The Imaginative Potential of Everyday objects: Do this while I wait at the Mattress Factory

By Cynthia Stucki with Lydia Rosenberg

Lydia Rosenberg, installation view of Do this while I wait (2023), Image courtesy of Tom Little

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

“I felt bad for the window glass.” …” It didn’t mean to kill the bird…It used to be sand,” he said. It remembers being sand. It remembers the birds, the way their feet felt, walking. Making little bird tracks. It never wanted to be glass. It never wanted to be sneakily transparent…”

Ruth Ozeki, The Book of Form and Emptiness, 2022

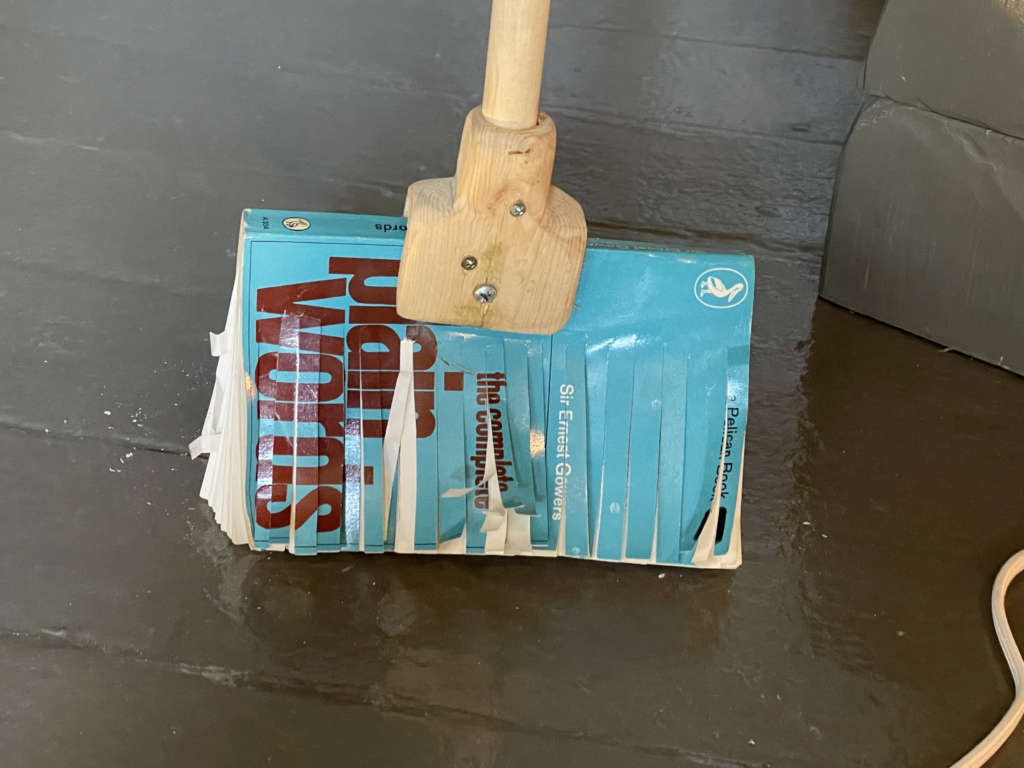

Most everyday objects have had alternate lives. Hastily used or lovingly adored, objects and their materials hold memories that trace transformative processes—rendering, extracting, melting, pressing, and mending. This informs what an object once was and continues to be as something we recognize, want, and need. Lydia Rosenberg’s installation Do this while I wait (2023) takes this concept of material transformation further by exploring the agency that objects have within our everyday. Presented throughout two dimly lit, gray-painted rooms in the Monterey Annex at the Mattress Factory, Rosenberg’s immersive setting invites visitors into a space of becoming or maybe unbecoming: being both, being multiple. In place of what we might consider domestic cleaning objects are instead-and-also: chunks of wood, a cluster of matchsticks, burnt carrots, shredded books, an instant vocabulary paperback, a pillowcase, a carpet, assorted houseplant roots, dryer lint, plastic shopping bags, and so on. Like peeling an onion into its many layers, this installation considers the nuanced meanings behind objects, the materials that form them, and how language is part of an object’s essence.

A conceptual counterpart of Do this while I wait is the artist’s ongoing project of a novel-as-sculpture, which Rosenberg has been writing in tandem with making since 2019. Entangled with her sculpture practice, the novel-as-sculpture expands on the imaginative potential of narration and creates mutable relationships between language and physical objects. Nuanced interactions of characters in the novel with objects and their settings are translated into physical manifestations through installations, sculptures, and performances. Excerpted from Rosenberg’s novel-as-sculpture, Do this while I wait depicts the mental landscape of Annette. This protagonist is an artist with a day job who can only spend eight hours a week in her studio because of her busy schedule. A very relatable experience for many artists! Due to a period of artist’s block, Annette listens to guided meditation audio files to find inspiration. These meditations create a narrative in which domestic cleaning objects become the key to decluttering her psyche. All the while, the installation at the Mattress Factory is the outcome of a failed attempt on Annette’s part to make her work; instead, Rosenberg has intervened to make the work that Annette hasn’t realized.

Scene from Lydia Rosenberg’s Spaghetti Restaurant (2019), Image courtesy of Jesse Ly

Lydia Rosenberg (LR): Annette is trying to empty her mind to gain clarity, which everything tells her is found in the practice of clearing. I don’t know if it’s a failure of mind over matter, but a realization that the mind IS matter and the matter of the mind is made up of the matter that surrounds us, even if it is distorted in the various lenses of the psyche, society, or whatever. The imagination is made up of what we put into it (something I heard Bekezela Mguni say in a talk she gave at CMU during the pandemic).

It’s really her failure to prioritize the studio and her practice that is in question. My relationship to the character of Annette is that I am making her work. She is seeing these tools in her meditation. Her goal is to empty her mind in hopes it helps her have an epiphany about what to make, but that’s exactly what she’s overlooking. Instead of seeing her meditated visions as viable prompts for artwork, she sees them as her failure to perform the exercise. I think I created this scenario with her because it’s what I sometimes want for myself, someone else to look into my life and say, “That’s it, that is the work you need to make right there, in that thing you are doing that seems like it’s irrelevant or wasteful.” But it never happens like that, so we have to make our projects happen on behalf of ourselves, we have to see the value, trust the threads of a process, and be convinced that failures get you closer to something that might feel successful.

I am also in love with how things turn out so differently in the real (even the digital/virtual) than they are in a mental image. Maybe this has to do with my perpetually novice-level craftsmanship in my case but I think most people who have tried to prepare a meal from a recipe know that things don’t always turn out the way they are imagined. There is another kind of doubling going on in this new project where there are the imagined tools and then the tools in the form of sculptures. In the novel, I never described the tools I ended up making so what you see in Do this while I wait is what I imagine Annette could be imagining. I will use descriptions of the sculptures to finish that section of the novel now that they are all made.

Lydia Rosenberg, The complete subject (2019), image courtesy of Ava Hassinger

The first sculptural iteration excerpted from Rosenberg’s novel-as-sculpture, The complete subject (2019), centered on a peripheral character named Joanne. She is a “narrowly focused middle age divorcee,” who obsessively writes descriptive journal entries of every painted image of a lemon she could find. While Joanne’s journal entries are ultimately written by other people by invitation of the artist, the sculptures of lemons presented in the exhibition were made independently of these journal entries. Spaghetti Restaurant (2019) was a performative installation that centered on the experience of characters in chapter two, all of whom have deep moments of contemplation while eating a bowl of spaghetti. This scenario was then presented in a storefront gallery that invited visitors to sit and eat a bowl of spaghetti.

As the characters and their internal struggles differ, so does Rosenberg’s approach to making and translating. The novel-as-sculpture becomes a source of collaboration alongside her explorations of language, representation, and material agency. Through fictional story building, in part influenced by sourcing quotes and ideas, Rosenberg embraces a multiplicity of relationships in her writing to create objects that have layered meanings—in the way that everyday objects and materials do. One way she does this is by using sculpture to emphasize the agency given to objects in her writing and text. Moving from text and imagination into a physical space creates a loop of meaningful transformations. These words on a page are used as a source for making objects and the making of objects influences the artist’s writing, which in turn moves the imaginative potential of the novel-as-sculpture along.

“She made a mental note of her schedule before sinking her

about Joanne, an excerpt from the novel-as-sculpture

fork into her pasta and pirouetting it around with three swift turns. She took

note of the ease with which she was able to wind up the perfect mouthful of

pasta and felt grateful for her years of experience that allowed her to perfect

her technique. Silly as it may seem, exercising this skill so effortlessly gave

her sense of good fortune and confidence that she took as a good sign of things to come.”

“She wasn’t thinking about any of this tonight. Her mind was blankly fixated on the undulating density of the plate of matter before her.”

about Annette, an excerpt from the novel-as-sculpture

“The next morning the plate of spaghetti was still sitting on the table and Annette woke up with Darien’s knee pressing on her bladder. In the bathroom she thought about hot house tomatoes and wondered if they felt patronized by the artificial summer they endured, forced into constant production with no real sense of life-outside-the-hot-house or the earth’s rhythms of growth and dormancy.”

Lydia Rosenberg, Spaghetti Restaurant (2019), Image courtesy of Jesse Ly

“Things are needy. They take up space. They want attention, and they will drive you mad if you let them.”1 This quote is from Ruth Ozeki’s 2022 novel, The Book of Form and Emptiness, and begins the artwork label for Rosenberg’s installation at the Mattress Factory. The quote considers the connection that people have to the objects around them and the attention they demand. We use a broom, squeeze lemons, eat spaghetti, sit on a chair, put things on a table, and push a vacuum. In many ways, part of our connection with the objects and things around us is our activation of them and their role (function) in our lives. Ozeki’s book is just one of many sources that has found a place in Rosenberg’s artmaking. Similarly, this text begins with an excerpt from The Book of Form and Emptiness where Benji, one of the main characters, recounts the material memory of the glass window in his classroom. He is acutely aware of the essence and series of transformations embodied in materials as they are shaped from one form to the next.

The quote that begins this essay is also one that the artist pulled from Ozeki’s book. Benji, one of the main characters, recounts the material memory of the glass window in his classroom. He is acutely aware of the essence and series of transformations embodied in materials as they are shaped from one form to the next. Attentiveness toward everyday objects and the possibility for words to explore material relationships is a consideration at the crux of this work.

LR: In life, most material is presented as if it has this limited process, for example, we think of wood as a product made from trees and not from forests. I am looking for an expanded perspective on the many relationships that enable things to come into being. The conditions for life have to be just right. The right things need to be born and die, to exchange food for fertilizer, to enter and return.

I have a wandering interest in materials that are the remnants of other processes like lint or food scraps, and metal bits from various machines. Part of this material focus is thinking about the idea of anything as a whole, complete thing, not something made of many assembled parts. This leads to ideas about waste, what is discarded, and what happens to things, the many shifts in value that an item and its material components go through. I love discovering things at the end of their life cycle, thinking about their material origins, thinking about human relationships to matter on earth, full of arrogance and brilliance. I think about my interest in materials as an exercise in how to preserve a moment of an object’s life cycle, how to prolong a phase of change, observant of entropy, consciousness-expanding and contracting at the level of all humanity, learning about mycelium, learning about strata, learning about other galaxies, learning how much is unknown.

Lydia Rosenberg, Do this while I wait (2023), Image courtesy of Cynthia Stucki

While talking with Rosenberg about her practice, she describes her process as convoluted, especially as her art-making is an entanglement of objects, materials, stories, essays, quotes, and friendships. Part of this convolution is her sensitivity to the complexity of everyday things coupled with an absorbing openness toward ideas and the people around her. Rosenberg’s novel-as-sculpture is a space for her to write about things that she might make, source together words and ideas, pull from personal relationships, and write about things that she has made. Her writing process acts as a container for meaning-making that simultaneously provides a context for moving objects along as they assemble form. There is a constellation at play where the artist’s writing and physical artmaking create connections that are then brought into a dialogue with one another. In the end, it is Rosenberg’s attentiveness toward everyday objects and the possibility for words to explore material relationships that present such a dynamic body of work.

LR: Each sculpture is drawn from a section of the novel but in some cases, it is drawn from multiple sections. I have been establishing the characters through the objects they are interacting with. In the first project, we learn about Joanne who is in search of every individual lemon represented in any painting. She doesn’t exist in one chapter but is scattered throughout the narrative. Another sculpture may be developed from her narrative arc as the writing develops, but her arc is first developed through The complete subject, the first project. She has other material and object stories she intersects with that are still in the works. The second project, spaghetti restaurant, conversely looks at a common object in the novel as you mentioned, a requisite for any character is that they have an introspective experience that represents some spectrum of human emotion as they eat a plate of spaghetti. I think with Do this while I wait, I am trying something new, developing a character (Annette) through my making of her sculptures. I think of each project as a sculpture, and the novel as a sculpture, two concurrent processes to think about sculpture and the making and meaning of objects.

In writing the text, I am working with the idea of a narrative driven by objects partly inspired by an essay by Soo Hwan Kim which describes Sergej Tretyakov’s idea of object biography. “Tretyakov’s ideas emerged as part of the so-called war with the novel. Novels are always psychological machines in which subjectivity and affect prevail at the expense of objects and objectivity. As Tretyakov writes, “In the novel, the leading hero devours and subjectivizes all reality.” However, the biography of the object is a powerful alternative method. “Thus: not the individual person moving through a system of objects, but the object proceeding through the system of people—for literature this is the methodological device that seems to us more progressive than those of classical belles lettres […]”2

Character is an odd aspect of this work that I am navigating. In my mind, the characters are just moving the described objects around in the narrative. They are malleable and serve the objects or future sculptures. However, in practice, I think something else is going on with the characters. They have started to take shape as conglomerated identities based partly in fantasy but also by incorporating other artists and friends and writers to whom I feel connected. These could be known art historical references but are often living artists whose works serve as inspiration for these merged portraits. This comes from thinking about the connective power of community to soften the feeling of the boundary between the self and what is outside of it. Seeing eye-to-eye as a way of seeing the self in the other.

In the novel the characters are all related to each other, making a family of ideas that may be expressed only in the writing or only in the sculptures, or sometimes in both forms. They are a space to explore the social dynamics of objects.

Lydia Rosenberg, Do this while I wait (2023), Image courtesy of Tom Little

Do this while I wait (2023) was one of three exhibitions presented in the Mattress Factory’s Monterey Annex exhibition space from March 3—December 30, 2023. Rosenberg’s exhibition was part of the museum’s 2021 Regional Open Call, which Denise Markonish, Chief Curator and Director of Exhibitions at MASS MoCA in North Adams, MA curated. The work will be traveling to the Bruce Gallery at Edinboro College, PA, and is on view from January 25—March 1, 2024.

Do this while I wait was on view through December 30th, 2023 at the the Mattress Factory.

Cynthia Stucki is a curatorial assistant for contemporary art and photography at Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. She has an MA in Curatorial Studies from the University of Zurich, Switzerland, and a BFA in sculpture from Florida Atlantic University, FL.

Lydia Rosenberg is an artist currently based in Pittsburgh. Her work, primarily in sculpture, is concerned with the impact of language on our perception of physical things. She received her MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from the University of Pennsylvania and a BFA in Intermedia from Pacific Northwest College of Art.