4/13/23

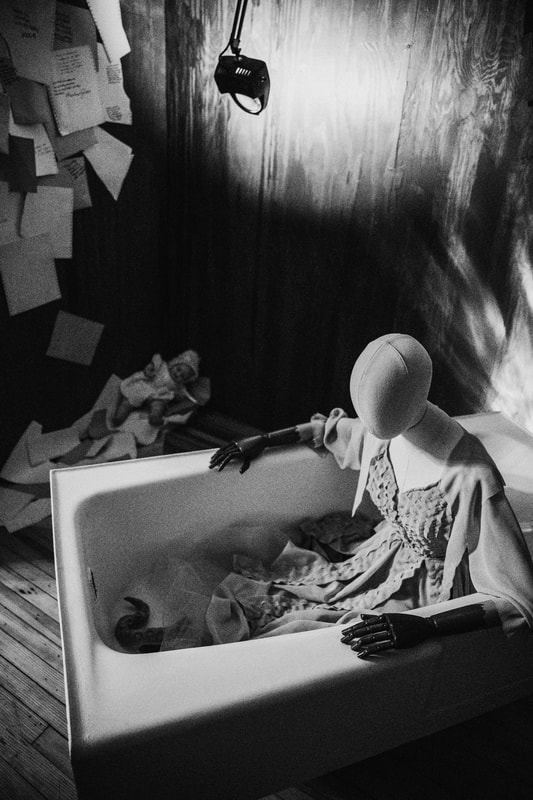

Installation view of

Amanda Filippelli, Astral (2023), at Alithi Studios

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members. All images courtesy of Amanda Filippelli.

There is no active voice for being born. In the grammar of the English language, a person can give birth, but “born” is a verb tense that can’t exist without the infinitive “to be” in front of it. Dying, arguably, has an active voice. A person dies. Sometimes they have died or are dead, but the simplest construction is to say they died. Full stop. That birth is passive and dying is active feels out of line with most of our conceptions (now there’s an interesting word!) about birth and death. Birth is a beginning, death an end. A beginning is an active choice. An ending is forced upon you. Artist and writer Amanda Filippelli inhabited these huge, confusing contradictions when her pregnancy with her son, River, coincided with her father’s unexpected death. That contradictory miasma of grief and joy was the genesis for The Remembering Room, Filippelli’s interactive 2023 installation project at Atithi Studios in Sharpsburg.

Installation view of Mnemosyne (2023), atThe Remembering Room opening

Filippelli built the entire installation in her late father’s basement studio, using parts of plastic models of superheroes and science fiction figures he constructed himself. Those plastic models provide the first look of the installation as you walk into it—but they don’t appear as Filippelli’s father originally created them Wolverine claws out of a mirror, torso-first, flowers springing up at his abdomen. A wire spider web shoots from Spiderman’s fingers, reflected back to itself within the mirror. Frankenstein’s monster’s profile is pasted onto another mirror, cut down the middle, his left side only a reflection. But who’s to say a reflection is less real than its subject? Filippelli’s father’s figures all reflect life that is not life. Robots and Frankenstein’s monster and superheroes all toe the line of human existence and something else. Filippelli’s father died abruptly and unexpectedly, and one of the feelings processed through The Remembering Room is the shock at finding his body. The mannequins and figurines throughout the exhibit correspond to that surreal moment of seeing a body that is no longer living, yet still a body. “It felt so strange that these superhero figurines had a body and he didn’t,” Filippelli said. “They exit the mirror in the same way my dad left the world. Wolverine was the hardest to cut up, though,” she told me, from her living room while her son, River, placed small plastic food on my lap. First, a plastic avocado without the plastic toast, then plastic toast without the plastic avocado. I smiled down at him and told him toast is one of my favorite foods.

When people die, all that’s left of them is the time we remember, because they no longer occupy space. The Remembering Room reimagines the intersection of time and space. The afterlife, however you conceive of it, is an attempt to reconcile that fact. For The Remembering Room, Filippelli found herself researching Celtic, Mayan, and Viking ways of mourning and articulating conceptions of life after death. “Before all this happened, I had a major fear of death,” she recalled. “My dad and I really differed on spirituality and religion. This experience has brought me to a place where I can recognize the idea of an afterlife. It doesn’t matter to me anymore what’s logical—the quality of life is affected by belief, and I’m tired of fighting against that.”

Visitors to The Remembering Room are surrounded by a soundscape of Filippelli’s distant memories and personal relationship to what might come after. “There’s audio of this VHS tape from my childhood, the only one I have. But also these orca sounds, since as a kid I was obsessed with whales and the ocean. A lot of seafaring cultures have ancient myths about whales and their relationship to life and death,” she said. The fact that that marine soundscape is the first thing you hear as you enter a room called Desert is another way Filippelli plays with impossibility and the in-between.

Amanda Filippelli, Grief Womb (2023)

Amanda Filippelli, Desert (2023)

Grief Womb (2023), the third room of the installation, takes the form of a tree, a thing that humans know to be living but that doesn’t have aliveness in a way we can identify with. Filippelli invited exhibition goers to leave “artifacts” inside the hollow of the tree, whether written memories or objects that remind them of lost loved ones. In Grief Womb, multicolored lights situate you in a place that is neither day nor night, and ivy, one of the few plants that stay vibrant throughout all seasons, surrounds the tree sculpture. The artifacts sit within If you try to look closely at the objects or pages left inside the tree’s womb, the design of the space is such that your shadow blocks it. Filippelli herself does not even look at the objects donated to the exhibition. The experience of my own shadow covering the grief womb was a powerful one—it felt like a representation of how I might get in my own way processing grief and pain. Or, on a more macro level, how we as human beings get caught in our own egos in the face of the overwhelming cycle of birth and death.

Filippelli’s use of mannequins throughout the exhibition, one in a bathtub in Mnemosyne (2023), and the other in a rowboat in Astral, bring to mind how a period of grief can make you feel disconnected from the human experience everyone else seems to access so easily. In Desert (2023), a small frame of pressed flowers reads: These flowers lived and died in a season you still existed. The objects throughout the exhibition ask us what these words taken for granted—exist, live, die, birth, be—really mean. But despite the visceral, all-consuming emotion of the exhibition, Filippelli found herself a place of peace with its creation. “My first project like this, Blue Rooms (2018), made me cry and cry and cry, but this has been so different. I feel like I’m giving it away. As a person with depression, I think this is what contentment feels like. I feel empty in the best way. I took River through it and just felt like ‘Look what Mom did!’”

Amanda Filippelli, Mnemosyne, (2023)

Though The Remembering Room represents the stages of grief, it does not leave you at an ending. Rather, you start with the white mannequin in the bathtub, where Filippelli spent some of her darkest moments. By the time you get to Astral, a black mannequin of a ferrywoman sits in a boat, surrounded by candles and crowned in a halo. The ferrywoman sits dressed in black, no matter the time of day. Sunshine does not brighten her. Her candles do not dim. But what strikes me the most is that in Desert the figure starts in the bathtub, the hot water contained in porcelain and the world around her dry air, and when I get to Astral, the figure is surrounded by water. In Filippelli’s specific experience of it, grief was a connection to a larger natural cycle–something often difficult for human beings to really understand, something as large as an ocean and as vast as a forest that still made her feel powerless and tiny and trapped. I asked her about the difference between the feeling of grief and the feeling of depression, given her professional history in mental health counseling. “Grief made me feel small. It makes you realize how much you’re a part of this bigger thing,” she said. “Depression is purposeless, but grief, you know where it comes from. Grief didn’t take away my motivation, it made me want to do things even as I felt that piece of me was missing.” Being in the confines of a boat surrounded by an endless ocean is profoundly lonely, as is shrinking into a hot bath surrounded by an overwhelming world. Sometimes life is boats, and other times it’s bathtubs. But the thing about water is that it’s also in 75% of the human body, so whether we are submerged or afloat, Filippelli shows that even in the deepest moments of isolation we are never truly alone.

The Remembering Room is on view at Atithi Studios is April 16th.

Emma Riva is the managing editor of UP, an international online and print magazine that covers the intersections of graffiti, street art and fine arts. She is also the author of Night Shift in Tamaqua, an illustrated novel set in the Lehigh Valley, and a contributor to Belt and Widewalls. More about her work can be found on her website and Instagram.