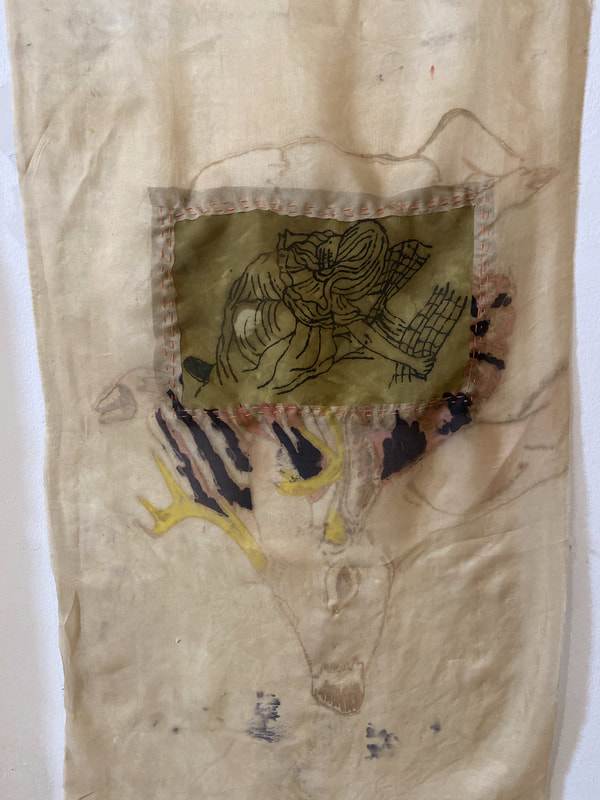

“Last Gasp (Grotto for Diana)” (2022), studio view at Bunker Projects

03/23/2022 Edited by Anna Mirzayan |

Images provided by the artist.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

Born in Chicago, based in Queens, and currently residing in Pittsburgh as a craft resident at Bunker Projects, Krystal DiFronzo is an artist and educator whose work probes the unrecognized histories of labor and bodies, particularly around female bodies and mythology. Her recent work explores gender dualities and Pittsburgh as a physical and ideological intermediary. On a Friday morning studio visit, after a brisk bike ride and a flight of creaky stairs, I met Krystal at Bunker Projects. This was our discussion.

How did you become interested in art and artmaking?

I was a really introverted kid. Until five, I was pretty rambunctious, but then there was a switch where I got very introspective, very socially awkward, and couldn’t make a lot of friends. That’s when I started to develop a deep inner life, an inner story.

As a kid, you’re not able to process all those emotions; they’re confusing and really big and hard. There was also a lack of care and friendships. I was always interested in making things, so I started drawing a lot and got into comics as a teenager. Then I realized that you can both write and draw stories, so it became a whole this is just what I have to do now.

That’s how I started off. My mother is a hairdresser, and she makes wigs. She was always doing things around the house: painting murals, tinkering with this and that… working with your hands was always encouraged.

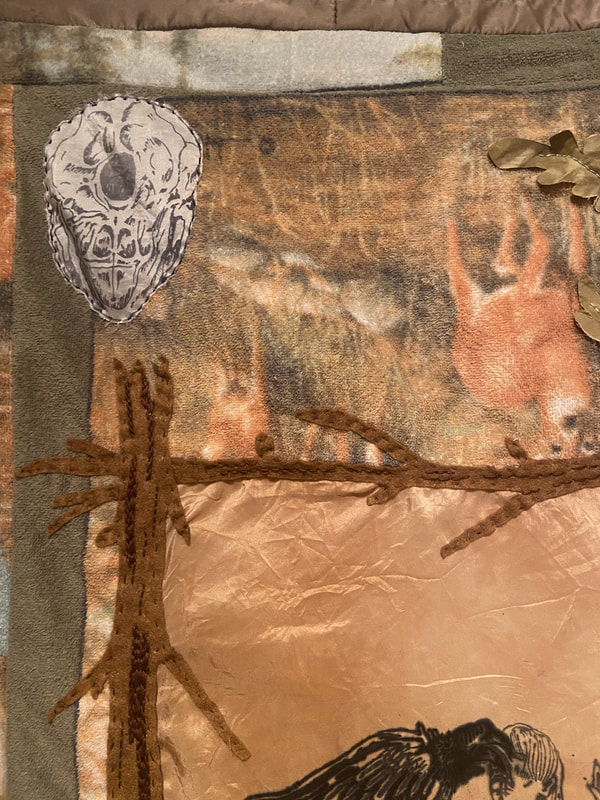

Studio details, 2022

When you’re creating art, do you view it as a form of self expression? Are you trying to put out a specific message for an audience to interpret?

My work is really ambiguous; there’s never a set idea. My work becomes a huge amalgamation of various things, usually tied into a line of research. Then, a narrative develops around that and I pull references that fit that research or that narrative to explore it a little further, or bring it in an unexpected direction… or if it really articulates the grayness of the feeling.

My work deals with a lot of issues around histories and labor. When I uncover something exciting, I’ll dive fully into it. Then when I’m doing research and I uncover something, it’s like, Oh, this is incredible! And then I just keep diving into it. As I’m thinking about how to visualize this thing, I’ll realize that it reminds me of this 1970s horror film, or a piece of literature, or my own internalized imagination, which is when moments of autobiography come into play. It’s a combination of everything, and it’s very self expressive. Sometimes it’s just, how do I piece together this huge hoard of information that I’ve gathered? How do I tangibly and visually represent those connections through material?

I’ll think about what materials will best express it. Sometimes, the material comes before the research, like how I’ve been doing a lot with natural dye on tapestries and fabrics. I’ll do a deep dive into how a certain plant is sourced, its medicinal properties, and the history of the topology around the plant. It’s a lot of chaotic, symbiotic relationships. Everything’s connected.

Artist working on “So Come and Join the Feast” (2022), in progress, at Bunker Projects

How do you compile, connect, and visualize the information you handle?

It’s different from each project. Sometimes, I have a thing and clearly know how to execute it. Then some pieces are more call and response – what do I want to compile together, what materials do I want to use. How can I pair things, put them together? I have to listen to the material and figure out how to get everybody together. It’s a language I’ve been developing for a long time, and it flows pretty easily. It’s how I speak.

“No One Could Pull Her Off the Road” (2022) in-progress view at Bunker Projects

What are you doing research on now?

I’d never been to Pittsburgh before; I’m from the Midwest. Pittsburgh feels like this weird, hybrid city of the Midwest, Appalachia, and the East Coast. It’s a really interesting space. My only visual reference of Pittsburgh was the movie The Deer Hunter. It’s a 1978, very masculine, film auteur, new American cinema movie starring Robert De Niro and Christopher Walken. It’s very problematic. It’s about the Vietnam War… There’s this group of friends that grew up together in Pittsburgh, who work in a steel factory and are all Russian immigrants. It talks about their deep friendships, but also the masculine sensitivity in how the men express love for each other. It’s physical, it’s aggressive. After the war, they come back and they’re traumatized and brutalized… how do they process these traumas when they don’t have the skill set to? Being raised male, especially in that environment, you’re not allowed the space to express that emotion.

I’ve been thinking about that film a lot because my father has similarities in his inability to cope with traumas and depression and the inability to express emotion in a productive way. Over the years, I occasionally have seen this behavior in myself as well, unfortunately, which I guess is the crux of this body of work. An attempt at understanding. Similar to De Niro’s character in the film, my father is most at peace bow hunting or fishing. Something in the focus and control… In the movie, the characters use the taking of another animals’ life as a psychic release, a way to focus on being in nature and releasing a form of anger. It contrasts with the Greek Goddess Diana, and the idea of the maternal Huntress as a provider who’s in a relationship with the animal and environment. I’ve been thinking a lot about the duality of taking a life for emotional release vs. taking a life to provide.

I’ve been working with images of deer, traps, hunting structures and camouflage and collecting things like dried plants and mushrooms on hikes, which hopefully I’ll build into sculpture. I’ve also been working with dead dough – bread dough that doesn’t have any yeast and has a lot of salt, so it doesn’t rot. It just dries out and has the appearance of baked bread. This dough has been a way to talk about nourishment… plant matter, to fire, to food. Dead dough is a code for support and comfort, but it’s dead. It’s not something you can actually eat; it’s a duality.

“The Vultures Always Want to Eat” (2022) detail view at Bunker Projects

What proportion of your work is personal expression vs. a reflection of the research you’re doing?

Lately, my work’s become more autobiographical. I’m thinking about specific traumas, and as a queer person with a complicated relationship with femininity, how to connect with the masculinity that was the root of many of these traumas. How do I piece that together? What are forms of masculinity that help me find the language for how I see myself? I don’t know. I’ve been trying to nurture and connect to that aspect of me.

I’m doing a project about my grandfather from Apulia, in Southern Italy. There’s a folk dance called the Tarantella, based on a woman who got bit by a spider. To get relief from the poisoning, she dances frantically for five days in a possessive, frantic manner, almost like she’s possessed by and becoming the spider. I’m really interested in this form of folk dance. It’s a ritual with healing ties to patron saints. At festivals, many women would go out and use being ill from the spider’s bite as a scapegoat to express all the anger and frustrations women had bottled up in their hyper-patriarchal society.

I am then connecting this ritual to something more personal; when we moved from South Florida back to the Chicago suburbs, my dad brought back the angel trumpet flowers we grew in our backyard. These are big tropical plants with long histories of being used for spiritual medicine, since they’re hallucinogenic. He brought clippings back to Chicago, and coddled them; he brought them indoors over the winter and sprayed them with oil they would get mites… he truly cared so much for these plants with patience and sensitivity he didn’t express otherwise. He had this relationship with a very toxic but beautiful flower. It’s interesting thinking about different forms of release and comfort, and how people utilize poison as a therapeutic.

“Marrow Altar” (2022), in progress

How did you get into the research historically related to the masculine and feminine, particularly regarding mythology?

A lot of the work I did in grad school depicted femme bodies because that’s the body I have; in my work, the figures were mirroring, reflecting each other. During quarantine, the being inside and being able to actually be introspective for once was complex, with the recent traumas in my family. My work sometimes has a feminist lens, since many labor histories directly impacted women, especially poor women.

I did a project on Scheele’s Green, the first version of a green dye. It was a compound of arsenic, and was put on everything. Fake flowers then, in the Victorian era, were a huge thing, and these flowers would be painted with arsenic by women and children. People were getting crazy ulcers and illnesses… then when Oscar Wilde wore the green carnation, it became a queer symbol — it just has so many connotations. Gender explorations have always been there, but it’s fluctuating a lot right now. I feel like at least it’s moving in one direction, but could end up going in the wrong direction and I don’t know where it’s going.

Alana Wu is a current student at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh, PA. She is majoring in Decision Science and Human-Computer Interaction, but loves to explore anything related to urbanism, public art, or analyzing human behavior.

Krystal DiFronzo (b.1989 Chicago, IL) is an artist and educator based in Ridgewood, Queens. They received their BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 2012 and their MFA in Painting and Printmaking from Yale School of Art in 2020. They have held solo exhibitions at Hume, Chicago; Ballroom Projects, Chicago; and Dirt Palace in Providence, RI. Their work has been shown in group exhibitions at Western Exhibitions, Chicago; Field Projects, New York; and and digitally through The Drawing Center’s Viewing Program and Perrotin Gallery.They have been an artist in residence at The Atlantic Center for the Arts and at Lafayette College’s Experimental Printmaking Institute and are currently in residence at Bunker Projects in Pittsburgh, PA as part of their Craft Fellowship program. In Summer 2022, they will exhibit a solo exhibition at Wavehill in the Bronx, NY as part of their Sunroom Project Space and participate in a two-person exhibition at Kingfish Gallery in Buffalo, NY.

Utilizing natural dye, silk painting, weaving, sculpture, drawing, and video their work seeks out histories surrounding the relationships between pharmakon, ecology, symbiosis, illness, desire, and magic. They use these histories as a framework to construct slippery narratives that weave together past bodies with personal poetics and contemporary struggles with labor, medicine, and environmental collapse.

Krystal DiFronzo’s solo show, You were born good at make die, will be on view at Bunker Projects from April 1st – May 20th, 2022.