06/09/2022 Edited by Anna Mirzayan | Photos courtesy of the author and Gallery Closed

Rose Barba, silent (2022), press image courtesy of Gallery Closed

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

To say that Covid-19 irrevocably changed how we experience time feels a bit tired at this point—but it did. It placed creativity at the forefront of the need to take up this liminal and figurative space in innovative ways—to fill the hours and to make everything seem doable and achievable during this ongoing experience of the unknown during a pandemic. Nestled in the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Troy Hill and situated on the site of a former incline railway station, one particular art project, Gallery Closed, utilized this available space and time to make a conceptual reconfiguration of what we know to be a gallery space. I began this visit on a drive up Rialto Street, near where an incline trolley once trudged up and down the hill. I thought I had a good grasp on Pittsburgh until now, which slowly dissipated during my trek, even after countless hikes up hills that seemed too steep to walk up. My car chugged along slowly, giving me the irrational thought of it possibly sliding back down into the river. Lowrie Street was essentially deserted when I parked, save for one man sitting outside of a nearby building. It was misty, a little gloomy, and oddly ideal.

Gallery Closed stands out from the array of businesses on Lowrie Street, with its matte black facade reminiscent of a Louise Nevelson work; it alludes to the kind of monumentality that is hard to verbalize. It is unlikely that you will spontaneously arrive at the gallery from anywhere except for the crest of the cliffside upon which it rests; Rialto Street snakes up a steep cliffside along the Allegheny River. Pittsburgh is simply like this—houses and buildings sit neatly upon cliff sides of trees and craggy rocks with winding roads sitting flush beside every curve.

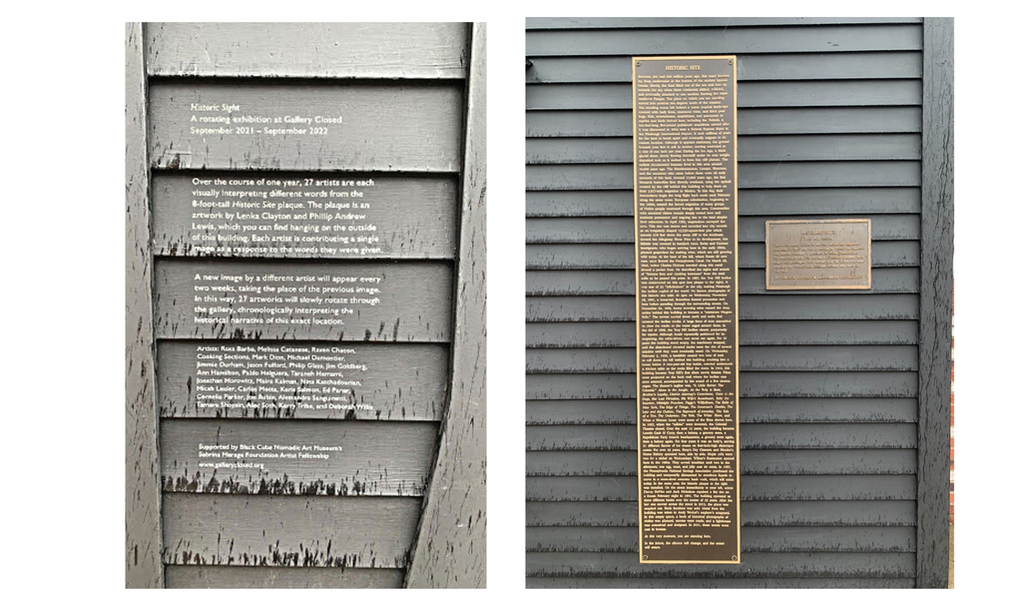

Gallery Closed was conceived during the pandemic by artists Phillip Andrew Lewis and Lenka Clayton (whose studios are housed in the building) with ancillary funding from Black Cube, an experimental nomadic art museum. The gallery, which also doubles as a permanent work of art in its own right, is currently home to two ongoing installations, Historic Site and Historic Sight, both of which can be experienced without entering the building itself. So how does a gallery stay open-yet-closed? As a current year-long exhibition and conceptual research project, Historic Site and the gallery itself are only intended to be experienced from the outside of the building and its storefront windows; immediately placing the viewer in the position of curious voyeur. This strange amount of distance pushes back against the typical proximity through which we mindfully view art, It also invites its audience to consider ideas of place and its deep historical roots through Gallery Closed’s exterior meditation on what it truly means to be a “historic site.”

Phillip Andrew Lewis and Lenka Clayton, Historic Site

(2021) and Pennsylvania Historical Marker, view at Gallery Closed, images courtesy of author

The Pennsylvania Historical Marker Program was created in 1913 to direct public and bureaucratic attention to sites of historical significance within the Keystone State.[1] Small, neat plaques stand alone or mounted on building facades from Pittsburgh to Philadelphia, leaving a curious passerby with a little more knowledge than they had before. Similarly, the Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation has their own distinctive plaques that dot Allegheny County to designate sites of note in the region; however, this endeavor does not protect buildings from future demolition.[2] The original plaque on the building that houses Gallery Closed has a concise description about its brief incarnation as the first station to transport railroad workers up and down the incline for two years until an expected closing.

A similar, yet much newer eight-foot-tall plaque alongside the original marker creates its own site of historical significance on the building that houses Gallery Closed. It marks the result of intensive research into the past of the building’s site itself by Lewis and Clayton, resulting in a rich historical narrative and an inferred ellipsis for its future. The description is speculative-yet-declarative, operating as certain and rigid despite the many what-ifs are left at its end. It is unmistakable that no Pennsylvanian marker is physically as long as Gallery Closed’s; reifying the notion of the historical marker perhaps calls to mind that history cannot be tidily encapsulated within a single, totalizing sentiment.

The marker’s narrative weaves through the prehistoric to the present and into the unknowable future. In order to craft this history, Lewis and Clayton spoke to numerous experts, piecing together threads of information about the location that touch upon numerous subjects; the marker speaks to the Indigenous stewards of the land and their forced relocation, Monarch butterfly migration trajectories, and dalliances with Hollywood stars. It also delves into the physical history of the space, which has a storied history as a silent movie theater, multiple banks, bakeries, restaurants, and grocery stores. The narrative is both factual and direct with a lingering tone of foreboding towards its end. Reading through this widely-unknown history of this building is an unexpectedly thrilling journey, leaving me breathless at its end.

Exterior of Gallery Closed, image courtesy of author

Gallery Closed eschews operating hours and traditions of opening receptions in favor of peaceful contemplation without the typical fanfare of the white box (and its restrictive open hours). The two rectangular windows that demarcate the interior gallery space create natural visual frames around the works inside. Historic Sight asks for an open interpretation of a word, or multiple words, from Historic Site, the aforementioned marker. Twenty-seven artist commissions are slated to be shown within the storefront by the end of the exhibition’s year-long run. During this particular weekend in April, Pablo Helguera’s As The Twig is Bent (2022) and Rosa Barba’s silent (2022) crossed paths–a new work is introduced every two weeks, displacing the one that has been there longer.

silent is an apt title when considering Barba’s work. The photograph depicts a rectangular box of light staged on a body of water’s surface during the evening. Whether the body of water is a lake, river, or ocean seems arbitrary in this instance; streams of reflective light mirrored in its surface wriggle down from the cityscape in the distance. The German-Italian artist’s practice is encapsulated in a simple, meaningful shot with cinematic staging positioned in a way that feels organic and natural. Most importantly, it portrays a landscape not unlike Pittsburgh’s; the silhouette of the mountains in the background dips down, allowing the few remaining clouds in the composition to peek through. There is the implication of movement without the need for a sequence of moving images.

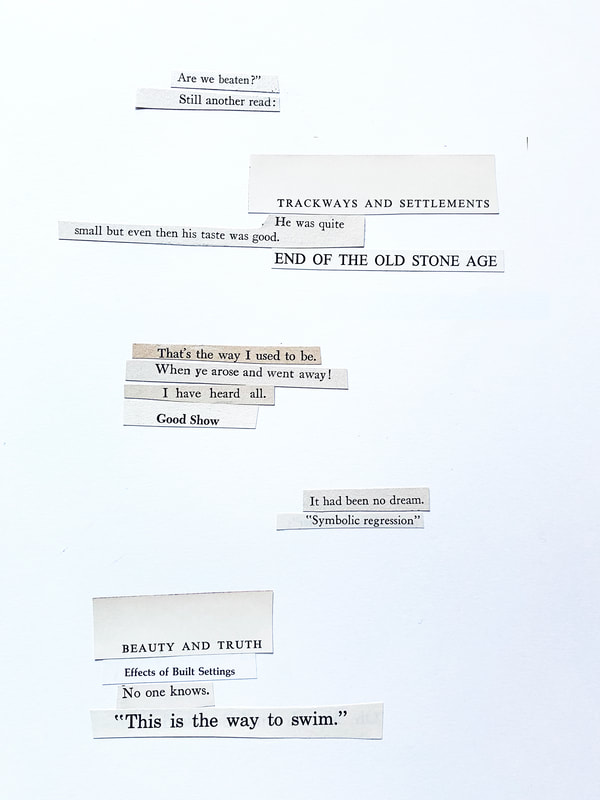

As The Twig is Bent captures movement through collage and prose, with fragments of wry phrasing that send the eye down the composition to its final sentiment: “This is the way to swim.” The text experimentally narrativizes the chronology of the Historic Site plaque, allowing an alternate experience of the passage of time within this specific location. Helguera’s practice largely investigates history, ethnography, and memory; this translates particularly through chosen phrasing, which explores notions of placelessness and post-colonialism. Clayton and Lewis’ willingness to consult with experts shines through within the massive plaque, and similarly, this comes through each related phrase and amalgamation of words carefully placed by Helguera.

Pablo Helguera, As The Twig is Bent (2022), press image courtesy of Gallery Closed

Gallery Closed effortlessly marries the intangible with the tangible simply through viewership and participating through this necessitated spectatorship with the simple act of looking through the two windows. The building mediates every glance, with either the plaques or the glass windows separating you from the interior of the space–which, frankly, is not what Gallery Closed is. The forced perspectives are always from a distance—through storefront windows—constantly shifting one’s ideas around the notions of place and space, and perhaps, the absence of both. A passerby may not even realize it is peripherally a gallery space—albeit a nontraditional one—until the gallery’s placard is seen off to the side of the storefront. In thinking about about windows as screens that mediate spectatorship (especially considering the relationship between many of the participating artists and the moving image), Anne Friedberg speaks to screens as “[marking] a separation—’an ontological cut’—between the material surface of the wall and the view contained within its aperture.”[3] The experience of viewing these rotating works is incredibly insular and introspective in spite of the forced distance and intangibility that ultimately comes with viewing art.

As I prepare to move away from the state I have called home through seasons of significant life changes, Gallery Closed serves as an encapsulation of every unique art experience I have indirectly shared with others in Pittsburgh. The project as a whole is a solitary, contemplative experience best meant to be turned over in one’s mind. What is the potential of a gallery that exists within and beyond a global pandemic? It is a site of art and history’s past, present, and future. Most importantly, it is a testament to the deep-rootedness of Pittsburgh as it straddles the midwest and northeast, as well as the rich history upon which Gallery Closed rests, symbolically signed by everyone who peers through its glass windows to see what awaits inside. [1] John Robinson and Karen Galle, “A Century of Marking History: One Hundred Years of the Pennsylvania Historical Marker Program,” Pennsylvania Heritage, Fall 2014, https://paheritage.wpengine.com/article/century-marking-history-100-years-pennsylvania-historical-marker-program/.

[2] “Historic Plaques,” Pittsburgh History & Landmarks Foundation, July 2, 2020, https://phlf.org/preservation/historic-plaque-program/

[3] Anne Friedberg, The Virtual Window: From Alberti to Microsoft (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 2006), 5.

Erin Gordon is an Austin-based writer and curator actively interested in the inextricable relationship between both practices. She received her MFA in Critical and Curatorial Studies from the University of California, Irvine and is pursuing doctoral studies in Art History at the University of Texas this fall. Erin is currently a co-editor of the art journal The Invisible Archive and a member of Philadelphia-based media collective Lino Kino. She misses Pittsburgh very much and hopes to return in the near future. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter @em__gordon__.

Historic Sight is a year-long exhibition featuring 27 artist commissions. The show runs from September 2021-September 2022 at Gallery Closed, located at 1733 Lowrie Street in Troy Hill.