Entry view of An Angle Grinder Grinds in the Background (2023) at Coco Hunday

Culturesmith: Alfredo Ramírez Raymond at Coco Hunday

Review by Brandon Sward

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of Coco Hunday.

When I was living outside of Quito, I saw a scene from the Middle Ages. At a street market in the city, two men were shaping a knife with a blowtorch fueled by a nearby propane tank, to which it was connected by a black rubber hose. The metal glowed a color I’d only ever seen on a screen, in films or television programs set in another time and place. Once the reddish-orange had nearly spread across the entirety of the surface, one would move it to a nearby anvil. At the same time, the other quickly went to work on it with a small hammer—one of the two adjusted slightly to expose another angle with each stroke. With each stroke, one of the two adjusted themselves slightly to expose another angle. Upon the conclusion of this subtle dance, the one holding the object would briefly submerge it in a large bucket of water close to his feet, producing a soft fizzle and a small cloud of steam. When it cleared the water, the blade was again subjected to the small blue flame of the blowtorch, beginning the process all over again. These two were engaged in forging, a process whose history spans many centuries.

As my fascination betrays, these sorts of practices are ostensibly being made obsolete by recent technological innovations and changes in consumption, leading to a loss of knowledge that has been passed down over time. The truth of the matter, however, is that culture, like metal, is neither created nor destroyed—it merely changes form. Indeed, the prevalence of Smith and its equivalent in other languages as a common occupational surname attests to how widespread it once was. It is precisely this extinction of a lifeway that Alfredo Ramírez Raymond takes up in his An Angle Grinder Grinds in the Background (May 6–December 2, 2023) at Coco Hunday in Tampa. This exhibition centers on a series of defunct machines that had formed the core of his family’s multi-generational metalworking business, which shuttered during the early 2000s after over half a century in operation. Upon their restoration, Ramírez Raymond invited fellow artists Rafaela Armendaris Parducci, Lucas Neira, and Karin Iturralde to collaborate informally on a series of pieces produced with this born-again equipment.

Installation view of An Angle Grinder Grinds in the Background (2023) at Coco Hunday

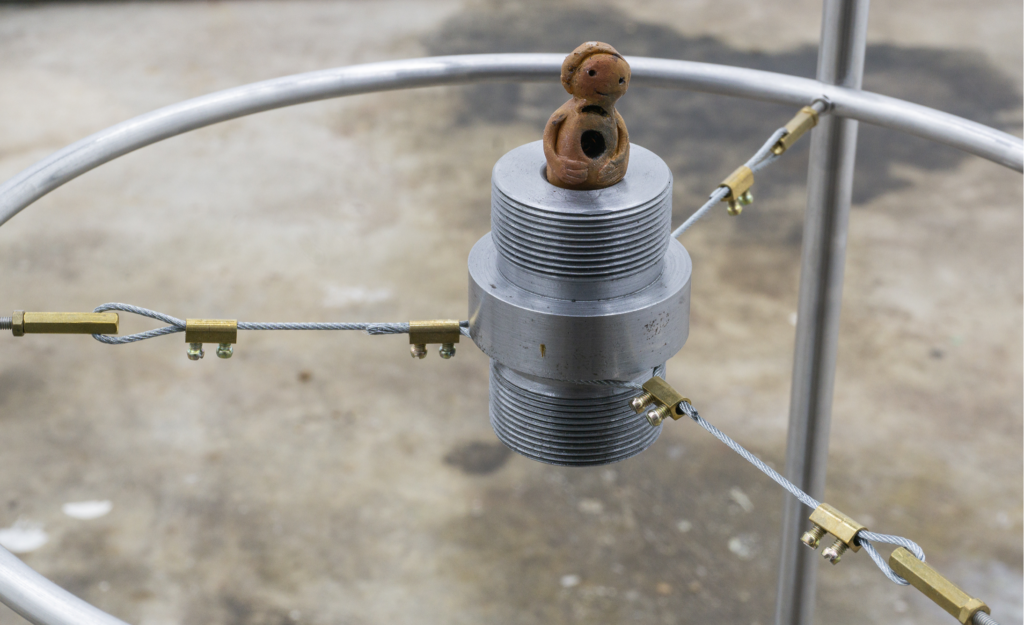

Many of the works on display reflect this passage of time. In No somos tan ancestrales (“We are not that ancestral”), Ramírez Raymond and Armendaris Parducci combine rods, cables, and hardware with replicas of artifacts from the Chorrera culture discovered by Armendaris Parducci’s aunt, Resfa Parducci. A civilization that flourished between 1300 and 300 BCE, the Chorrera were the earliest known metalworkers of pre-Columbian Ecuador, a practice which as we have seen continues to the present day. On a much more recent timeline, El acero en reposo se siente friecito (“Resting steel feels cold-ish”) incorporates a seven-year-old workshop shirt belonging to Ramírez Raymond, attesting to the length of his engagement with the medium. Though inorganic, metals themselves have their own experience of time, as evidenced in Para los papás que nos llevaban al karting (“For the fathers who used to take us to see kart races”), wherein a used copper welding plate is suspended on a steel plate anchored to the gallery’s walls with four tightly stretched ratchet straps.

Close-up of Alfredo Ramírez Raymond, Rafaela Armendaris Parducci, No somos tan ancestrales (We are not that ancestral), (2022)

For all their concern with time, many of the pieces also evoke a sense of space. Several, for example, are made of coins, one of the most familiar forms metal takes in everyday life. Notably, these coins come from both Ecuador and the US. While the country adopted the US dollar as its legal tender in 2000 to prevent the collapse of its monetary system after defaulting on a currency bond to a private bank, the Central Bank of Ecuador still mints its own centavo coins, which are identical in size and value to their US cent counterparts, but relies on the US for its banknotes. We might understand Ecuador’s decision to produce its own coinage as an attempt to assert its independence even as it depends on powerful extra-state actors like the US and World Bank. In a spindly figure like Maria Fierrito, the artists have literalized the deep connection between the US and Ecuador by producing a nickel and copper alloy from each of the country’s half-dollars.

Alfredo Ramírez Raymond, Karin Iturralde, Maria Fierrito, (2023)

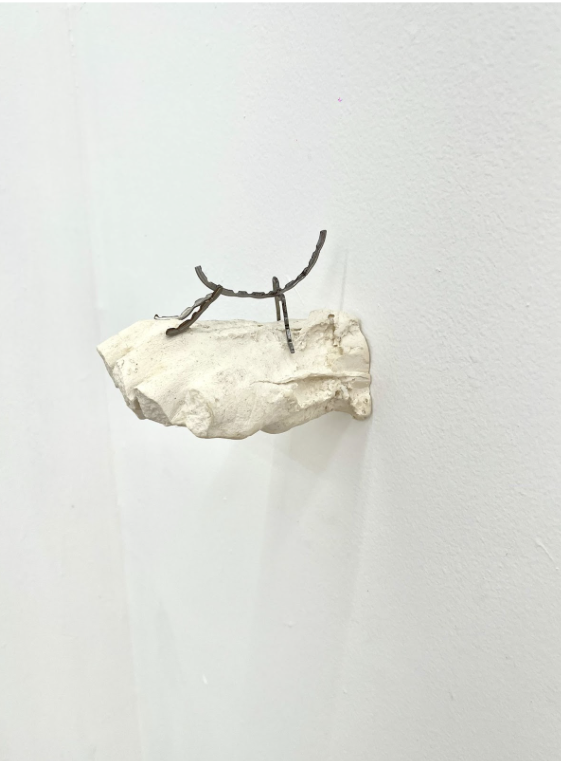

These US–Ecuador economic exchanges. Included are two rings and a rearview mirror decoration that each broadly references consumer culture.. Yet, the rings are bulky and strangely shaped in ways that might easily pose problems for a wearer—perhaps why they’re displayed on individual plaster fingers protruding from the wall rather than a full hand. Materially, the rings and rearview mirror combine US coins with screws, wires, rods, and other forms of hardware, thus bringing together the symbolic and structural potential of metal, as money and as a tool respectively. Though metal is often understood to be hard and unyielding, An Angle Grinder Grinds in the Background reveals its adaptable and multifaceted nature, and in the process, gestures toward the similarly complex and ever-changing relationship between not only the US and Ecuador but also the attitude of the US toward all its southern neighbors, from the interventionism of Operation Condor to the isolationism of the current migrant crisis.

I often say of metal that, unlike wood, it can bend, and unlike clay, it stays where you bend it. This plasticity and strength has allowed the material to turn the wheels of history. Without it, there would be no airplanes, skyscrapers, computers, or telephones. It has become impossible to imagine life without it. But, like all resources, the supply of metal is finite. And, for better or worse, our future is bound up with metals as well. From lithium to cobalt, metallic minerals will need to be mined at a huge scale to meet the growing demand for batteries, especially in the electric cars that politicians continue to promise will soon outnumber their gas-guzzling predecessors. And it is precisely the Global South where the majority of these precious stores lie. Through their interventions, Ramírez Raymond and his collaborators demonstrate how, through care, metal can be recycled and refashioned into something new. The question, however, is whether these transformations can occur at the pace needed to bring ourselves into balance with the materials surrounding us.

An Angle Grinder Grinds in the Background is on view at Coco Hunday in Tampa, Florida, through December 2nd, 2023.

Brandon Sward is an artist, writer, and Editorial Associate at the Los Angeles Review of Books. His words can be read in The Chicago Reader, The Point, High Country News, and dozens of other local, national, and international publications. He is also the author of the Substack News from Nowhere. He has been nominated for several literary prizes, including the Pushcart, and has attended many residencies, among them Yaddo, Byrdcliffe, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts.