12/6/2022

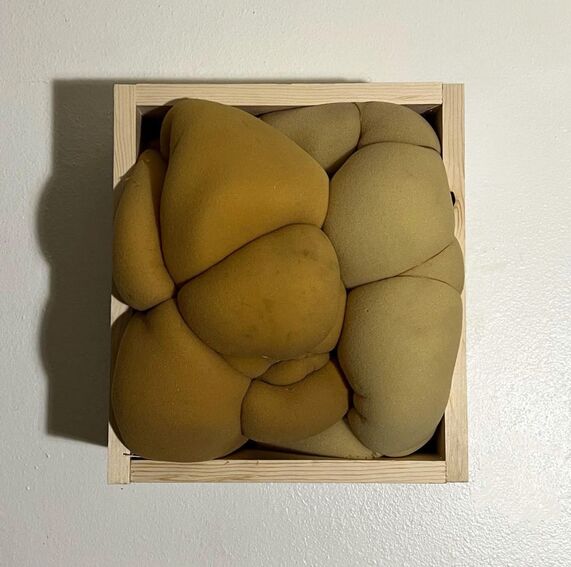

Katie Rauth, Well laden with things of complacence (detail, 2022). Courtesy of Anna Mirzayan.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

Take your analogies too far: if the body is a canvas, then the fat body is a daunting canvas. It’s a canvas whose scale provides so much room to work that the ability to choose gestures discerningly is crucial. The opportunities to lose focus, to make a big nothing are everywhere. This is not true of literal fat bodies, of course, but perhaps the conflation of literal bodies with bodies of wood, light, paint, foam, and sugar can help us understand Soma Grossa, curated by Anna Mirzayan for Brew House Gallery.

Decades of ceaseless blather about body size, healthy eating, self-discipline, and “feeling good in your skin” have made us all perfectly tiresome neurotics. I don’t know anyone who doesn’t feel burdened by their weight, high or low. So many of us have “fitness goals” which could only be achieved if Adobe Creative Cloud rolled out a Metabolism app. (Or would that be by Meta? No matter.) Our waters run alkaline; our fields, organic; our serotonin, away. And while it is true that fat people are penalized — systematically and cruelly — for not being neurotic enough, or not being neurotic in the right way, we have to come to grips with the fact that none of us are doing very well. We’re all miserable in our skin.

Néstor Daniel Pérez-Molière, Worth (still, 2021). Courtesy of the artist.

Soma Grossa doesn’t lie to us. There are no hackneyed celebrations of fatness. None of the works on display claim to have somehow unilaterally transcended the societal pressure to be thin, to have found a way to be unabashedly fat in American culture. Instead, several artists mobilize the precise ways that they experience that pressure. For instance, Néstor Daniel Pérez-Molière’s video works offer an anxious dreamscape in triptych. On the far left, an extreme close shot shows footage of muscled, tanned men projected literally onto Pérez-Molière’s skin. Interrupted by strands of hair, the texture becomes reminiscent of light entering through the blood vessels in the eyelid. On the far right is a loop of Pérez-Molière rustling in bed, trying to get comfortable. Sounds of heavy breathing and scratching sheets dominate. In the middle, a close-up video shows Pérez-Molière from the middle of his thigh to the bottom of his rib cage, trying to pull up snug pants. He’s tugging on zippers, waistbands, belt loops. It succinctly evokes a psychic homunculus — the experience of the body magnifying and minimizing to situate our anxiety. When our pants don’t fit, we’re only the place where they don’t fit. Pérez-Molière’s discomforts are somewhat universal, but in the context of Soma Grossa, we can ask what is specific to the fat experience of being a body in conversation with desire and matter.

Zoë Schneider, Swimming in Nostalgia of Imaginary Pies (studio detail, 2020). Courtesy of the artist.

While Pérez-Molière’s work, in this context, asks about the interface of fat and feeling, Zoë Schneider and Katie Rauth pursue the connection between fatness and the symbolic. Schneider’s freakishly bright Swimming in the Nostalgia of Imaginary Pies series of sculptures taps into a bit of millennial nostalgia as well as the troubled presumption that fat people equal food. Foam hamburger buns congeal together with bright ‘icing,’ drawn directly from the food fight scene in Hook. What does it mean for a fat artist to depict food? We are all constituted by food, require it to exist. Perhaps fatness, in American parlance, is a relationship to food wherein food comes to be a stand-in for the fat person. Schneider boldly displays not only her connection to food, but its inextricable link to pop culture and childhood memory. Jesse Egner’s photographs also invoke nostalgia, with ties to mermaids, Lite Brites, and doll’s heads. A millennial consumer jargon seems more key to the images than fatness — perhaps prompting us to consider what it means for that relationship to go uncommented in a work of art.

Katie Rauth’s sculpture, Well laden with things of complacence (2022) works along a similar line. A dining table breaks two legs and falls on a chair, shattering it. Sugar decor tumbles and cracks. Fresh fruit sits exposed. It’s something like a still life in ruin. Again food emerges, and this time there is the implication that the food is an impossibly weighty force, crushing. Rauth’s piece does not invoke gravity, though. If something has cracked the table, it is invisible. There isn’t enough food or sugar work decor to do the job. Is Rauth telling us how little food is required to ruin everything? Or how impossibly heavy a small amount of food can feel? Perhaps, but the arrangement of parts makes it difficult to sustain this reading. The arrangement does not show a clear movement of force, or any sign that the weighted symbol has impact other than collapsing the table and chair. Together, these four artists offer varied possibilities on the matter of fat symbolism.

Amanda Kleinhans, Fitting XIV (studio detail, 2022). Courtesy of the artist.

Amanda Kleinhans, Elisha Cox, and Sophie Pearson focus less on the use of fat symbolism and instead explore aesthetic possibilities of expressing a fat perspective. Or, put another way: they ask how being fat shapes one’s use of materials. Kleinhans’ small wall-mounted sculptures confine rounds of foam within plywood frames. Within the frames, the foam is further constrained by lines of sinew. Like Pérez-Molière’s contribution, Kleinhans’ offers a clear visual of excess and the pressures to which it is subjected. In Kleinhans’ work, the key tension is that of sinew — of a link which binds together the body or bodies. Elisha Cox’s sculpture, Bulge (2022), allows the tension to overflow, as flour seeps from a fabric form suspended from the ceiling and onto the floor below. Imagining Bulge in the gallery for the duration of Soma Grossa, the phrase “weight loss” comes to mind. If Kleinhaus introduces the tension we seek to ignore (the ‘ruthless calculus’ of anti-fat bias which Soma Grossa highlights), Cox releases that tension and — leaving us spent — makes us reckon with what our fantasies just might be. Along with Kleinhaus and Cox, Ren Buchness demonstrates fullness in their mixed-media works. Surfaces of bodies cracking from the outward push of inner being. Here, Buchness breaks with the decidedly non-idealist approaches of the other artists in Soma Grossa. In Buchness’ images, objects (including but not limited to food) array the close-framed bodies as ornament or offering. If food stands in for fatness in these works, it is a closed correlation — one which makes it difficult to explore the dimension of either. The ritualistic tones of Buchness’ work brings ideas of nature and future into an exhibit which otherwise does not engage them.

Sophie Pearson’s canvases also engage the materiality of fatness as an aesthetic concern. Pearson, I would argue, doesn’t just paint portraits as a fat artist, but in fact paints fat. Pearson differentiates tone and color across expanses of flesh, leans into depictions of gravity and the pull of bulge. Pearsons’ use of color neglects no area of the body. Pearson’s eye is unhurried. It is an expression of fatness as not only a social condition, but a material reality which brings with it the possibility (and challenge) of modulating more space. Danielle Attoe’s jewelry invokes this modulation as well. Jewelry adorns and, in the era of the Glowforge acrylic Etsy bonanza, can make a didactic statement. Showing fat women from a plurality of angles, along curves reminiscent of papasan chairs, tire swings, or mirrors, Attoe’s jewelry presents the possibility of wearing fatness, of modulating the space of the body — whatever its dimensions — to say something about fatness.

Elisha Cox, Bulge (detail, 2022). Courtesy of Anna Mirzayan.

With space, weight, and symbolism at play, Ashley Ramos’ painting Ascension (2022) finds a clear home in Soma Grossa. Towards the center of the canvas, a woman stands nude with one foot on a skull. She holds a mask above her head. Something like wings, or a sheet, or petals unfurls behind her — not quite attached to her body, not quite indifferent to it. The rest of the canvas is perfectly black. Her right thigh, stepping forward, holds up pulses of flesh from between her breast and her hip. The thigh scintillates with lavender and chartreuse. She pivots on that thigh, pushing down onto the skull. But what does she press it against? Nothing. Ramos evokes the most cowardly argument used to devalue fat people — their supposed proximity to death. Ramos’ figure steps on death, but cannot crush it. And who among us can? Still, she effectively pushes against it to move herself. That is living.

Soma Grossa is on display at Brew House Gallery through January 14, 2023.

Dani Lamorte

is a Pittsburgh-based artist. More: www.danilamorte.com