11/9/2022 Photos courtesy of here gallery.

Jamie Earnest, Cowardice Masquerading as Reason (silence) (2022), installation view. Photo courtesy of here gallery.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

In Jamie Earnest’s solo exhibition, Good Mourning, at here gallery, she considers what it means to mourn the nostalgia for a dream of the South that lived up to its reputation for hospitality. Earnest, who grew up in rural Alabama, makes work that contends the everlasting societal impact of the South’s transgressions. Earnest’s paintings are confrontational, yet gentle,tenderly orienting our gaze toward a beauty that might otherwise be overlooked.

The works show a first person perspective but the orientation is uncertain, as if we’re looking in multiple directions simultaneously. Out of joint, we find ourselves at the collision of broken pasts and futures not yet assembled. In the span of seven paintings, Earnest places us at the threshold of light and dark to facilitate the reconciliation between that which is living, that which is dying, and that which is yet to be. To make sense of an immortal past that threatens to leave the present lifeless.

Jamie Earnest, Midnight Meeting (specter) (2022).

There are factions of the South that are invested in hiding its past atrocities and silencing any echo that might draw attention to the latter. Even books that merely acknowledge their history are dismissed as propaganda, and disappeared from southern libraries and schools; in 2021 a school board in York, Pennsylvania banned Hidden Figures, a book about three Black women who fought sexism and racism to help America win the Space Race in the 1960s. In that same year, Texas State Representative Matt Krause called for the removal of 850 books that either celebrate diversity or confront oppressive systems, citing the potential guilt some students might feel as his reason. There are those that would have us believe there is nothing to hide. They would have us believe that the United States warred with itself and came out unscathed– as if America, especially the South, isn’t losing a tug of war with its past, as it changes its mind on what human rights are. But there are those of us who don’t have the privilege of disbelief.

Mississippi-born writer William Faulkner wrote extensively about the South’s sins in explicit detail, in an effort to reflect the American South to anyone who would look in his work’s direction. In Absalom, Absalom! he considers how ghosts of the South’s past haunt subsequent generations, while exploring who’s responsible for rectifying that past, and how avoidance can lead to destruction. Faulkner has said that the South’s curse is slavery and that it was up to the South to work it out. In 1956 Faulkner urged civil rights activists to “go slow” in their attempts at liberation, implying the South wasn’t ready but could eventually warm up to ideas such as desegregation in due time. To which James Baldwin responded, making it clear that the time Faulkner asks for doesn’t exist.

The trick of the South, at least of those in power interested in avoiding its past, isn’t to just make the South’s ghosts disappear. The trick also relies on getting people not to believe in ghosts, to convince them that anything that resembles one is an actor in a costume pretending to be a ghost to monetize the fear they hope to manufacture.

I’m not talking about men running around in white sheets, although the same could be said for them. I’m instead talking about Hauntology as described by Algerian-French philosopher Jacques Derrida. Hauntology suggests that what happens in the past remains present in our todays and our tomorrows, and that what will happen in the future already haunts our present. We must learn to acknowledge, and live, among specters. I’m not interested in using this moment to focus on the South’s evils or the ghosts it employs. William Faulkner, Toni Morrison, Scarface and The Geto Boys, among others, have already done so, brilliantly.

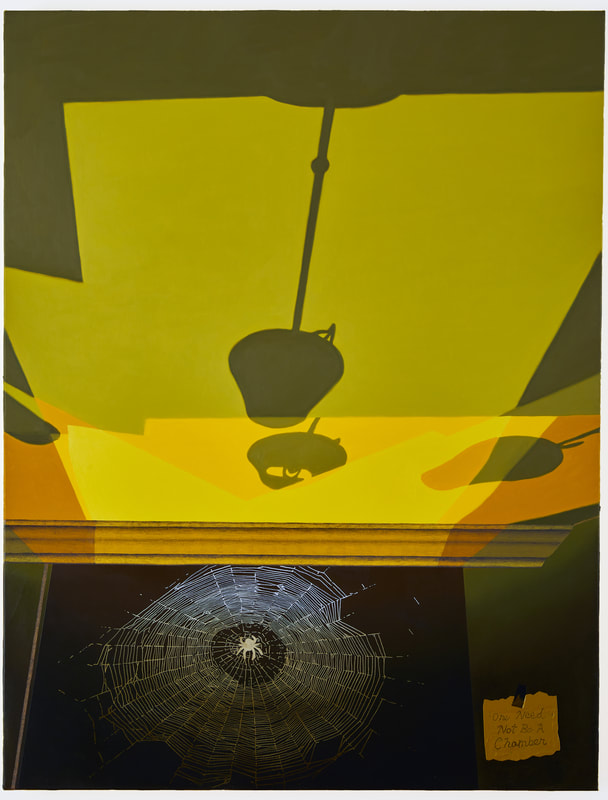

Jamie Earnest, Ethic of Neighborliness (2022).

In Ethic of Neighborliness (2022) Earnest, pushes back against those who exhibit performative congeniality, and are more concerned with the perception of friendship than their neighbor’s wellbeing. People whose allegiance is to the state, rather than their neighbors. To quote Baldwin in his response to Faulkner’s hesitancy to desegregate: “They have never seriously considered that their social structure was mad. They have insisted, on the contrary, that everyone who criticized it was mad.”

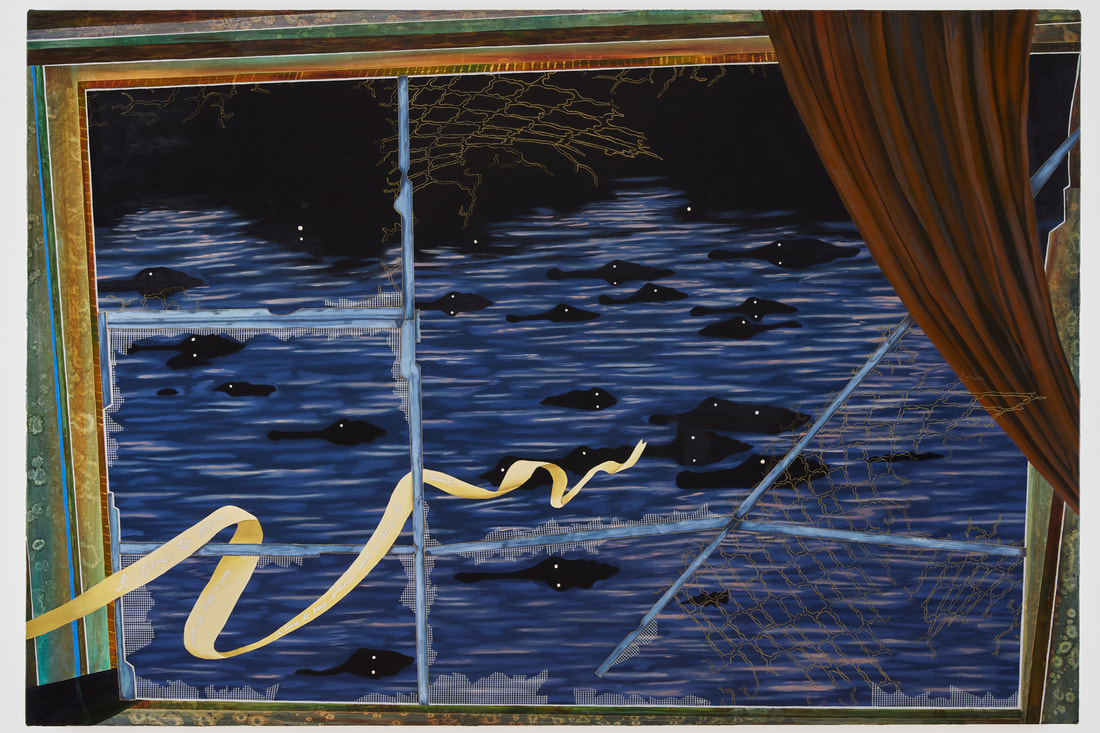

In Cowardice Masquerading as Reason (silence) (2022), Earnest depicts the interior view of a broken domestic window overlooking a river where a congregation of alligators camouflage themselves in the current, almost invisible were it not for their eyes refracting the moon’s light. The window’s pane is shattered, and the broken right two-thirds of its grilles desperately hang on to the left portion that miraculously remains intact. Only a side swoop of drapery on the right is unharmed. A ribbon that reads “a time to tear and a time to sew; a time to keep silence and a time to speak” is reluctantly being pulled out of its home by an intimidating wind. The ribbon’s attempt to wrap itself around one of the grilles is futile, and it seems as if whatever it was that broke through the window is determined to not leave it behind. However, despite the wreckage, the scene feels optimistic.

Earnest considers how fear prevents people from speaking against evil. She highlights a bible verse (Ecclesiastes 3:7) that, depending on who wields it, could be used as a shield to protect their silence, or a sword to defend their speech. The south has a history of terrorizing those who attempt to hold it accountable for its hate. Sometimes the cost of naming and condemning this hate is life itself. Lives have been taken as a result of the right words traveling from the wrong mouth to the right ears, but I don’t wish to invoke martyrdom here.

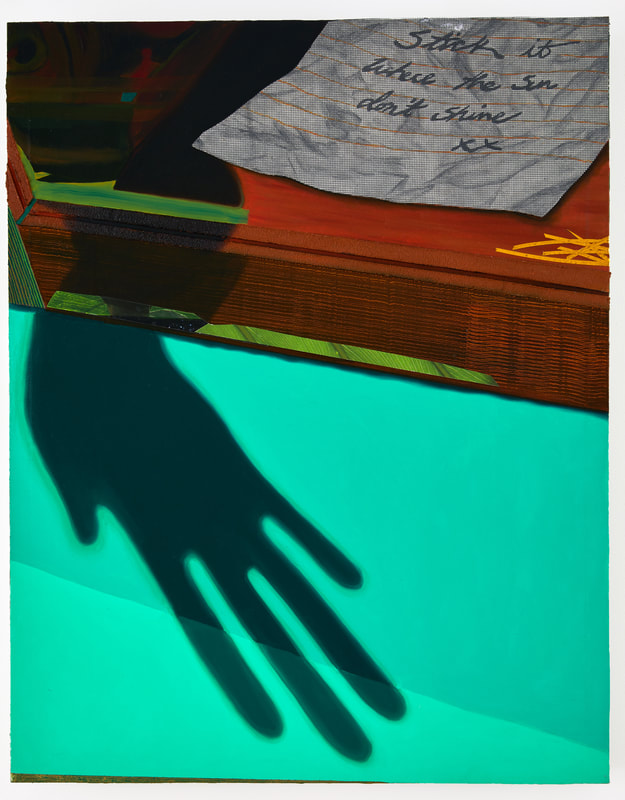

Jamie Earnest, The Great Leveler (2022).

I don’t want to dismiss the threat of literal death at the hands of the South, but I’m instead referring to the loss of a life we once knew. I’m talking about the killing of systems, myths, and relationships. I’m talking about the killing of that which the undead has made alive. Dismantling the machinery that ancient ghosts have newly built to torture current and future generations. I’m talking about when the grim reaper pulls up for us but it doesn’t pull up on us. Instead, it walks with us in its shadow, swinging its scythe to clear a path for our harvest.

In the outdoor scene of The Great Leveler (2022), we’re positioned at the bottom of a flight of stone stairs, covered in a spotless, red, glimmering, silk-like fabric that looks almost too nice to step on. The fabric blankets the stairs as well as a portion of the tall, unruly grass that remains unbothered on either side. The stairs’ width extends beyond the frame of the painting, yet the fabric is only as wide as a doorway, or a red carpet runner, inviting us to our ascent toward an uncertain horizon. A small pendulum clock at the foot of the stairs reminds us that time is of the essence. Two scythes lean across each other at the top of the stairs, not in a way that’s menacing, but like a door protecting what lies beyond.

Jamie Earnest, Between Omens (2022).

It’s in this moment where we make friends with death and learn to tend to its garden, and do the rigorous work of mourning. A labor that brings us to our knees, coloring them grateful with memories of where the forgiving soil broke our collapse. A labor that also summons our hands to the ground, towing our body’s crawl, putting more miles on our palms than on our feet. So much so, gloves are as necessary as shoes. A labor that drains enough tears to sustain this garden in a drought. In this rural cemetery where we house the undead, we also produce life. Here, where we name our specters, tuck them into earth, maintain their resting place, and pray they don’t disrupt our lives too much. We pray that if we continue to take care of them, they might not bother the loved ones we promised to protect. We pray that our labor is not in vain. We pray our gardens bloom flowers that comfort those who receive them. Flowers that express what words can’t. Enchanted flowers whose last picked pedal is always “loves me” and never “loves me not.” We pray we have enough flowers to give bouquets to those whom we love that are both living and dead, with enough left over for those we’ve yet to love, and those we’ve yet to lose. We pray our flowers bloom beautiful enough for butterflies to dance with. Black butterflies, like those rendered in Earnest’s Between Omens (2022), that usher us over the threshold of death, toward the light, toward transformation.

The journey of mourning is often communal. And there is perhaps no bigger example of collective American mourning than Memorial Day. In 1865, before it was an official holiday, a group of newly emancipated Black folks in Charleston, South Carolina, organized a parade to give over 260 dead Union soldiers a proper funeral after the Civil War’s end. Over 10,000 attended to not only honor the ghosts of those who died fighting the South, but also to process the ghost of slavery. While Southern hospitality as we know it may be a myth, it was southerners who taught us how to welcome our specters with open arms and flowers. Attendants left so many flowers on the graves that the land was invisible. When the holiday was officially established nationally in 1868, its then date of observance (May 30) was determined because by then flowers would be in bloom across the country.

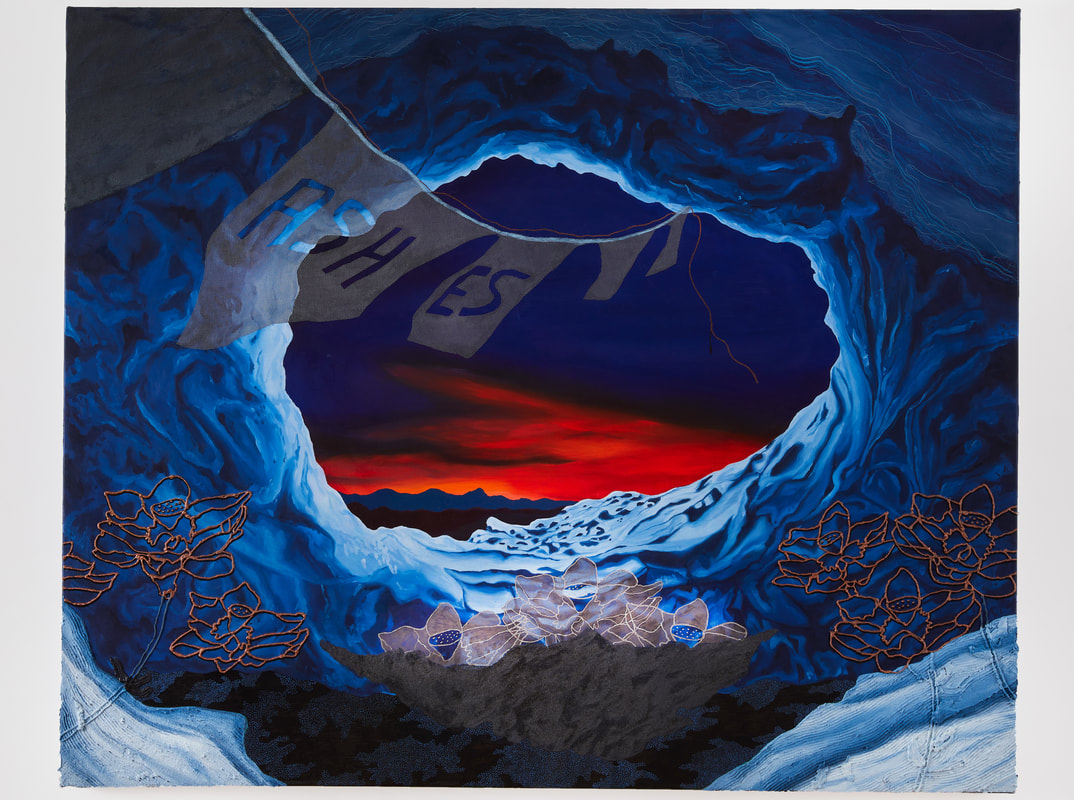

In Honor the Darkness / Trust the Light / Grow through the Mud (2022), Earnest highlights the transcendence of the lotus flower, which is known for its ability to grow in muddy water and emerge without a stain. The lotus flower is also capable of self-pollination, and when its seeds are dispersed, the current carries its descendants to a new location, where they’ll repeat the cycle. It has been said that lotus seeds can remain dormant for upwards of 1000 years before blooming. It reminds us that the distance of space and time isn’t always an accurate measure of how far removed we are from our past. More importantly, it demonstrates that it is possible to rise from any dirt, clean.

Jamie Earnest, Honor the Darkness / Trust the Light / Grow through the Mud (

2022).

My cousins from Louisiana, where my maternal family tree is rooted, would often come to stay with us at our home in Ohio. Sometimes temporarily, sometimes permanently. For them, the small town quiet of Mansfield was refuge from the threats of 1990s New Orleans. Louisiana currently has the highest murder rate in the country, a spot it has occupied a dozen times since 1993. Yet New Orleans is also a city where funerals joyously parade down streets led by the blare of brass bands, and the movement of dancers, welcoming any and all bystanders to join the celebration of life. The funeral second line never lets us forget the power of communal mourning.It’s a miracle that New Orleans, a city surrounded by such grief, is able to mine so much joy.

When my cousin from New Orleans moved into my bedroom, he brought with him a CD case full of seemingly every Cash Money and No Limit release, including Master P’s Ghetto D. The first single from Ghetto D, “I Miss My Homies,” is an exercise in mourning in which Master P, Pimp C, and Silkk the Shocker eulogize friends who have died or are in prison. It’s a song I heard so many times in our shared room, I still know the words, despite not listening to it since the 90s. At 9 years old, it wasn’t a song I related to, but it’s safe to say it meant something to my cousin who is 10 years my senior, fresh out of a place where the odds of survival for boys his age weren’t high. When my family from down south would talk about getting another year older, they would say “make,” as in “he made 21” never “he turned 21.” As if they intended to distinguish from the passive “turn” where you age by accident, simply by being present on Earth as it takes you for a ride, while it turns around the sun. To “make” another year, says that it wasn’t guaranteed and that you had to have a hand in forcing its arrival. It acknowledges your work and underlines the accomplishment.

It was unclear to me then, that “I Miss My Homies” was for him, the work of mourning. A kid who I thought was a man, I now realize was a kid 1000 miles away from the people he loved most, trying to make the most out of a new situation. What wasn’t clear to me then, that became clear to me later, was that the same past that haunted him, also haunted me. I don’t mean haunt in the spooky sense– I mean haunt in that his past was present. The difference for us was perspective. I didn’t see all of his past, or the path that brought him to me. I didn’t see the whole picture, only what was carefully revealed to me, and I knew behind his perspective was a darkness I didn’t need context for. Like the paintings, the background was obscure but I was nudged toward a light. The presence of that which haunted him, and many of my southern cousins, blocked my entry to a path I had no business on. I never saw my cousin’s hands dirty. As the judge sentenced him to 20 years, he praised his intelligence, and expressed sorrow for the future he lost. I’m still mourning.

The work of mourning considers not only our present, and our future, but also the futures of others, especially people we care about. In our mourning we learn what haunts us and work toward understanding the magic of perspective. The past will remain, and there’s nothing we can do to change it, but we can change the way we perceive it. Earnest figures out this magic and uses it, not to disappear history, but to bring the future to us. A sleight of hand that reduces the field of vision, so that more light is seen than dark. This, of course, doesn’t actually alter the path we have to traverse, but it might make our walkway bearable.

Sean Beauford is an art enthusiast and museum worker. He can be reached at seanbeauford@gmail.com.

Good Mourning was on view at here gallery from November 8, 2022 through October 5, 2022.