Great Migration — a 50-year period in which African-Americans traveled North in large numbers in the hopes of prosperity and an escape from intense racial violence. Escape becomes a central theme in the work as Simple takes ownership of this history through its fragmentation and recombination. Viewers are met with an imagined history of an Apollo mission crew composed exclusively of Black women who are now central figures in this event. In drawing a parallel between space flight and northern migration for Black people, Simple positions both space and the North as aspirational freedom sites. But, as science and history show, both environments would provide their own threats to the livelihood of these astronauts — begging the question: where are we truly free?

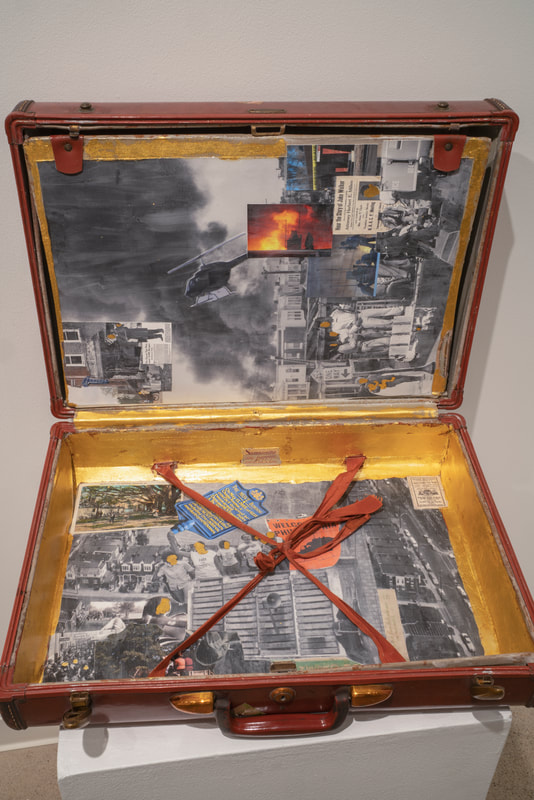

“Just MOVE (May 13th, 1985)” (2020) — the final work in the collection — is a suitcase into which Simple has pasted images of anti-Black police brutality. The sculpture shares a similarity with a number of objects in a museum of history rather than one of fine art, but among the objects in “Exodus Home” (2020) this work offers the viewer the clearest affordance of all; presented open and devoid of luggage, it can be read almost as an invitation to pour in your belongings and join the fictional astronauts or the very real Black migrants in doing as the work’s title suggests. But in Simple’s extension of this agency there is no opportunity to separate that invitation from all that is attached to it — talk about baggage.

Jay Simple, “Just MOVE (May 13th, 1985)” (2020)

Whereas Simple’s “Exodus Home” (2020) deals in a fantastical exploration of the extraterrestrial, we are brought firmly and heavily to the ground in Anique Jordan’s “Nowing: A Political History of the Present” (2021). In the installation, Jordan presents six photographs of issues of her local newspaper, The Toronto Star, all of which have been annotated with her own commentary.

Responding to headlines like “Council rejects motion to ask for 10% cut to police budget” and “Tracing COVID’s grim path”, Jordan is seen dealing in real-time with the precarity and systemic violence at the intersection of race and economic disparity in the context of a global pandemic. At times the notes are passionate and frustrated, at others inquisitive, and at some moments even reflect onto the work and Jordan’s practice as a whole (“‘Who gets the right to think of a future?’”). To read the issues, the viewer must position themselves at the wall with three steel silhouettes (from Jordan’s “BLK OPS” (2021)), each approximately 9’ tall, directly at their back — representations of Trinidadian Moko Jumbies which Jordan describes as “ancestral spiritual interveners.”

Anique Jordan, “Nowing: A Political History of the Present” (2021)

In this position, the silhouettes’ presence is felt, facilitating an intimate engagement with the photographs. From the alternate position where the silhouettes hang between the viewer and Jordan’s images, the role of these figures changes dramatically. Where they once hung as potential protectors, larger-than-life and watching over the viewer, they now are seen as permanent onlookers, frozen in observation of the state of things. From this point of view the physical presence of the figures has diminished, and with it their perceived — or maybe, desired — ability to intervene.

With Jordan’s frustration and exhaustion now in tow, Nadiya I. Nacorda’s images provide a moment of welcome rest, reprieve, and possibly hope, in an exhibition which has carried so much weight. Nacorda strings an intergenerational web of women in her family, herself included, across 10 original and archival photographs, Her subjects and settings are rendered in soft tones that make no grand statements, each frame holding its subject(s) tenderly and with full attention. The images are subtle and sweet, presenting a number of individual relationships that can be felt when viewing the photographs. In viewing Nacorda’s images, many of these women feel familiar — not because of any genuine familiarity with them, but because of the grandmothers, mothers, aunts, and cousins they recall.

But for all that is comfortable in this presentation of work, one photograph, “I saw her swallow all of her feelings inside her until they swallowed her whole” (2018), runs against the grain; depicting a clinical grin peeking through a slit in a large, inky green leaf, the image is unsettling. If the presentation of work can be seen as a “constellation” as it is described in the accompanying text, this image is the black hole at its center.

Nadiya I. Nacorda, “All Orchids Are Fine” (2018-2020), installation view at Silver Eye

The artist’s usage of a square crop leaves a viewer with few places to escape within the frame, and its central placement amongst the others keeps it in the viewer’s periphery no matter which image may be of momentary focus. Its demand for consideration is constant, and its title may be the only clue as to why. Nacorda provides no hints in the constellation of images or the accompanying statement as to who the aforementioned “her” is— Nacorda herself, another woman in the arrangement, or someone not pictured? Yet, when the artist pushes the viewer to contend with this image and its titular woman simultaneously with all of the other women and images in this body of work, we find that the gravity of the photograph lies in the consideration that it could apply to any and all of them.

In “Nothing of Weeds” (2017-2021), Ryan Arthurs imagines a space for a peaceful queer existence amidst the prolific right-wing ideologies that are prevalent in the rural areas near his home in western New York. Looking to cast the surrounding vegetation as a representation of these ideologies, Arthurs works to craft a series which makes visible the tensions between his queer identity and his surrounding environment. Presented in a symmetrical grid, these 12 images read as a narrative, wherein the viewer/photographer maneuvers through a bucolic forest setting to encounter an unidentified individual. In this encounter we witness the washing of a t-shirt and the removal of a jockstrap, which is then laid to rest upon a nearby rock — each moment followed by an image of a growing flame that takes over more and more of the frame with each subsequent appearance.

Ryan Arthurs, “Nothing of Weeds” (2017-2021), installation view at Silver Eye

The images are beautiful and the visual allegory is quite fun, but if tension between queerness and flora as a conceptual conduit for moral conservatism is a goal of this work, its focus may be misguided. The strongest element in this presentation of the work is Arthurs’ ability for visual storytelling. In only 12 images, Arthurs pulls off an impressive delivery of a succinct narrative with a clear beginning, middle, and end — his chosen setting working as a backdrop to queer existence, but never presenting as the threatening right-wing ideologies that plague rural queerness.

The show closes with selections from Hannah Altman’s series “A Permanent Home in the Mouth of the Sun” (2018, 2021). Foregrounded in her works are the symbols and cultural signifiers of her Jewish-American identity. Rendered through ephemeral mediums — patterns cut into hair, symbols pressed into the flesh of an apple and written onto the flesh of the body, and most wonderfully, a figure blowing a glass bubble — Altman communicates the preciarity of a culture rooted in diaspora. With no singular place of rest, these symbols, memories, rituals, and histories are at home in those who carry them on as a collective.

Altman’s voice rings clear across a seamless interpolation of her body of work, and that is a testament to its strength and clarity. Her images feel as if they have been born from a dream, but to say they are surreal or fantastical might be ill-fitting. Through her handling of light, be it refracted, shaped, or high in contrast; color; and subject-matter, Altman creates photographs where it becomes difficult to say for certain where reality stops and something beyond it begins.

Hannah Altman, “A Permanent Home in the Mouth of the Sun” (2018, 2021), installation view at Silver Eye

In its second iteration coming on the heels of a pandemic and resurgent civil rights movements, “Radial Survey, Vol. 2” asks not only which artists are making significant work within the determined region, but who is also making work that speaks to this particular moment. The response is a varied and punchy exhibition that is at times wonderfully imaginative, and at others, firmly grounded in the struggle of living as a marginalized person in this moment. In all instances, the exhibition gives a home — even if only temporarily — to eight artists navigating their own struggles for place geographically, culturally, and historically. Its specificity and concern with underrepresented locales is refreshing, and I look forward to Vol. 3.

Nick Drain is an artist and writer born in Chicago, IL, who lives and works in Milwaukee, WI. Centering his thinking around blackness, his work investigates the politics of visibility in an effort to illustrate the complex relationship of blackness and Black people to the object of the camera. Through image, sculpture, and writing, Nick rotates the triangular viewer—subject—maker relationship present in all instances of figural representation to place the Black subject at the top, thus reconfiguring the surveilling power dynamic between those who are privileged to observe by way of the white gaze and those who are rendered hyper-visible by their blackness. He has exhibited locally and nationally, most notably showing work at the International Center for Photography in New York City, NY, the Colorado Photographic Art Center in Denver, CO, and was named in the inaugural 2021 Silver List from the Silver Eye Center for Photography. Nick attended the Yale Norfolk School of Art in 2019 and received a BFA from the New Studio Practice program at the Milwaukee Institute of Art & Design in 2020.

Radial Survey, Vol. 2 is on view at the Silver Eye Center for Photography until February 19, 2022.