3/28/23

Banu Cennetoğlu, right? (2022)

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of the author.

I know it’s nearly over, but please let me tell you how much I hate this year’s Carnegie International, Is it morning for you yet?, the exhibition’s 58th iteration, which runs September 24, 2022 to April 2, 2023.

According to its website, the exhibition “traces the geopolitical imprint of the United States since 1945 to situate the ‘international’ within a local context,” and includes “historical works from the collections of international institutions, estates, and artists, alongside new commissions and recent works by contemporary artists.” It proposes the idea that a truly international exhibition, produced in the United States, must reckon with the United States’ legacy of Imperialism abroad, and that this legacy can be corrected, or atoned for, by bearing witness to it.

The show therefore includes artists from countries that the US has bombed, invaded, occupied, or “liberated,” in living memory, and my assumption here—it isn’t clearly stated—is that by doing so, the curators hope to center the perspectives of previously marginalized artists, in order to show how these countries, people, and cultures, are more than their historical trauma. Yet, by including artists solely because of their relationship to the US, the exhibition undermines its own goals. Instead of de-centering an American perspective, the exhibition firmly entrenches it, furthering the idea that these artists are only important because of the ways they’ve been affected by US intervention. In doing so, it also tacitly perpetuates the idea of an American audience that is removed from, and ignorant of, international history. This is a fictional, and wholly imaginary version of an American audience, homogenous and isolationist, who conveniently won’t see themselves reflected in the work, and can only participate as sympathetic observers.

I think that there is a version of this exhibition that might have been successful—one where the American imaginary perspective is effectively subverted, or destabilized. But in reality, the exhibition is overwhelming and crowded, and much of the included work is both uninteresting and inaccessible, relying too heavily on its political context without giving the audience enough to engage with aesthetically. Rather than truly creating an opportunity to delve into the represented global histories, what we get is a superficial gloss. Without effective curation, the exhibition comes off as disingenuous—somehow both self-flagellating and self-congratulatory, but lacking real self-reflection, and any real critique of American foreign policy.

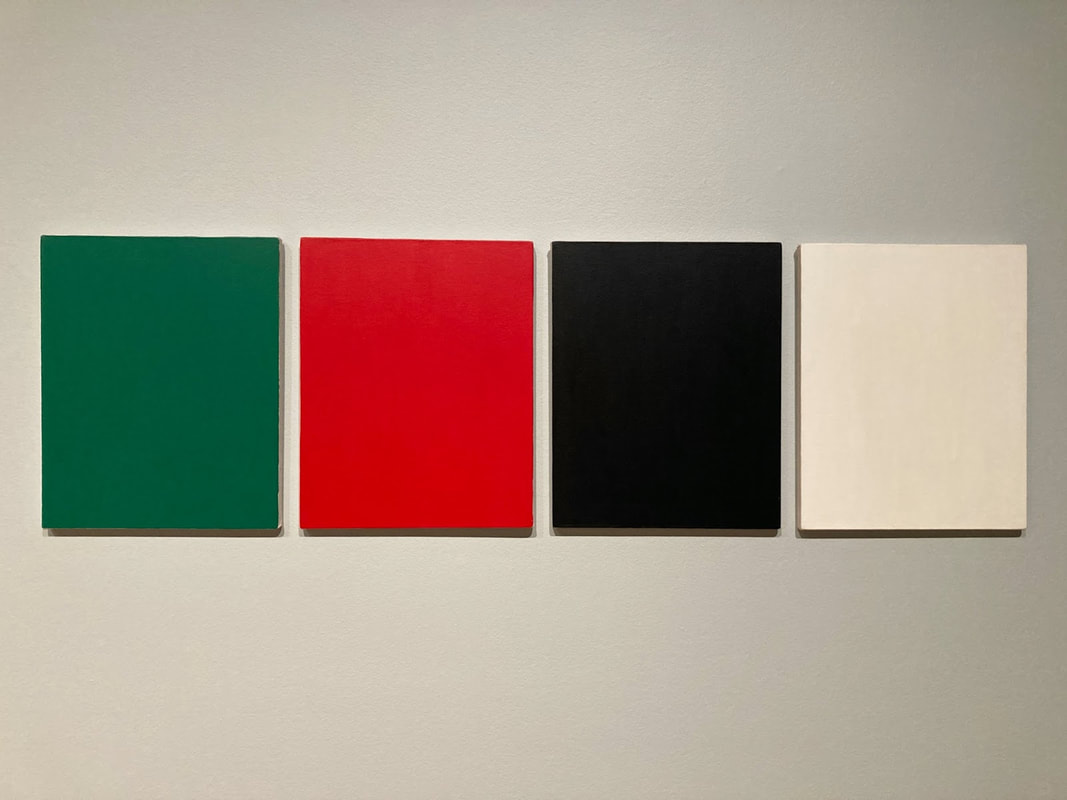

Félix González-Torres, Forbidden Colors (1988)

Throughout the exhibition, the curators consistently prioritize work that fits into their historical narrative over work that is visually interesting and engaging. The show begins with a mini-exhibition titled Refractions (2022), which presents historical works responding to U.S. global intervention, and is a preview of what’s to come in the main exhibition. There is a lot of work here—almost 200 small works by over 30 different artists and collectives—so it feels as if they’ve constructed a second, entirely new museum inside of the existing CMOA— one that feels more like a history museum than an art museum: there’s a lot to read, but not that much to actually look at.

Included in Refractions is Félix González-Torres’ Forbidden Colors (1988), a series of four small canvas panels painted solid green, red, black, and white—the four colors of the Palestinian flag. This work was made in response to the Israeli army’s 1981 ban on placing these four colors together (which was eventually lifted in 1993). The piece is a beautiful gesture of solidarity and protest, and it’s one of the more accessible works here, but it’s not visually interesting—it’s a purely conceptual piece. Given González-Torres’ reputation for conceptual work that is grounded both in powerful ideas and in evocative and beautiful visual metaphors, it’s also not his best work. And it’s difficult not to ask: Was it included based on its merit as a work of art, or merely because it fit into the curatorial narrative of inclusion and exclusion?

Tith Kanitha, untitled wire sculptures (2019-2022) and untitled works on paper (2020-2021)

The curators of this year’s International emphasize the political even when it isn’t relevant, necessary, or helpful. Tith Kanitha’s series of untitled wire sculptures (2019-2022) and accompanying works on paper are, to me, some of the least interesting in the exhibition, and the wall text doesn’t do anything to convince me otherwise. Rather than providing insight into her creative process, it contextualizes the work entirely in relation to Cambodia’s historical struggles against colonialism. The text treats the work merely as a placeholder for political content. At the same time that it talks about art-making as a way of being in the present, it ultimately roots Tith’s work in the past, and reinforces the idea that the work is only meaningful in relation to its history.

Eventually this reliance on historical context over the visual experience begins to feel claustrophobic—like a bad joke, or a recurring nightmare. I keep seeing the same thing, over and over. No matter where you look, all roads lead to “the geopolitical imprint of the United States since 1945.”

When I came to the exhibition’s opening party in September, the first works I saw were Hiromi Tsuchida’s Hiroshima Collection—a series of black and white photographs taken over several years, documenting objects damaged during the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. I left shortly after because I was so uncomfortable being at an event that was supposed to be a celebration, with these images adorning the walls. It’s not that I don’t like these photographs. Rather, it’s the fact that I do like them, the fact that they mean so much to me, that I found their presence in this context upsetting.

Hiromi Tsuchida, Watch (1982/2022)

In 2019 I visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, which houses all of the objects featured in the photographs. That trip was an important pilgrimage for me, and the experience of seeing these objects was deeply cathartic. But the Memorial Museum is a very different space from the CMOA, designed for a specific audience and a unique purpose—to preserve the history and memory of the bombing, to allow visitors to see and understand the horror of it (“skin so burned it was dangling in shreds…”), while also providing the space to mourn and to process grief. The Memorial Museum is also clear about its political messaging. It repeatedly argues that the only way to make sense of the bombing—the only way to truly move forward—is to fight for nuclear disarmament, and a world where this kind of violence cannot be allowed to happen again.

I felt embarrassed that I had to leave the party, but I was also really unprepared for the grief that seeing the photographs in that space would cause. I felt unsafe, and I felt angry that there wasn’t any space to process those feelings. When I did come back to the International in late October, and revisited these photographs, it wasn’t so much that I didn’t feel safe, but rather, that I felt like I didn’t belong there. I felt invisible and uncared for. When I look at these images I can’t help feeling like it could have been me. And it feels clear that the curators didn’t consider that someone might experience them as anything other than something to acknowledge—that someone might actually see themself in them, feel wounded by them, and feel hurt by that carelessness.

Removed from their context as historical artifacts, the images are presented as aesthetic objects— reminders of the past, sure, but reminders which have been transformed by the artistic process. And this decontextualizing in turn transforms the act of participation and understanding into an act of looking, and observation. It posits that there is political value in merely bearing witness, which absolves the need to question how global imperial power is upheld, to examine its deadly consequences, and to hold those in power accountable. It offers the careless opportunity to say: “Something bad happened here but at least something beautiful came out of it.”

Ultimately, this is the worst thing about the exhibition. Not that its curatorial conceit is bad, but that it’s false. That it gets away with claiming to participate in a conversation about what it means to “reimagine the world”, without actually doing any of the work of reimagining. It claims to center marginalized narratives by including historical and contemporary artists from around the world, but it presents their work in a critically detached way for an audience that doesn’t have a relationship to them. This only reinforces the Otherness of those represented and reveals the false narrative behind “representation”—inclusion alone cannot correct for exclusion when institutional powers consistently include marginalized voices only in order to excuse their own complicity in the power imbalances they ostensibly critique.

Hiromi Tsuchida, Suitcase (1982/2022) and Dress (1982/2022)

In almost every conversation that I’ve had, people have consistently said that the exhibition is too much, that it’s too heavy. When I asked some strangers at a bar if it was heavy, as in, “I feel challenged intellectually and emotionally and better prepared to respond to the world,” or heavy, as in, “I feel tired and just want to go home and watch TV,” they quickly agreed that it was the latter.

This is so disappointing to me, and makes me question whether the curators actually thought about their audience at all. So concerned with highlighting excluded histories, the exhibition doesn’t take into consideration its audience’s ability to actually take in and engage with these histories, and therefore fails to perform its fundamental function as an exhibition: to bring together artworks in a way that helps an audience better understand where they came from, how they came into being, and what this can tell us about our past, our present, and our future.

There is a lot that would need to change for this exhibition to work. But I think that most importantly, it would need to acknowledge that art doesn’t need to be overtly political in order to be politically meaningful. An exhibition that understands the political power of art must understand that art, and artists, are multi-dimensional—that what makes art powerful is that it can be many things all at once, and to different people. To present such a limited ideology takes away the viewer’s ability to engage with the work in a meaningful, open-ended, and expansive way. It devalues the work in the show and undermines the story that the show is trying to tell, but it also devalues—and misunderstands—the purpose of art itself.

The Carnegie International is the longest-running North American exhibition of international art. Established in 1896, the International runs every three to four years and shows the works of global artists responding to key critical questions of the time. The 58th Carnegie International was organized by Kathe and Jim Patrinos Curator Sohrab Mohebbi, and is on view at the Carnegie Museum of Art through April 2nd, 2023.

Brent Nakamoto is a Queer, Japanese-American, Buddhist artist, with a background in painting and drawing, printmaking, photography, and book arts. He received his BA in Art from UC Santa Barbara in 2012 and MFA in Visual Arts from the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts at Washington University in St. Louis in 2018. He currently lives and works in Pittsburgh, PA, where he teaches at the Carnegie Mellon University School of Art and is the Program and Marketing Coordinator for Brew House Association. He has shown work nationally and internationally, including in California, Saint Louis, New York, Pittsburgh, and Kolkata, India. His work is included in the University of Maryland Art Gallery permanent collection.