Review of Nick Sardo’s ULCER by Armanis Fuentes

Installation view of Nick Sardo, I Was Never There (2023), at Bunker Projects

7/21/23

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of Stephen Joyce.

By all accounts Nick Sardo had a good May. Originally from Santa Monica, the Pittsburgh-based artist showed two paintings at the Brewhouse Arts Association Gallery in the Southside. Meanwhile his solo show ULCER opened at Bunker Projects on May 10th and was on view until June 11th.

I had a chance to see Nick Sardo’s paired paintings at Brewhouse shortly before the opening of ULCER. The paintings, each on a big hemispherical panel, spotlights a single shrouded figure whose body — if it exists under the fabric — we cannot see. Equal parts monument and painting, the seriousness of the portraits, the deliberation of the highly rendered details, are interrupted by the heavy smear of stars and drops. Those, like myself, expecting such monumental portraits from ULCER will be delightfully surprised to find a more intimate, refracted showcase of the artist’s mixed-media practice. ULCER features 11 drawings and a dozen paintings, with some sculptural flourishes in the installation of select works. Twelve oil paintings on wooden panels, all portraits of mysterious figures. Among the paintings, a pair of portraits of cloaked figures are separated by a threshold — Generational Spit I & II (2022)— both are highly rendered, with paint smeared to create a tether between them. There is another coupled set of figures among the drawings, A Need (2022) and A Want (2023) (more on them later). Last, but certainly not least: the nails. Arranged in a three by four grid, is a series of drawings, each depicting a single, whole nail from flat to point. From wall to wall, throughout ULCER we are introduced to a large cast of Sardo’s signature little guys.

Nick Sardo, Generational Spit I & II (2022)

Sardo creates hyper-individualized beings, usually seen from the chest up. Coneheads, balloonheads, invisibles, and, of course, cowled figures. There is an overwhelming masculinity to the characters, despite how ungendered they are. A number of them wear collared shirts and others are dressed like post-apocalyptic monks. Fabric is an important material within the world of Sardo’s paintings. He’s spoken about how in creating figures without bodies, fabric and ornamentation play an integral part in not just framing, but fleshing out his figures, so to speak. The materiality within Sardo’s imagery, then, becomes a corporeal language through which to communicate the absence of the body and the presence of something else in its wake.

Sardo has a knack for character-craft. They feel from the same world, and in this way familiar to each other. Despite the unsettling aura they emanate on first encounter, Sardo’s figures are easy to play with. I was with close friends when I first encountered the 11 miniature portraits that, arguably, anchor the show. My friends and I played a game of “tag yourself” with the roster.The stakes were high. I’m the invisible guy in Retain (2023) with the twinkle in his eyes. My friends saw themselves within Water Cooler Talk (2023), Tiny Amount of Intent (2023), and Third Rate Judas (2023). Selecting your avatar from a grid of characters like these reminds me of old fighting games, where your avatar communicated something about you that you couldn’t grasp yourself. Like when I chose Kitana in Mortal Kombat as a little boy and got a wave of gender euphoria I couldn’t explain for another decade… I wonder how Sardo might translate a feminized character onto one of his panels.

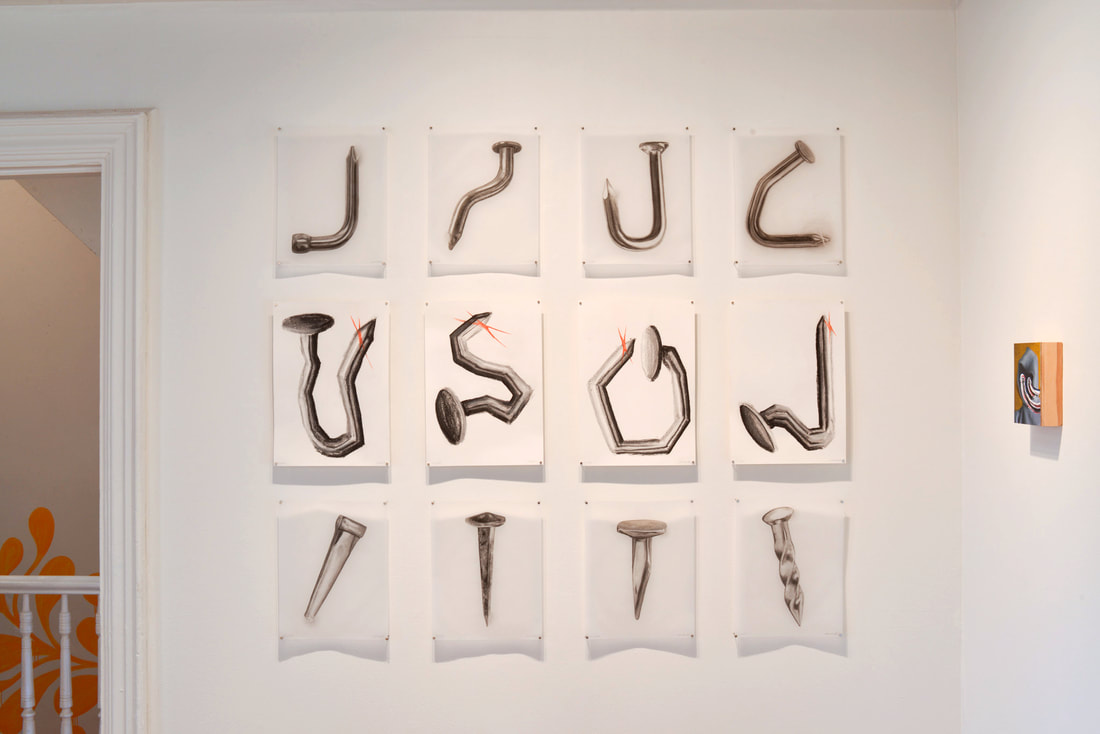

In Sardo’s hands, the icon of the nail is also fashioned into a body. In keeping with his commitment to signifying flesh through alternative materialities, each of Sardo’s Nail Studies and Nail Sketches is a full-length portrait. Though each nail remains bodiless in the sense that there is no living flesh attached to them, they are, paradoxically, the most fully-figured and fully-realized bodies in the exhibition. Some of the nails bend at sharp angles, some dance and twist, others float stiff and straight against the blank of the paper. In contrast to the other, bust-like, portraits in the room, we get to see the nails head-to-tip. They are alive despite being non-living, drawn in dynamic gestural compositions. Most of Sardo’s figures share a confounding relationship to movement. Are they heading toward or walking away? Are they moving at all? The movement of the nails, however, is all there. We as viewers can see the nail, naked, whole, in complete gesticulation. We see the impossible angles they bend at, what direction they twist about their vertical axes, where they point. In their fully-figured presentation, and baroque mannerisms, Sardo’s nails exhibit an explicitly energic articulation of the body.

Installation view of UCLER (2023), at Bunker Projects

Nick Sardo, Nail Studies, One through Eight and Nail Sketches, One through Four, Installation view at Bunker Projects

Nowhere in ULCER is Sardo’s engagement with divine portraiture more salient than in his twin charcoal portraits, titled A Need (2022) and A Want (2023). Both works are gestural, urgent. In A Want, the figure appears like a sharp flash of lighting, with a widely jagged silhouette and eyes — pure-energy, black-hot. Technically and thematically, A Need is sharper than its counterpart. An accumulation of smaller, staccato-like gestures, the figure stares blankly through its two black-bead eyes. Its realistically rendered set of lips sit in a disappointed pout. A Need exudes a darkly divine energy. Sardo himself states that Byzantine-era religious portraiture and aesthetics influence his works. In A Need and A Want, Sardo’s commitment to depicting beings beyond comprehension is made clear. In these drawings, the artist engages a long history of “picturing God,” of visualizing the unimaginable. Typical of Sardo’s characters, the characters in A Need and A Want possess a clear form, but the notion of a body is done away with. Here we return to an old paradox within the history of religious imagery: aniconism. What does god look like? Can, and should, we mediate God through imagery? How do we picture a bodiless God?

Here I would like to turn back to the title of the show: ULCER – an open sore that surfaces when an injury improperly heals. Ulcers present a way to think not only about what is at stake in Sardo’s work, but an ulcer is also a potent metaphor for a fundamental challenge in drawing and painting: how does one resolve the tension between the flat surface and the imagined depths? What discomfort arises when the subcutaneous dimension breaks the surface for all to see? According to Sardo his characters are “never uncomfortable in their environment,” perhaps because they are torn by the polarities of their position. Anxiously affixed, the characters rub between visible and unfathomable, figured and bodiless, sanctity and fiendishness, whimsical and overwrought. In this threshold, Sardo’s silent figures sing.

Installation view of Nick Sardo, A Want (2023) and A Need (2022), at Bunker Projects

Armanis Fuentes is an artist and writer based in Pittsburgh. They are a member of the artist collective Hotbed.