Edited by Anna Mirzayan |

Original Publish Date: 12/12/2021

Kristin Virsis, “Peonies” (n.d.)

Images provided by Let’s Get Free and Brew House Association

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

Let’s Get Free’s fifth annual art show, “Empathy is the Seed, Truth is the Water, Solidarity is the Bloomage,” opened at the Brew House Association on Pittsburgh’s Southside on November 19, 2021. The show features 91 works from 34 artists in prison, and 35 artists outside of prison, most of whom responded to the show’s title. The interwoven themes of empathy, truth, and solidarity alongside images and inspiration from the natural world invite viewers to reflect on the complexity of freedom, and the inherent interdependence of the many strands of injustice tangled inside the prison industrial complex.

The show’s title means the gallery is full of lush, fertile imagery alongside decay and mystery. In pieces like Jane Hein’s stained glass “The Power of Nature” (2021), Kristine Virsis’s “Peonies” (2021) screenprint, and Marius Mason’s watercolor portrait “Edith Dorothea (Life After FSL)” (2021), which all feature various flowers, the artists use environmental imagery to illustrate the liberation and lessons found in nature. There are also several pieces that show an artist’s eye moving toward an industrial landscape or gray machinery. This duality of both environmental promise and environmental destruction remind viewers not to look for easy, hopeful messages in the ephemeral moments of bloomage or redemption stories, but to linger in the complexity of hope in the face of deadly serious violence. That balancing act is difficult for artists in prison, along with artists who make work about prison. Instead of falling into narratives of despair or redemption, this show, because of its scope and sincerity, manages to bring a harmonious, but challenging balance to that high-wire act.

Nichole “Pariah” Hollingsworth, “Bloom Where You Are Planted” (2021)

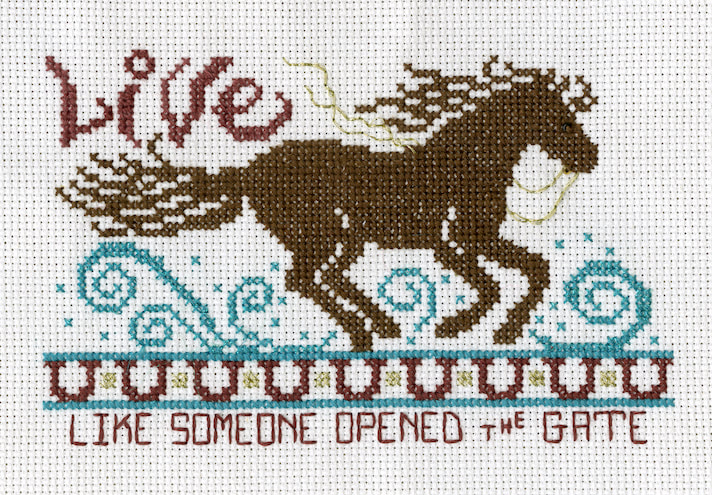

One of the material connections between artists on both sides of the wall is fiber and textile art. Needlepoint, crossstitch, quilting, felting, sewing, and weaving are on display throughout the gallery. The artists use these media to speak directly to viewers, whether in the cross stitches of Betty Heron, Amy Pencille, Marsha Scaggs and Latosha Gross, or in the banner made by Andrea Narno. In Jen Gooch’s tapestry “Redemption” (2018), woven from 30 letters exchanged with people in prison, the material transformation reminded me in the best way of the People’s Paper Co-Op in Philadelphia blending expunged criminal records into new paper pulp. Ginger Brooks Takashi’s embroidery on paper, “I Lift You Up” (2006) gives a ghostly, quiet quality that requires a viewer to get close. There are many more beautiful examples of fiber art that make good on the show’s aim of connecting artists on both sides of the prison walls, in this case through a marriage of materials.

The fiber art pieces also speak to important issues within the prison system. The presentation of “women’s handwork” carries the historical connotations of domesticity, leisure, and craft-based artistry that have long been dismissed in the world of fine art. In this show, these pieces are honored and elevated. They ask viewers to confront gender and the ways in which it impacts incarceration. From domestic violence, sexual assault, motherhood, and the astronomical rise in women’s incarceration since the War on Drugs, these pieces were some of the most moving in the show. If the medium reminds viewers of their grandmothers, it is perhaps no coincidence. Some of the women who created them are grandmothers themselves, having served enormous stretches of time.The old fashioned and traditional methods used to create these speak also to the growing numbers of elderly people incarcerated by methods like Death by Incarceration (a term used by prison abolitionists to describe the sentence of life without the possibility of parole), one of the many issues that Let’s Get Free advocates for in their activism.

Betty Heron, “Live like…” (2021)

In addition to the fiber art, pieces throughout the show directly use materials commonly found in jails and prisons to convey their message. Jurijus Kadamovas’s pieces, “Our Kind of Society” (2021) and “We As a Society” (2021) incorporate chunks of stucco from the walls of his death row cell into the conceptual, abstract, and graphic images he draws. Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli’s piece, “Instant Coffee” (2020) was created using the instant coffee packets found in lockdown bags, which are bagged breakfasts given during a lockdown. “Wishing Wells” (2021), by Bruce Bainbridge uses prison tongue depressors.

Todd (Hyung-Rae) Tarselli, “Instant Coffee” (2020)

It might be easy to dismiss these kinds of material uses as obvious bricolage, the kind of ingenuity that’s born of scarcity and demonstrates the deep humanness of art making. It’s easy to say human beings will find ways to express themselves, make marks, and show proof of their existence in even the bleakest circumstances. That much is obviously true. But as I viewed them, I also came away with the uneasy sense that I had to now exist next to a prison wall, imagine the physical sensation of medication checks pressing against the tongue, taste the coffee grounds of a lockdown–that the materiality moving outside the prison walls was not simply an act of inspiration, resilience, and ingenuity, but one that challenged me to reflect on the banal violence of a cup of coffee in a cage.

Photograph of opening night of “Empathy is the Seed, Truth is the Water, Solidarity is the Bloomage” at Brew House Association, provided by Brew House Association.

One of prisons’s qualities is alienation–alienation from the outside world, and alienation from the self. Shows like this one push against that alienation and toward connection, intimacy, and community. The works in the show represent the internal power of the artists and the power that comes in gathering them together, in conversation and community. The curation of the show puts the pieces in dialogue with each other, challenging viewers to make connections between the artists whose work was created in prison, and those whose work was created as an act of solidarity. In addition to the physical gallery space, the show also has a vibrant life online, at creative-resistance.org, which includes a virtual gallery, artist statements, an auction, and a contest to vote for artists whose work best exemplify the themes of the show. In a show this dense and diverse, the supplemental online materials help contextualize each piece, and invite viewers to linger in the diverse motivations, methods, and material of each artist. Despite the incredible diversity of the show, the thematic focus unifies the artists and makes for a cohesive, moving, and evocative showcase that celebrates the possibility of art-making as an act of resistance, survival, and love.

Well-known scholar and anti-prison activist Ruth Wilson Gilmore has written that “abolition is inherently everything-ist,” in that it requires the whole of human and environmental connections to build new conditions in which prison is not the answer for all of society’s harms. “Empathy is the Seed, Truth is the Water, Solidarity is the Bloomage” illustrates this everything-ist orientation with joy and abundance. This show embraces the more-is-more, everyone-is-invited, all-hands-on-deck approach to imagining new futures. It extends to viewers a compassionate, urgent invitation: let’s get free.

Sarah Shotland is the author of the novel Junkette and the creative nonfiction project Abolition is Everything. She is the cofounder and program director of Words Without Walls, which brings creative writing classes to jails, prisons, and treatment facilities in Western Pennsylvania.

Let’s Get Free is on view at Brew House Association until December 19, 2021. A poetry reading will be held on Monday, December 13 at 7:00pm, and the website will continue to be available to explore the works of these artists indefinitely. To learn more about Let’s Get Free and their expansive work, visit https://letsgetfree.info.