3/21/23

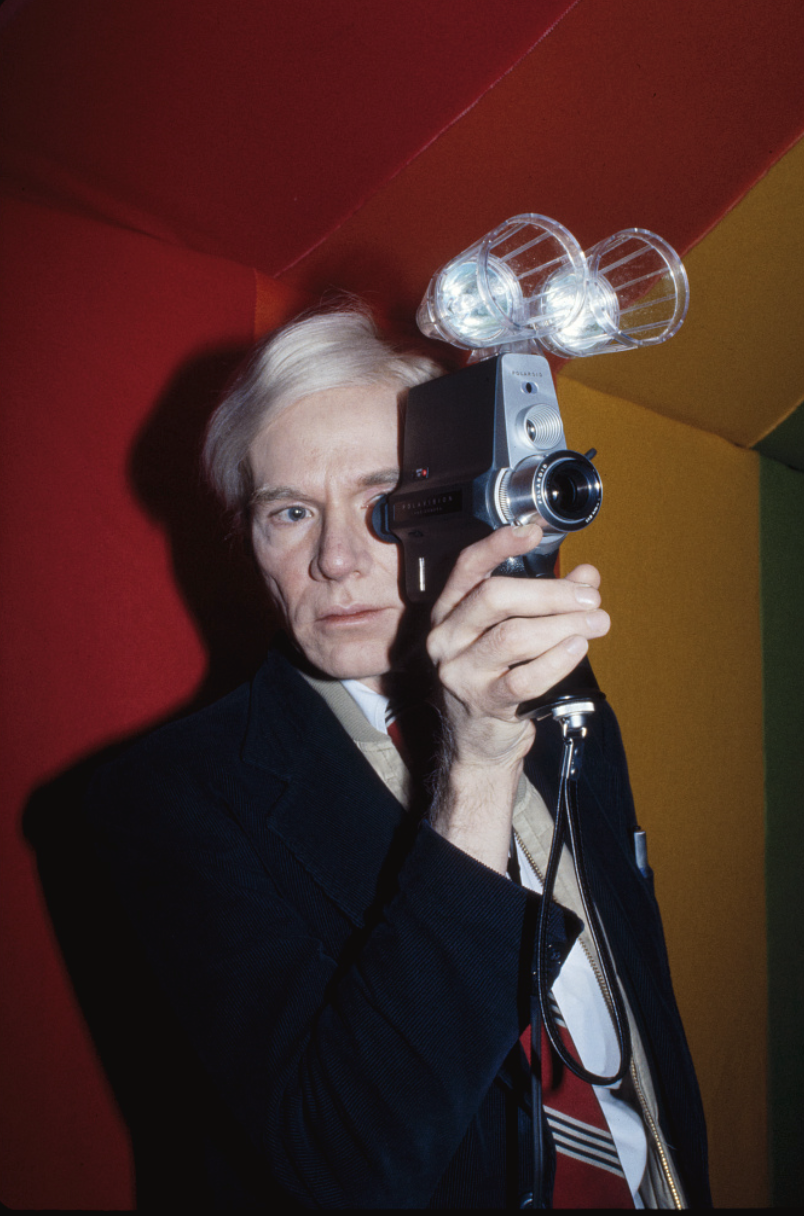

Bernard Gotfryd, Andy Warhol (ca. 1977), Library of Congress, LC-GB05- 4479 [P&P]

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

I have this, perhaps uniquely Pittsburgh, problem: I’m tired of Andy Warhol. I can’t go into a cafe without seeing a genuine, bootleg, or copycat Warhol canvas made in three or four combative hues. Every Halloween, scores of recent transplants to the city put on embarrassingly bad wigs and repeat an old liturgy about 15 minutes of something or another. Every bio blurb about the late Andy has some mention of Pittsburgh and how quickly he ran from here, as though that’s an interesting story, as though that’s not the story of our myriad parents, aunts, uncles, cousins… As though that’s not the story of coal, and salt, and glass, and iron, and steel. As though we don’t all run from Pittsburgh at some point. What’s interesting is coming back, or staying. Warhol didn’t do either. He moved to New York. Moving to New York isn’t interesting. He doesn’t really interest me. Or, maybe more precisely, a product called “Andy Warhol,” a sort of art world export, doesn’t interest me.

That product has most recently been exported to Saudi Arabia in the form of FAME: Andy Warhol in AlUla at the AlUla Arts Festival. Curated by Patrick Moore, director of our own Andy Warhol Museum, the show brings together a range of Warhol’s works that attest to his lifelong obsession with fame and the famous. In numerous interviews, Moore claims the theme of fame matches his own experience visiting the Gulf nation — a place imminently youthful, ripe for change, desirous of the eyes of the world. Housed in the Maraya — a stunning concert hall with a mirror-covered exterior — the whole shindig sounds utterly glamorous. Famous people, being looked at by the young and beautiful, inside a vision-defying piece of architecture on land ruled by an ultra-rich monarchy. I mean, pinch me! I think I’m dreaming!

Shockingly, I’ve not made my way to AlUla to see the show, but I suspect Moore succeeded at his curatorial goals. In interview, he says he wanted to introduce Warhol’s work through a concept (i.e. fame) to which young Saudis might relate. He wanted to build more rapport between the Saudi government and Western art institutions. Moore’s critics have pointed to Saudi Arabia’s repressive, anti-sex laws and the brutality of the Saudi government against its own people. I’m writing about these critiques the day after Tennessee banned gender-affirming care for transgender youth. I’m writing from inside a city so redlined and gentrified that ‘segregated’ remains a reliable way to describe the situation here. I’m sympathetic to Moore’s argument that it’s not right to deny an entire country the work of an artist on the basis of the actions of that country’s political regime. People in mirror-coated exteriors and all that.

Despite decades of change in the art world, it’s still a touch gauche to say “money” in a museum if you’re not in the gift shop or at an event for capturing techies’ wallets. Nonetheless, money and art are always in conversation: The Joan Mitchell Foundation is suing Louis Vuitton for reproducing her paintings in ads without permission. Mitchell’s paintings were on LV premises because they’d been loaned to give one name or the other more, renewed caché. And then there’s LV’s deal with Yayoi Kusama. And then there’s the woman who knocked over that $42,000 tchotchke in Miami. Every time we ask a question about the ethics of money in the art world, the sheer numbers make me think that nothing about these scenarios could be ethical even if it were Jesus lending out Moses’ artworks to Muhammad for 30 pieces of Judas’ silver.

When asked about the art ‘rental fee’ paid to the Warhol Museum by Saudi Arabia, Moore politely declines to answer.

I’m a lousy ethicist, so I can’t tell you if Moore’s right or wrong to show Warhol’s work in Saudi Arabia for an undisclosed sum. I’m pretty good at being gay, though, so I think I can tell you a few things about what FAME means for ongoing conversations about Warhol, images, and homosexuality. By homosexuality, I mean a complicated set of desires, affinities, and perspectives, that are never fully divorced from, but not always directly connected to, that most beautiful thing: gay sex. By all accounts, Andy wasn’t enthusiastic about doing gay sex, but that doesn’t matter. You don’t need to be enthusiastic about building internal combustion engines to use a car stereo. In this model of sexuality, the energy generated through reactions inside the mind/body isn’t just a genital-focused desire to have sex. It’s a more amorphous desire for bodily excitement, pleasure, creation, maybe destruction. The machine of sexuality is complex and the energy generated in all sorts of internal reactions can be routed towards activities and outputs that seem infinitely far from the continual hum of sex. That energy might fuel identifications with some kinds of bodies, some kinds of lives. For instance: famous, beautiful women. Andy wanted to be close to famous people, especially beautiful famous women. He wanted it enough, according to Moore and others, to uproot himself from the not-yet-rusted belt and devote years of his life to drawing women’s shoes and dresses, screen printing their multicolor visages, recording bits of saucy television and film with them. The pursuit of famous people, especially famous women, ordered his life as much as any desire to biologically reproduce, start a family, or establish a genealogical legacy. Andy’s desire for closeness with these women wasn’t made socially ‘good’ or important through sexual rapports or marriage. Likewise, Andy’s closeness to famous men became intensely socially meaningful when he depicted famous, sexy men (e.g. Elvis) as objects of desire. His desire, his sexuality, was a sort of open circuit. The numerous attempts to censor his work, pre- and posthumously, attest to the live desires channeled through Warhol’s pursuit of fame. Take for instance, the censoring of Warhol’s 1964 “Thirteen Most Wanted Men.” Although mugshots aren’t obviously sexual images, politicians readily detected in Warhol’s mural the possibility that fame/infamy and homosexual desire might mix. The men weren’t only wanted by the court — they were wanted by Warhol. Fame was inextricable from his sexuality and vice-versa.

In a 1967 critique of Warhol, Paul Bergin wrote that while Warhol pretended to be a machine — pretended to just export all the images he’d seen in everyday Americana — Warhol also admitted to producing images of what he ‘liked.’ Think Liz Taylor. A Brillo box. Machines, Bergin pointed out, don’t have likes or desires. So, Warhol couldn’t be a machine. I know I used the metaphor of a car for our sexuality, but for my earlier metaphor to be accurate, the car would need to be made out of melting Jell-O. Or half-frozen Campbell’s Tomato Soup. We’re all so messy, and no matter how much Warhol wanted to detachedly export the vocabulary of popular images that rumbled in his mind, desire was always slopping over the edge and staining the perfectly-printed image with desire. In pretending to be a machine, Bergin offered, Warhol was defeating himself by turning away from the editorial actions which made his work lively and interesting. In short: the images he chose to repeat were interesting because they had more than a trace of desire, of sexuality. Desire is scary. It asks for more than is sensible or economic, and Warhol’s desires were risky — at times illegal. Warhol wasn’t alone in wishing to be a machine and to be safe from desire’s pull, and FAME — as an exhibition, a press event, and a series of curator’s quotes — brings us back to the tension between wanting and being afraid to want.

In interviews with Arab Weekly and Art News, Moore tells us that Warhol was an artist, not just a gay artist. If we think of sexuality more broadly, though, we can see that Moore’s formulation is as impossible as it is inaccurate. Warhol’s work responds to his desires and the social conditions, which penalized, valorized, and ignored his desires. He wanted closeness with certain kinds of men and women, in arrangements that were socially unacceptable. In my lifetime, I’ve heard a few suggestions for what to call men with these desires, ‘gay’ being among them. Specifically, consistently, and despite censorship and harassment, Warhol stayed with his desire for the perfectly-polished face, the Vaseline-smeared lens on life.

What’s on exhibit at AlUla, then, is all sex, all desire. I don’t need to complain that Moore has elided Warhol’s sexuality because, in a way, FAME is the most homosexual exhibit he could mount. My complaint, instead, is that Moore doesn’t want us to see Warhol’s sexuality in Saudi Arabia. He wants to continue Warhol’s own project of licensing out the wig-wearing artist’s image to the highest bidder — no matter how much of Andy’s desire-drenched life the bidder wants to ignore.

I said earlier that I’m tired of Andy Warhol, but that’s not quite true; I’m tired of pretending that the longing tensions in Warhol’s works are settled. I’m tired of being asked to avert my eyes from all the aches on display. I’m tired of the well-oiled celebrity machine Andy wanted to be, that Moore’s statement needs Warhol to be, and that Pittsburgh hopes to become. What’s interesting about Warhol is that he couldn’t let go of desire no matter how hard he tried. I can’t let go of that Warhol. I’m never tired of that Andy.

Dani Lamorte

is a Pittsburgh-based artist. More: www.danilamorte.com.