Original Publish Date: 11/27/2020

By Nick Drain

Edited by Harrison Kinnane Smith | Published by Jessie Rommelt

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/937133344&color=%23ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true

Bunker Projects · What Are You Looking At? on Blackness, images and (in)visibility by Nick Drain

“I am invisible, understand, because people simply refuse to see me”

— Ralph Ellison, Invisible Man

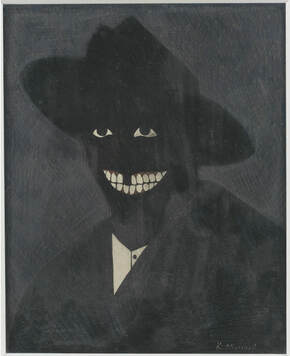

Kerry James Marshall, A Portrait of the Artist as a Shadow of His Former Self, 1980.

Credit: Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Since long before the invention of the photograph, the representational image has played a crucial role in the documentation and communication of what a society deemed to be most important. All the way back to the caves of Lascaux, images have shown us who and what societies valued, believed in, and how they saw themselves. In the nineteenth century, the invention of the photograph revolutionized the landscape of representation in a way that few other technological advancements have, and in doing so, enabled a far wider population to document what they deemed significant. Yet, like any other tool, the effects of its existence are not innately negative or positive, but a product of the wishes of whoever wields it — and it was not long before the photograph became a tool of epistemological violence in service of colonialism, surveillance, and other systems of oppression.

The technology that is race and the technology that is photography have become intertwined in their applications, the latter being imbued with the white gaze and used to further cement the former. The effect is that the biases of the white-hetero-cis patriarchy are carried both through the image and in the technologies which rely upon them. Consequently, Black people are increasingly rendered on one of two poles, invisibility or hypervisibility, suggesting a dangerous future. In this essay, I look to unpack these histories to make clear the violent impact photography and the image have had on Black populations worldwide, and inquire as to what Black people can do to shield themselves from this violence moving forward. What is the value of selective participation, mediated through the control of one’s own visibility? Are there ways to render oneself effectively invisible or semi-transparent at will, and can doing so be a way to counteract the violence continually done by the image on the Black subject?

In her seminal essay In Plato’s Cave, Susan Sontag works to unpack a number of ways in which photography as a practice, medium, and ontological framework have changed how individuals interact with the world around them — largely for the worse. Though she does not say so explicitly, many of Sontag’s critiques can be used to frame photography as an inherently violent practice. With these critiques, In Plato’s Cave can help us understand the three primary ways in which the camera, and subsequently the image, can and has facilitated violence on Black people. These are:

| 1. Violence through complicity; or non-intervention. 2. Violence through desensitization. -and- 3. Violence through (in)visibility. |

In her essay, Sontag identifies an element of aggression implicit in every utilization of the camera. She bases this reading upon the proliferation of a mentality in which the tangible world is always seen as the subject of a potential photograph — an imperialistic notion, compelling photographers to capture as many subjects as possible.(1) Violence is even present in the language we use to describe the making of photographs; photographers “shoot” subjects, “take” photographs, and “capture” likenesses. When photography is considered in practice, this underlying aggression is compounded. Sontag’s thinking becomes most potent when applied to photographs of suffering. Sontag identifies photography as “an act of non-intervention,”(2) stating that:

| To take a picture is to have an interest in things as they are, in the status quo remaining unchanged (at least for as long as it takes to get a “good” picture), to be in complicity with whatever makes a subject interesting, worth photographing -including, when that is the interest, another person’s pain or misfortune. (3) |

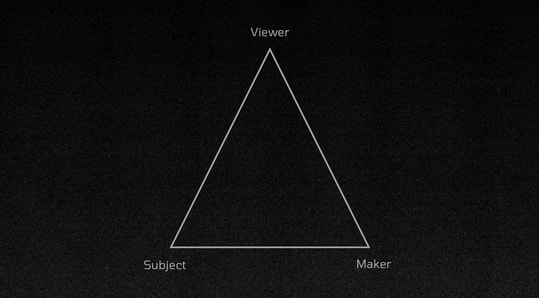

It can be argued that to make a photograph is an act of intervention through evidentiary means. Yet, there is a crucial distinction between direct and indirect intervention to be made here. Figurative representation can be thought of as a tangible instantiation of a triangular relationship between a subject, an image maker, and a viewer.

A graphic representation of the triangular relationship between subject, image maker, and viewer reified by figurative representations.

The photograph, which I posit as an act of indirect intervention, aims to mobilize the power of those who fall into the category of ‘viewer’ to act on the suffering of those who are rendered subject. This type of indirect intervention relies upon both the morality and capability of the ‘viewer’ (neither of which are ever guaranteed) to affect the conditions of the subject. The limits of this kind of intervention are determined by the viewer’s familiarity with similar images. Sontag accepts that visual evidence of an event makes it more “real” in the mind of the viewer, but at some point repeated exposure to a subject matter desensitizes the viewer — making the event less horrendous, and the images depicting it less impactful through their ubiquity.(4) This is violence through desensitization.

But the camera is not only a means to document violent atrocities. The interrelation of the technology of photography and the technology of race implicate the medium as an accomplice to racial violence. As a tool specifically used to better document and sort human differences, photography has been a main method used in colonialism to solidify ideas of racial hierarchy.(5) With each new expansion of photographic technology came new ways for the camera to operate in service of white hegemony. These technological advancements have worked primarily to situate Blackness — and therefore, Black people — on one of two poles: invisibility or hypervisibility. This is violence through visibility.

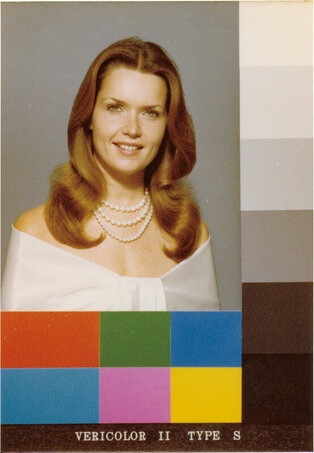

The technologies which have worked to enact these violences have taken on a number of different forms throughout photography’s first two centuries. One of the most prominent of these technologies, and most obvious in its fashioning of whiteness as the operational standard, was Eastman Kodak’s famous Shirley cards, produced from the 1950’s through the 1990’s.(6)

Shirley Card, 1978. Credit: Courtesy of Hermann Zschiegner

The Shirley card was a groundbreaking tool in color-balancing and exposure methods of the time, and other film manufacturers eventually produced their own versions of the form. Kodak’s in-house Shirley card did not feature its first non-white “Shirley” until the 1970’s, and as a result, darker-skinned individuals would regularly appear grossly underexposed in photographs. In extreme cases, the only details captured in images of Black subjects was in “the whites of their eyes and teeth”(7); poignantly recalling the punchline to a joke I encountered in my youth, which inquired as to how one could see a Black person in the dark.

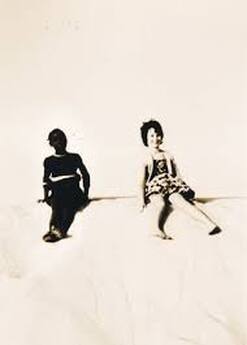

Two children in Senegal, (Natalie Le Brun [Right] and Guilado Sarr (or her sister) [Left]). Circa 1973. Kodak film (125ASA) used with Canon camera. A example of the challenge of photographing highly contrasted skin colours in the same frame and the difficulty of later recognizing who is in the photo (Courtesy of Olivier Le Brun, Paris, France) (via Lorna Roth, 118)

There were no issues of chemistry or physics which would have prevented film emulsions from accommodating this greater sensitivity from the start.(8) Yet, it would not be until receipt of the complaints of furniture manufacturers looking to more accurately document the detail and tone of dark-brown furniture, that the photographic industry would rectify this inherent bias built into their products.

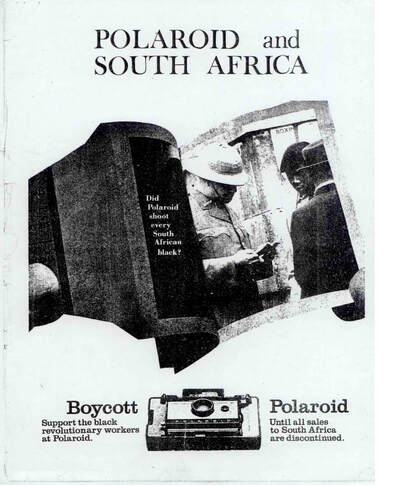

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, Apartheid’s grip on South Africa was at its strongest. By 1970, the most significant anti-Apartheid organizations — the Pan-African Congress, African National Congress, and South African Communist Party — were banned, their leaders either imprisoned or exiled from the country. Early in October of the same year, Ken Williams, an African-American photographer, Polaroid employee, and eventual co-founder of the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement, came across a sample identification badge for the South African Department of Mines while at work at Polaroid’s main headquarters in Cambridge, MA.(9) Williams would soon after discover that Polaroid’s ID-2 camera system was being sold to the white minority government in South Africa to aid in the creation of its infamously oppressive passbooks, a means of surveillance used to restrict the movement of Black South Africans throughout the country.

Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM) publication cover, 1971. Source: African Activist Archive.

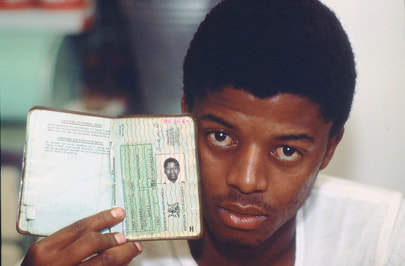

A Black South African showing his passbook issued by the government. Under Apartheid, Black South Africans were required to carry passes that determined where they could live. Photo:UN

The Polaroid ID-2 was a patented identification production system which could generate ID cards in a matter of seconds, and conveniently featured a flash boosting button that amplified the flash output by 42% — the exact amount of additional light absorbed by black skin. All Black South Africans were required by law to carry a passbook identifying their race at all times. Failure to produce one upon request resulted in fines, deportation from the area in which they were found, and/or immediate detention for an unspecified amount of time. Black South African thoughts on the ID-2 were poignantly mixed, with one individual subjected to the process stating “My pass, and the photo taken on a Polaroid, stand for injustice,” and another commenting, “The pass camera was good because it only took a few minutes of humiliation to get the picture done.”(10)

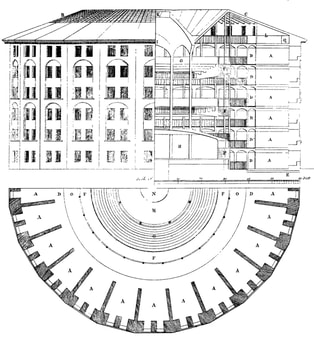

The histories of Eastman Kodak and Polaroid within the United States and South Africa, respectively, illustrate concretely two of the ways in which photography has continued to perform a kind of violence through visibility: via its affirmation of whiteness as standard, and obfuscation and illumination of Blackness on societal and state levels. In unpacking the relationship between state surveillance and the photograph, I find it productive to consider Jeremy Bentham’s concept of the Panopticon. The Panopticon, in short, is a theoretical penitentiary structure which arranges prisoners in cells forming the shape of a circle, and positions a guard in a central watchtower. The cells are illuminated but the central tower is kept in darkness, imposing an asymmetrical power structure through visibility. It is crucial to understand that Bentham’s Panopticon is not only applicable to prison architecture, but is illustrative of a hierarchical power structure dependent upon an imposition of visibility.

Plan of Jeremy Bentham’s panopticon prison, drawn by Willey Reveley in 1791. Photo: Wikimedia Commons

In Roy Boyne’s essay, Post-Panopticism, he sets out to complicate Bentham’s “Panopticon” and it’s adjacent terms by “drawing a black line through it, allowing the idea to be seen at the same time as denying its validity as description.”(11, 12) I argue for the extension of this black line, to — but not necessarily through — the site of the image in order to locate photography in its relation to surveillance practices and the efforts of state surveillance enacted upon Black people. Since the original French publication of Michel Foucault’s Discipline & Punish: The Birth of the Prison in 1975, a seminal text in surveillance theory, a number of different theoretical derivatives and alternatives have been produced to accommodate the continually widening landscape of surveillance studies, which now must encompass things like CCTV, advanced biometric identification, the invention of the internet, and subsequently, social media culture.(13) In the United States, the subjects of these surveillance tactics are frequently and disproportionately Black.

These practices are nothing new; in the United States, government surveillance of Black populations is as old as the country itself. A continuous thread runs through the implementation of lantern laws which restricted the movement of Black people in 1775, the FBI’s infamous attempts to disrupt the Black Panther Party in the 1960’s through COINTELPRO, and the leak of classified FBI intelligence documents assessing those they termed “Black Identity Extremists” in 2017. The latter two of these instances, as well as many which precede them, have been dependent upon the utilization of the image.

In Dark Matters: On the Surveillance of Blackness, author and professor Simone Browne invokes John Fiske’s argument that surveillance “has been racialized in a way that [Michel Foucault and George Orwell] did not foresee: today’s seeing eye is white.”(14) Fiske states that standard activities akin to running through a public outdoor space [as in the case of Ahmaud Arbery], exercising at a gym [Tyshrad Oates], or driving [Sandra Bland], or walking [Trayvon Martin] are perceived as unworthy of suspicion when performed by cisgendered white men, “whereas the same activity performed by Black men [or Black women and non-binary people] will be coded as lying on or beyond the boundary of the normal, and thus subject to disciplinary action.”(15) Cameras are not exempt from this perceptual bias. Arthur Jafa, in a conversation with bell hooks at the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts at The New School, inadvertently addressed these arguments and extended Fiske’s thinking to the camera explicitly, stating that “ if you point a camera at Black people, on a psychoanalytical level, that camera is also functioning as the white gaze; even if a Black person is standing behind the camera.”(16)

This becomes especially problematic when considering the faith we place in images. Though innovations in picture-manipulation technology have shifted our general perceptions of photography as objective, images still function in many spaces — as high as courtrooms, and as low as everyday conversations — as incontrovertible proof of the occurrence of an event; “pics or it didn’t happen.” When we are unsure of our ability to trust human perception of an event, we turn to the camera for the determination of fact and fiction.

On December 1st, 2014, after a grand jury decided not to indict Officer Darren Wilson in the killing of Michael Brown, President Barack Obama requested $236 million to invest in up to 50,000 body cameras to be worn by officers on duty. The Obama Administration seemed to believe that the existence of camera footage in police interactions with citizens would provide transparency in places which were once dangerously opaque. The camera would serve as a universal witness: corroborating the methods utilized by police officers in their apprehension of suspects when justified, and serving as testimony to hold the officers accountable in cases when they weren’t. Two days later, a grand jury in Staten Island elected not to indict Officer Daniel Pantaleo in the killing of Eric Garner; an event that was caught on camera. Tragically, this is all too familiar. The wrongful deaths of Alton Sterling, Philando Castile, Freddie Gray, and Eric Garner were all well documented. Yet, none of the officers involved in any of these killings would be convicted. The camera continues to be upheld as a standard of objective witness, yet when implemented in repeated attempts to keep Black people alive, or at least hold their killers accountable, the image continues to fail to serve as expected. In the words of Audre Lorde: “the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.”(17)

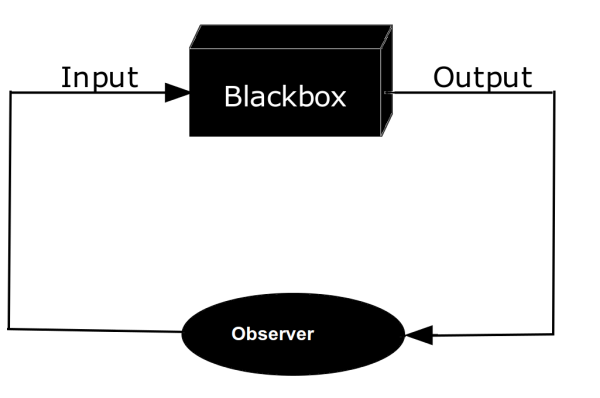

Much like its position throughout history, the current state of the image does not imply an equal future for the Black subject. Images, through their integral role within artificial intelligence and machine learning technologies, are working to shape the conditions of Black existence in more direct and wide-ranging ways than they ever have before. Over the past decade, artificial intelligence has been embedded within contemporary banking, hiring, medical care, and law enforcement practices, and the unchecked biases of their overwhelmingly white, cisgendered, and male creators are being built in right along with it. The result is a world of AI technology — and by extension, a future — dominated by a white hegemonic perspective. While the biases of their analog predecessors were able to be addressed through the removal of a problematic individual, artificial intelligence technologies cloak their biases behind a wall of complex code that can often only be understood as a series of inputs and outputs. In STEM fields, this is known as the “black box” phenomenon.

An illustration of the black box phenomenon. By Krauss – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=37353197

Everyday life is coming to be ever-more determined by image-reliant machines imbued with the biases of their creators. Creators who, due to a lack of awareness, perspective — or maybe even care — are crafting an AI-fueled future in which images will only continue to enact violence upon Black people. When society chooses to see the Black body punitively or not at all, it is imperative that we ask, what can be done to counteract this developing future?

To attempt to answer this question, it is valuable to return to the story of the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement (PRWM). At its outset, the movement demanded that Polaroid (1) publicly denounce Apartheid; (2) cease all business in South Africa; and (3) contribute money to recognized revolutionary parties in South Africa working to end Apartheid.(18) In the course of its seven year active period, the PRWM would garner wide-ranging support, receive recognition from a number of anti-Apartheid organizations across the globe, and galvanize the Boston higher-education community to perform a number of demonstrations opposing Polaroid’s involvement in the early 1970’s. The activism of PRWM co-founders Caroline Kent and Ken Williams would cost them their jobs at Polaroid, and they would receive no official credit from Polaroid in impacting the company’s eventual decision to withdraw from sales in South Africa. However, the momentum of their movement ultimately forced Polaroid to acquiesce to the PRWM’s first two demands. Polaroid pulled all of its business from South Africa in 1977, making them the first American company to do so, after years of failing to productively intervene against the segregationist government.(19) The PRWM exists in a rich lineage of Black organized efforts to address the oppression of Black people at the site of the photograph, and is one of the earliest organized efforts to address the role and participation of photography and photographic technologies therein. The PRWM leaned in, taking on Polaroid directly, and found success in doing so. But what is to be said of opting out — or rather, opting in-between, or opting under?

In Dark Matters, Browne coins the term “dark sousveillance,” an idea that has become instrumental in my attempts to locate answers to these questions through artistic practice. The root of Browne’s term, “sousveillance,” is borrowed from professor, engineer, and inventor Steve Mann, and can be understood etymologically as a composite of the French prefix “sous-” meaning “under” and root word “-veillance” coming from the French verb vellier, meaning “to watch.” Thus, Browne’s dark sousveillance expands upon Mann’s original term to describe “the tactics employed to render one’s self out of sight, and strategies used in the flight to freedom from slavery as necessarily ones of undersight,” with Browne identifying it:

| … as an imaginative place from which to mobilize a critique of racializing surveillance, a critique that takes form in antisurveillance, countersurveillance, and other freedom practices. Dark sousveillance, then, plots imaginaries that are oppositional and that are hopeful for another way of being. Dark sousveillance is a site of critique, as it speaks to black epistemologies of contending with antiblack surveillance, where the tools of social control in plantation surveillance or lantern laws in city spaces and beyond were appropriated, co-opted, repurposed, and challenged in order to facilitate survival and escape.(20) |

The practices of dark sousveillance, specifically the “tactics used to render one’s self out of sight,” when contextualized against the history and projected futures of Blackness in relation to the image, are the foundation upon which I situate my thinking and work on Black practices of selective visibility. In this work, I look to utilize the triangle as a means to map the aforementioned relationship between the viewer, subject, and maker; the transatlantic slave trade; the convergence of surveillance practices, the camera, and Blackness at the site of image; and the interaction between the histories of Black photographic representation, and the future of the image as a participant in contemporary artificial intelligence technologies. Through my work, I look to demonstrate the violent impact of the image in its relation to Black people; honor the methods of selective visibility that Black people have already come to practice; and imagine new ways for Black people to render themselves visible and invisible at will, rotating the viewer — subject — maker relationship to place the Black subject at the top, returning agency and power in doing so. Are the spaces in the blindspots of the white gaze big enough for us to self-determine? I cannot be sure, but there must be somewhere beyond the sight of the all-seeing aperture.

Endnotes

1. “In Plato’s Cave.” On Photography, by Susan Sontag, Penguin, 2019, pp. 3–24.

2. ibid.

3. ibid.

4. ibid.

5. “Coded Exposure.” Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code, by Ruha Benjamin, Polity, 2019, pp. 97–136.

6. ibid.

7. Roth, Lorna. “Looking at Shirley, the Ultimate Norm: Colour Balance, Image Technologies, and Cognitive Equity.” Canadian Journal of Communication [Online], vol. 34, no. 1, 2009, doi:10.22230/cjc.2009v34n1a2196.

8. ibid.

9. Morgan, E. J. “The World Is Watching: Polaroid and South Africa.” Enterprise and Society, vol. 7, no. 3, 2006, pp. 520–549. JSTOR, doi:10.1093/es/khl002.

10. ibid.

11. Boyne, Roy. “Post-Panopticism.” Economy and Society, vol. 29, no. 2, 2000, pp. 285–307., doi:10.1080/030851400360505.

12. First encountered in Simone Browne’s Dark Matters on the Surveillance of Blackness, published by Duke University Press, 2015.

13. Ibid. 38

14. Fiske, John. “Surveilling the City: Whiteness, the Black Man and Democratic Totalitarianism.” Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 15, no. 2, 1 May 1998, pp. 67–88., doi:10.1177/026327698015002003.

15. Ibid, 71.

16. hooks, bell. Jafa, Arthur. “bell hooks and Arthur Jafa Discuss Transgression in Public Spaces at The New School” YouTube, uploaded by The New School, 10/16/2014, https://youtu.be/fe-7ILSKSog

17. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches, by Audre Lorde, Crossing Press, 1996, pp. 110–114.

18. Williams, Amanda. “Golf Day Honors Ken Williams, Who Began Polaroid Revolution.” Vineyard Gazette, 21 Aug. 2008, vineyardgazette.com/news/2008/08/21/golf-day-honors-ken-williams-who-began-polaroid-revolution.

19. Morgan, E. J. “The World Is Watching: Polaroid and South Africa.” Enterprise and Society, vol. 7, no. 3, 2006, pp. 520–549. JSTOR, doi:10.1093/es/khl002.

20. Browne, Simone. Dark Matters on the Surveillance of Blackness. Duke University Press, 2015.