1/27/23

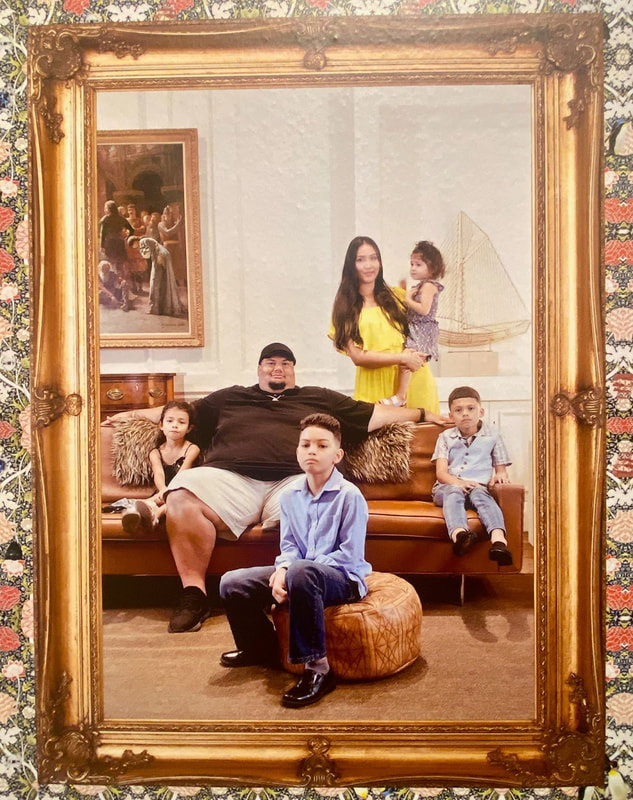

Gavin Benjamin, Christine and Tricia, Greensburg, PA, and the artist (2021)

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of author.

At the Westmoreland Museum of American Art, Pittsburgh-based artist Gavin Benjamin has carved out a singular space of refuge, reflection, and celebration for those who call Greensburg home. The museum kicks off its new series of contemporary art in its historic paneled rooms with Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let It All Out (2022), a multi-media installation of intimate portraits and works by other artists in conversation with Benjamin’s vision, as well as photographs throughout the museum’s galleries in direct response to collection artworks. At the outset of this project, Benjamin—who was born in Guyana and raised in Brooklyn, NY—sought to depict a largely overlooked and underrepresented community. In a short film directed by Nick Childers that plays on a loop in the small paneled room, Benjamin asks aloud: What would it be like for a Black person living out here? What is your story? What are you doing here and what keeps you here?

Break Down operates as both a living archive and manifesto for the kind of community-building that exists among small, tight-knit communities of color (if you know where to look). Benjamin’s role often feels like that of a documentarian, or as he puts it “the village narrator,” of which he points out there are very few for immigrants and African Americans. As an immigrant himself, Benjamin intrinsically understands this lack. Finding space where one can feel like they belong is a perennial search for some. There is no going back to where we came from, there is only drinking Coca-Cola in our saris or shalwar kameez or another particular instantiation of the diasporic. Benjamin captures the latter image exactly with Manjushree, Simone, and Subhasish from North Huntington—a nod to Richard Wilt’s 1947 painting Imbibers (The Coke Drinkers)—but this could also very well describe my own South Asian family who immigrated to the US in the 70s. Although it was my first time visiting Greensburg, I saw my own family in this photograph. Memories of being decked out in my most festive dupatta in Northern Virginia flooded my mind, when I’d sneak a Coke from the grown-ups during Eid celebrations. These memories are thoroughly saturated with distinct American icons commingled with both my parents’ cultures that it’s now impossible to separate them. And Benjamin has a keen sense of making this inseparability visible and worth being known.

Gavin Benjamin, Manjushree, Simone, and Subhasish, North Huntington, PA (2021)

Richard Wilt, Imbibers (The Coke Drinkers) (1947)

There is much pride and joy in Benjamin’s portraits of everyday Greensburgers, but there’s also a deep melancholy from the losses many people, especially Black and Brown people, have experienced since the COVID-19 pandemic began. This is most evident in the portrait, Ruth, Derby, PA and Ruth, Greensburg, PA (2021), a direct response to Clyde J. Singer’s Easter Morning (1948), a painting depicting a colorful flurry of ladies’ hats in the hush of morning light. At first glance, Ruth appears to be a happy moment just before or after a family gathering when both Ruths are dressed in their Sunday best. But the Mac desktop facing the ornate table seems to signify another Zoom call with their absent loved ones, while a disposable face mask drapes over the water pitcher. Behind the women hangs the Death of Elaine (1882) by Thomas Hovenden, from the Westmoreland collection, portraying an Arthurian story of unrequited love; Elaine literally dies of a broken heart, and here she is in her last moments, witnessed by King Arthur, the queen, and Lancelot, the knight who did not love her back.

Gavin Benjamin, Ruth, Derby, PA and Ruth, Greensburg, PA (2021)

Benjamin finds further inspiration from this mournful painting through his photographic response in Christine and Tricia, Greensburg, PA, and the artist (2021), where the grief of the last few years is laid bare like Elaine on her deathbed. In another scene of affliction, Benjamin has staged Christine and Tricia, and himself dressed as a plague doctor, keeping a bedside vigil. Now knowing the health inequities in the US that COVID-19 revealed, Benjamin’s work here seems to pinpoint the heartbreak that some Black and Brown citizens, and the immigrants among them, might feel toward their country, or their small town–akin to an unrequited love–and the potentially terrible circumstances of these unreturned efforts. In Childers’s film, Benjamin says, “I wanted Black people to say I’ve been there and I’ve been part of the museum.” This urgency mirrors the exhibition title, taken from Nina Simone’s song where she laments, “now my aching heart knows that we’re apart.” Heartbreak feels compounded at almost every turn.

Clyde J. Singer, Easter Morning (1948)

A counterpart to this loss is found within the Westmoreland’s paneled rooms—built circa 1750 and donated to the museum by the Scaife family in 1966—where Benjamin has envisioned a fictional Black family that has lived in the space for some 250 years. While the narrative thread feels underdeveloped at times (the artist goes little beyond taking a portrait of the whole family, a looming triptych, after Joyce Werwie Perry’s Mining America (Diptych) (2010), the impact and lived-in feeling is apparent if one lingers long enough to imagine themselves a guest in this unnamed family’s home. And Benjamin wants visitors to stay a while, as he’s devised the domestic space to be as comfortably as possible in spite of the austerity of a museum gallery. Visitors are encouraged to sit and watch Childers’s film detailing Benjamin’s process, and read up on the gallery objects in a newsprint brochure as if they’re reading the morning paper. In the grand living room are Nkisi-like sculptures by vanessa german, as well as wooden models of schooners. In one corner is an arresting Mickalene Thomas silkscreen; on an adjacent wall, a painting by Harry Roseland, a white artist known for his portraits of enslaved African Americans.

Detail of artworks on view from Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let it All Out (2021)

The elephant in the room, so to speak, remains the residue of colonial violence, yet, here it is transmuted into domestic luxury created specifically for non-white folks. The restrained taste of this fictional family’s home reminds me of the Brooklyn-born artist Ilana Babou-Harris’s Reparation Hardware (2018). Part of Babou-Harris’s installation included a video of the artist as a reparator-cum-interior designer who you might find staging the rooms of a Restoration Hardware, the preeminent furniture store of expensive and dubiously reclaimed wood: “When designing the new line, [Babou-Harris asks herself], ‘how could these newly free individuals make a space for themselves that was both free of discrimination, tasteful, and refined?’” I imagine Babou-Harris’s absurd character as the designer hired by Benjamin’s fictional family. In Break Down, however, humor is not so biting or satirical. Joy is presented sincerely and proudly across the faces of Benjamin’s subjects as they pose, imbibe, and experience life together. Perhaps one is inclined to find some kind of latent rage in this work, but what Benjamin offers is simple—community, but on a kind of IYKYK level. This exhibition is perhaps not to everyone’s taste, but it is certainly for Greensburg’s Black and Brown residents, who will recognize themselves, their friends, and loved ones in the photographs. When it hits you—as if it’s all saying, yeah, this is where we belong, we’ve actually always been here—that’s when the art really comes alive.

Gavin Benjamin: Break Down and Let It All Out is on view at Westmoreland Museum of American Art until May 12, 2023.

Shaheen Qureshi is a writer and editor. Born in Virginia to Filipino and Pakistani immigrants, her work has been published in Pidzn Club, Ewa Journal, Changes Review, Pinsapo Press, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships from Caldera Arts and MASS MoCA and holds an MFA from Bard College. She lives in Pittsburgh with her cat and dog.