Monadology

by Harrison Kinnane Smith

Original Publish Date: 8/19/2020

Artwork by Harrison Kinnane Smith

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

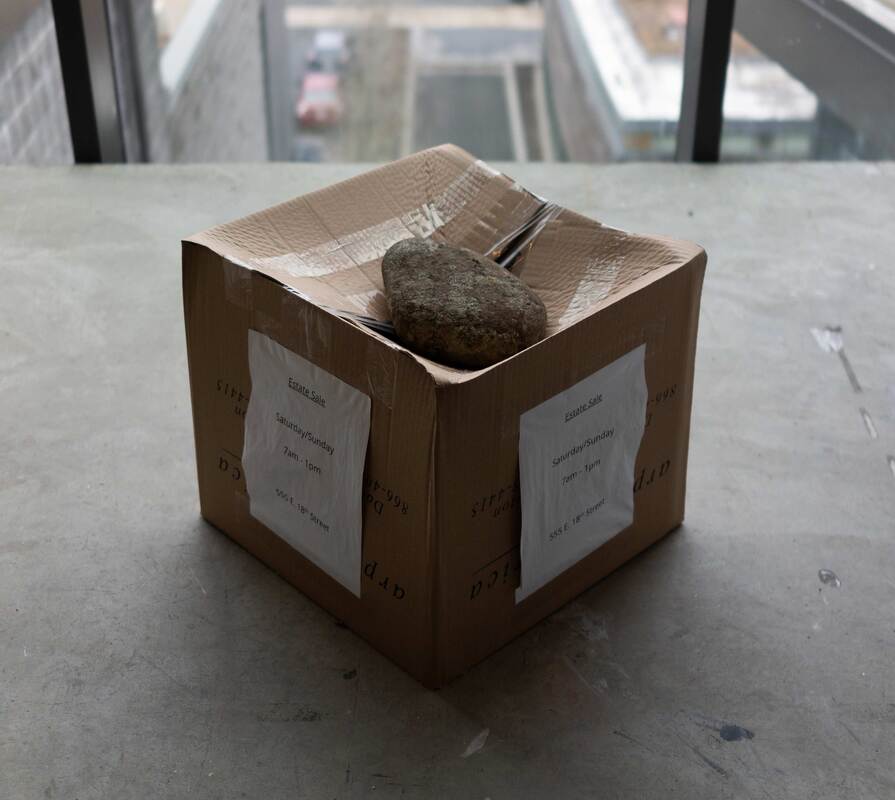

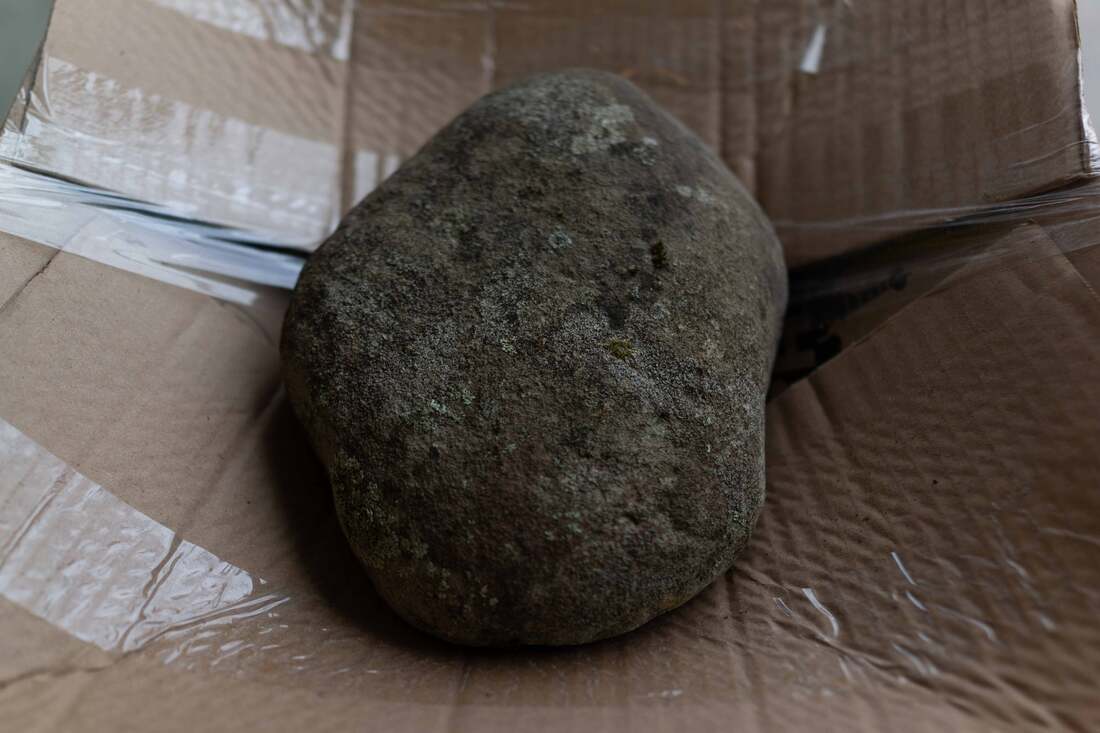

monad i (Tucson box, replica #5), 2019

In 1714, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz published The Monadology, a philosophical treatise arguing the existence of “monads,” invisible and indivisible soul-like entities essential to all matter in the universe. Each monad has a unique predetermined course of action and interaction which, he suggested, describe the ongoing development, change and interaction among monads such that from the position of a single monad, one could see the present, past, and future of the entire universe. Though The Monadology was significantly influenced by the now-outdated theological, philosophical, and scientific knowledge of its time, Leibniz’s ideas proved notably prophetic as 20th century advancements in quantum physics refined and redefined our knowledge of the physical universe.

In the mid-20th century, quantum scientists uncovered the component parts of the neutron and proton: subatomic leptons and quarks, the new indivisible ingredients of everything. Early studies of these smaller particles revealed behavior unlike anything observed before, including a phenomenon physicists have termed “quantum entanglement”: the interaction between or generation of two particles causing their essential beings to be inherently linked. Once two particles are entangled, actions on one can determine the behavior of its quantum pair across space and time — quarks in Switzerland react instantaneously to the experiences of their pairs in America, while leptons in the present determine the behavior of their quantum pairs in the past.

In seeking to explain this seeming impossibility, scientists have come to the conclusion that quantum pairs do not break the rules of physics — instead, they redefine them. At the quantum scale, particles wholly reject the Newtonian laws of the human world, existing simultaneously within and beyond the bounds of our limited spatial-temporal intuition. Furthermore, these entanglements are always happening, and because of the quantum particle’s ubiquity, the effects of entanglement are literally universal. Though we experience time through the forward-marching sliver of the “present,” quantum entanglement demonstrates that the “past,” “present” and “future” can develop simultaneously, intra-dependent upon one another. The quarks and leptons from which we are built are constantly changing and exchanging, flowing through and from our bodies to form entanglements between the particles that are us, were once us, will become us, and surround us. The contours defining limits of form are blurred as fluid subatomic particles exchange, entangle, and compress time. Just as in Leibniz’s monad, the whole of the universe becomes tangled up in the particulate matter of each object we perceive as discrete.

But when the discrete is exploded into everything, dichotomous objects become intertwined and interdependent beyond the limits of our perception — how are we to distinguish between apple and orange, water and oil, presence and void? In the face of such a fundamental disruption to our rules of existence, what happens to our understanding of being and self? Historian, physicist, and feminist scholar Karen Barad views the ontological reorientation demanded by quantum physics not as a problem, but as a gift. Colonialism, she argues, is reliant on delineating a white, masculine “self” in opposition and superposition to a manifold, antagonistic “other.” Yet quantum entanglements encourage us to embrace the world as an extension of ourselves just as the world simultaneously embraces us — a radical, destabilizing expansion of self that counters the roots of every contemporary dichotomous system of oppression. Moreover, through quantum theory we come to recognize the linkages between historic systems of oppression and those we face today.

Author and activist Alice Walker famously wrote, “All history is current.” If Leibniz is to be believed, the interactions that tie seemingly disparate events together across time are constantly occurring. When entangled electrons compress our understanding of linear time, racially-biased economic and labor legislation from the early 20th century is not solely antecedent to contemporary socio-economic disparities; instead the two exist simultaneously, inextricably linked. Though we know entanglement suggests this simultaneity is true, such radical perspectival reorientations are hard to adopt. However, knowing that inherent, quantum physical connections between these events exist can help underscore compatible notions of contemporaneity. Thus, instead of disqualifying historical perspectives, quantum theory validates the threads historians identify as tying our present condition — our present struggles — to those of the past and those yet to come.

Applying quantum phenomena as both analogy and explanation in everyday life can be tricky — my attempt to do so through Barad’s writing inevitably simplifies the more nuanced facets of both her work and quantum research, broadly. Moreover, such adaptation tends to generate more questions than answers. Yet in these questions lies the value of the pursuit, for they motivate the critical, contextualizing investigation needed to achieve a more accurate understanding of the world. To quote education scholar Tara Fenwick, sociomaterial lenses like Barad’s should not encourage us to “establish theories about why the world is the way it is…” rather, “it’s about the ‘how?’”

∙ ○ ∙

On the night of July 8th, 2019, I stumbled across an empty cardboard box lying upside down on the curb of an intersection in Tucson, Arizona. Weathered, inkjet-printed sheets of paper advertising an estate sale were taped to each of its sides. A rock rested atop its up-turned base. The impact of my encounter was immediate — the assemblage of objects seemed to resonate with a frequency I could not ignore. I was entranced by the construction, yet unable to identify why.

Upon returning to the East Coast I began compulsively reproducing the assemblage: testing various rocks and cardboard thicknesses to achieve the perfect sag, screen printing the Arizonan moving company’s logo under each taped sign, and researching fonts until I was able to exactly match the sign text (Droit Sans of Google Docs). Through these deep formal investigations, I realized that there was also a certain movement contained in the stationary, improvised signpost. The sun-baked cardboard box, responding to its dry and windy environment, wanted to move; but the rock, responding to the gravity dominating its own existence, resisted this movement and anchored the box in place. The inkjet signs affixed to the box advertised an estate sale, suggesting death — spiritual movement into the beyond. But the estate sale also entailed human movement of those left behind and the dispersion of the deceased’s objects into the lives of others, into the world at large. With this potential energy, the assemblage seemed to point outward: towards the climate and ecology of Tucson, towards the physical and emotional lives of innumerable others, and towards the lives of their things. As such, the box became a monad, containing within itself not only its own long and complex history, but the innumerable histories of the other objects with which it was inextricably tangled.

Though we may not always recognize it, these monadic ties are present in everything we see. My experience with this box in Tucson is testament to this fact, and demonstrates that all one must do in order to perceive these connections is pay attention, to be aware of the objects with which we are constantly, perpetually entangling. Such a realization would seem to confirm the perspective proposed by The Monadology, but unlike Leibniz’s proposed monad, this assemblage only communicates a blurry outline of the greater network of monads around it. These hazy relationships have palpable weight, but I can only perceive that weight, and nothing beyond. If I am unable to comprehend the networks connected to the rock and box, within which I am now forever entangled, how am I to fully understand my relationship with the assemblage? And, through that rock and box or otherwise, what relationship do I have to the people whose lives they point towards?

In habitually reproducing this box, I cannot hope to answer these questions. But the recursive practice is both mental and material. My reproductions are part of an endless chain of symbolic relationships formed by these monadic interactions, these quantum entanglements. As such, my sculptures signify the box for which they are modeled, the time in which I encountered it, and the expansive material lives of all the monads orbiting that moment on July 8th, 2019. Moreover, they are the reified investigation of this very symbolism: a quantum, monadological perspective made material; a byproduct of the experience and a marker of its impact.

This project owes much of its theoretical content to the works of Karen Barad, Hito Steyerl, and the scientists associated with London’s Royal Academy.

Glossary

Intra-dependent: A reworking of the term interdependent, which replaces the prefix inter- (between two things) for the prefix intra- (within a single thing). My use of “intra-dependent” is based on Karen Barad’s similar “intra-action”, and aims to communicate that all things within the universe can be considered part of a single entity.

Lepton: Subatomic particles that do not respond to the “strong force”, with charges of +1, 0, or -1. The most common lepton is the electron.

Monad: Defined by philosopher Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz in his book The Monadology as soul-like entities essential to all natural objects in the universe. He believed that all monads proceed along a predetermined course, and all experiences and perceptions of living entities are byproducts of the interactions of monads. Unlike atoms, Leibniz believed that monads did not combine to form matter, and that each natural object consisted of a single, unique monad.

Newtonian Physics: The physical laws describing how forces act on matter developed by Sir Isaac Newton in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. Also known as “classical mechanics”.

Ontological: Relating to ontology, the area of philosophy that attempts to understand what it means to “be.”

Particle: Infinitesimal objects such as atoms, protons, and electrons with defined properties such as spin, charge, mass, and volume. Some particles, such as protons and atoms, are composite entities made up of smaller particles. These composite particles have a volume based on the relative locations of their component parts. Indivisible particles such as quarks and leptons are referred to as “point particles” which have no volume, but concentrate properties such as charge, spin, and mass at a specific point in space.

Quantum Entanglement: The interaction of two particles that causes one of more of their properties to become linked. When particles are not entangled, the characteristics of one have no bearing on the characteristics of another. When particles are fully entangled, the state of one particle will also reveal the state of its pair.

Quantum Physics: The branch of physics exploring the nature and behavior of subatomic particles. This term is often used interchangeably with “quantum mechanics” and “quantum theory”.

Quark: Subatomic particles with fractional charges (+⅔ and -⅓) that, in varying ratios, form neutrons, protons, and other “hadron” particles.

Sources & Further Reading:

Philip Ball – Beyond Weird: Why Everything You Thought You Knew About Quantum Physics is Different. From University of Chicago Press, 2018. Available at Alphabet City. A 2018 lecture by Ball with the same title is available to stream on Youtube.

Karen Barad – Meeting The Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. From Duke University Press, 2006. Available at Alphabet City.

Michel Callon and John Law – “Agency and the Hybrid Collectif” in Mathematics, Science, and Postclassical Theory. Edited by Arkady Plotnitsky, Barbara Herrnstein Smith. From Duke University Press, 1997. Available at Alphabet City.

Tara Fenwick – “Socio material approaches Actor network theory and Karen Barad’s diffractive methodology” Interview, 2018. This lecture is available to stream on Youtube.

Hito Steyerl – “Missing People: Entanglement, Superposition, and Exhumation as Site of Human Indeterminacy.” eFlux Journal #38, Oct., 2012.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz – The Monadology. 1714.

Harrison Kinnane Smith is an artist living and working remotely from Pittsburgh, PA. He is an arts educator and project leader for the Bunker Review’s Hand-Off essay series. You can email him at harrisonccksmith@gmail.com.