7/21/23

Installation view of Centa Schumacher, It is Longing to be Seen (2023), at Bunker Projects

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of Stephen Joyce.

I’ve written this down elsewhere:

I’m sitting in the elongated shadow of a memorial statue for a war that was fought before my grandparents were born. Across the street, a man is standing between parked cars and staring at me. “Take a picture. It’ll last longer,” I think. He crosses and asks to take my picture. It’s for his photography class. We begin to talk about cameras and our dreams of what they might make for us. We both complain that today’s digital cameras see too much, see too clearly. The shadow moves and my forearm burns in the sun.

It is Longing to be Seen at Bunker Projects showcases Centa Schumacher’s latest attempts to dream inside a lens. Having abandoned “the use of the camera as a factual recording device,” Centa’s photography asks about the slenders and rounds of light delayed and distracted by faults in the lens — a lens formed of “cast-off glass elements.” While camera manufacturers promise sharper, crisper, more perspectivally-fastidious images, Centa returns the lens to its origins — the lentil.

‘Lens,’ as a noun describing a curved piece of optical glass, was first used in print in 1693. The word, etymologists surmise, derives from the Latin term lens, meaning lentil. The clarity of modern lenses is what obscures this etymology, keeps it from being something you might guess in a round of pub trivia. The glass lens is named for its form rather than its transparency. Many of us encounter lentils through their economic, utilitarian meaning as food. Before and away from the dinner table, though, lentils are seeds. Unlike the lenses who borrowed their name, lentils do not pass light along with minimal interference. They turn it into heat, open themselves up, and then eat the sun.

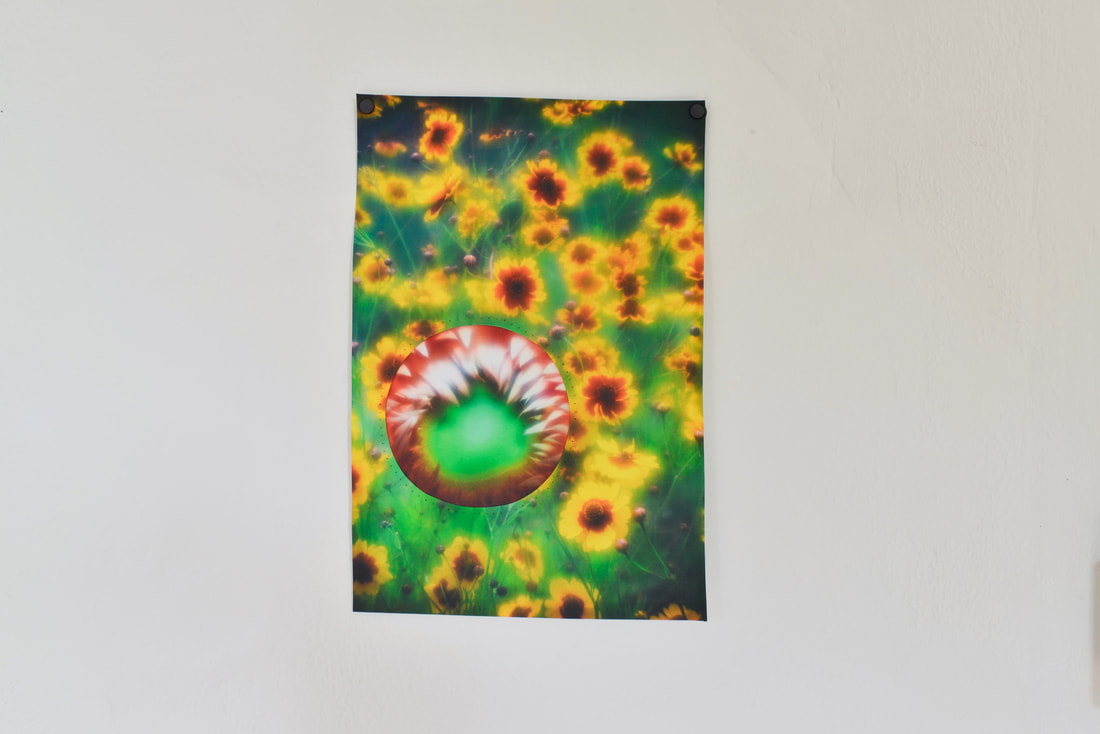

The lens in It is longing to be seen is active, responsive to the sun. The show features Centa’s signature use of a light-focused lens which magnifies bubbles, splits open radials, and bulges an otherwise linear path of glow. There are deep condensations of white and blue, membranous grays. Works like Sun’s Eye (2) (2023) continue these operations while introducing new, post-printing alterations to the lens. Curious prismatic circles cluster around something seen elsewhere at another time — a compound flower in shocking orange, pink, and yellow. This larger image has been cut open and this secondary image, an extreme close-up, has been sewn in. Simple points of thread hold it in place. The effect is something like a second lens on a magnifying glass. At any distance from a single object, only one lens can resolve into a clear representation. Other works, like Parabolic Superposition (2023), push past the artist’s established style and layer floral close-ups on one another. The print has the haze of a nostalgic flashback, and repeats the content of Centa’s standard work (repeating circular forms), rather than echoing her process through glares of light. In between, prints find different points in the photographic process to disrupt the expected fidelity of a camera image. Deep Field, by hand (2), (2023) works on other levels, bringing a patch of flowering Coreopsis into contact with something (botanical, surely) reminiscent of lamprey teeth. It is longing to be seen also signals Centa’s interest in a change of substrates: each print is on cotton rather than paper. The internal tension of warp and weft produces another disruption of clarity. Held against the wall with simple magnets, the cotton does what hung fabrics do. It slopes and slouches at points, pulls away from the wall. The cuts and hems of each print are tidy, however, keeping our focus on the upsets of the lens rather than a general treatise on fraying, coming undone, or decay. Continued manipulation of fabric in Centa’s work will, almost undoubtedly, add depth to this new material choice.

Centa Schumacher, Deep Field, by hand (2), (2023)

Centa Schumacher, Sun’s Eye (2) (2023), Installation view at Bunker Projects

Centa Schumacher, Itself (2023), at Bunker Projects

In her statement on the show, Centa writes that she is focused on, “the cold light of space pushing against the lush yielding of flowers in full bloom.” Both instances involve solar light — impossible to replicate in its physical intensity and its psychological meaning. Georges Bataille, a French writer of the early 20th century, offered that there are two suns for most of us: the sun we try to see only indirectly (in the colors of a flower at noon) that we treat as an apex; and the sun that some occasionally dare to study directly, lids ajar. This second sun, seen only in madness before blindness, isn’t the crown of the sky or the head atop a body. It’s “refuse or combustion.” The sun doesn’t give life as much as it is excess. Human cultures are ongoing attempts to constrain that excess, put it to work. A few actions circumvent this most Protestant of approaches to the sun: some sex, most (literal) sacrifice, the odd poem. Much high-profile, contemporary photography looks (and sometimes feels) like work. The camera is pointed at someone with a problem, or a place on the verge of becoming space, and a story is extracted, printed, circulated. There are historical reasons for why we say the camera “shoots,” but it more often seems to work like a vacuum. It pulls things in. More and more, I start to believe the old superstition that the camera steals from you, locks a part of you away from yourself.

Centa Schumacher, Sun’s Eye (1), (2023)

It is Longing to be Seen offers images which, if they aren’t heading away from work and towards the other sun, at least evoke something explosive, like “refuse or combustion.” Sun’s Eye (1) (2023) is a stitch-up of two photos, like the rest of the show, and the larger image is something like a hand lens put to up an eyeglass lens, held over a microscope viewfinder. Traces of things out-of-focus appear with smears and bubbles. The light is angular. It’s not a story from out there, but something more immediate. Language becomes clumsy. In the top left quadrant is the inset circular image: another cluster of floral greens, yellows, and pinks. It’s a sort of eruption of one photograph through the other. Floral repetitions aggressively pattern the space, but they’re gently blurred and fail to achieve dominance as a focal point. The combined image has no obvious center. How you move through Sun’s Eye (1) is a matter of how you respond to the desire the show names: a longing to be seen.

Centa Schumacher’s move into fabric prints, and her incorporation of botanical imagery, signal new ideas in her practice of putting the lens — rather than the film or the print — at the center of photography. What the fabric will come to mean in relationship to the photographic image, if anything, is unclear. Likewise, we’ll wait — longing to see — whether her florals will blur into abstraction, or sharpen into analogies for the floating lights in her past work.

Dani Lamorte

is a Pittsburgh-based artist. More: www.danilamorte.com.