Edited by Harrison Kinnane Smith and Anna Mirzayan

Original Publish Date: 9/1/2021

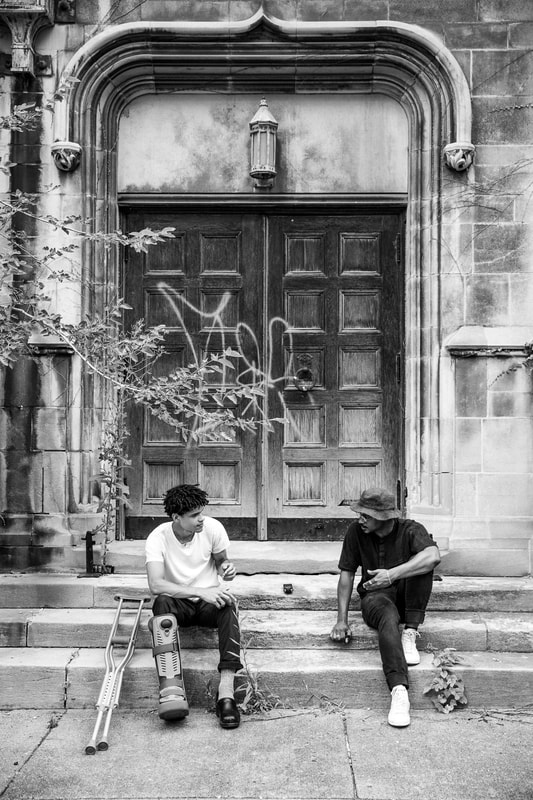

Photographed by Jared Piper

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

https://w.soundcloud.com/player/?url=https%3A//api.soundcloud.com/tracks/1123948255&color=%23505050&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&show_teaser=true

Bunker Projects · Justin Emmanuel Dumas in Conversation with Harrison Kinnane Smith

Earlier this month, I spoke with artist Justin Emmanuel Dumas in the wake of his exhibition Automatic Reliquary at Bunker Projects, and in anticipation of his upcoming installation Good / Bones at the Mattress Factory Museum. Together, we walked the length of Formosa Way in Homewood, passing St. Charles of Lwanga Cathedral and Holy Rosary School, where Dumas attended middle school.

Harrison Kinnane Smith: So the cathedral is no longer in use?

Justin Emmanuel Dumas: Yeah, it’s no longer in use. They said it’s in a good amount of disrepair, and they’re looking to sell it. It’s funny because, even having that church life growing up, a lot of the places that we would have service were really untraditional: in a house, or in a community center, a rec center… So a lot of times services wouldn’t be in quintessential churches or places of worship, so to speak.

HKS: How do you think that has affected your understanding of religion, and its role in your life?

JED: It made religion very personal, you know? It made faith feel like this thing that was flexible, that could always fit the context and the situation. It gave it a personal utility. It became useful for me in the way that it needed to be.

HKS: So what would you say your relationship to faith is now?

JED: It’s a great question, my relationship to faith now… I guess I’ve been looking for some of that in the work itself, and in some of the concepts that are present in the work. Having lost some matriarchs—spiritual cornerstones in the family—I’ve gained this voracious hunger, you know, for a kind of spiritual understanding. It sparked this search for evidence of the transcendent or something to give definite direction.

HKS: When you say that, “evidence of the transcendent,” what do you mean?

JED: I had a lot of encounters when I was younger, in particular with my mother who was a very spiritual person. I remember I would hear her praying on the phone with her friends at three o’clock in the morning. There was this level of conviction that I saw in people that I loved and cared about. That made me hungry to find and experience the things that gave them that same conviction. But at the same time, I was growing up in the church and seeing that people were people, that humans are imperfect. There’s a lot of things in between that make you question the validity of those beliefs and the truth of those convictions for those people… But that doubt and skepticism still wound up being a motivating factor in my search for something.

HKS: I’m also interested in the kind of transcendence you’re looking for. Are you looking for that feeling or experience in yourself? Is that the pursuit?

JED: I’m looking for it in the environment, in the places in the spaces around me. When I say the transcendent, I liken it a lot to this certain kind of synchronicity: a symbolic awareness where things that otherwise feel kind of banal or unimportant, still have this quality of being divinely orchestrated. There’s a great quote from Philip K. Dick, he says, “The symbols of the Divine show up at the trash stratum.”* From that, I get this idea: what you can’t find is where you refuse to look.

If there was any place to be certain about the presence of a kind of divine force, or divine encounter, it would be in the grime and muck, places that are otherwise overlooked. I grew up in cathedrals, churches, places that were designated as important and holy, but I still had doubt, I still had skepticism. So it was in the inverse where I was actually able to see that synchronicity and see patterns that felt like they added up to a greater meaning, that there is some kind of force orchestrating and organizing people and relations in places. I think those things become a lot more apparent and evident in those overlooked places, in that trash stratum, those grimy alleyways, those cuts and corners.

HKS: Can you give me an example of a moment or experience, or an object that you feel like you’ve identified as having that synchronous quality?

JED: I feel like this city is so filled with them. For example, a moment where you’re looking at a wall or a surface, and you see all these movements, these layers of human activity. There might have been a sign there, and then the sign was painted over, and then the sign was removed. And there’s still all these little moments of evidence of the activity that had occurred there. Those moments for me are transcendent, because they extend my awareness into a time that I wasn’t present. Or they extend my awareness into a situation that I wasn’t there to actually observe. So I guess that’s the tie for me between what would be faith-based evidence and the evidence of something real, that’s unseen, that you weren’t present for.

HKS: So in that equation, you’re drawing an equivalence between a connection to the divine and a connection to the social. Does that sound accurate?

JED: Yeah, but I would say ‘social’, public spaces that are collaboratively built and made. What you see when you’re looking at an old building, or an alleyway, or any surface that’s been around long enough, is kind of a group effort, whether or not people realize it. Things that arrive out of necessity, or just people living their lives, human agency. Marks and things that happen peripherally—they all add up with one another.

HKS: Let’s dive a bit more into the social. I think there’s a distinction to be made between the creation of social space or direct social engagements and the materially-mediated social connection you’re talking about where you’re reading into the human history of action upon a surface or an object. I’m curious about what your specific interest is in reading into that history, that mediated social experience? And how does it relate to what you’ve described as the transcendent or the divine?

JED: So that brings to mind the 20th century philosopher Walter Benjamin and his idea of the aura. Benjamin describes aura as a certain history or tradition and experience that radiates from an object—this comes from the essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935). He was essentially arguing for that there was a process of reproduction, and that it would strip objects of their aura. And he understood the aura as something to be pushed back against. So he felt that reproduction—mass production—would free objects from their aura, so that they could mean more things to more people. Of course, he’s writing and interacting with this in his historical moment. Here we are in the future, and I think very much living in a world influenced and orchestrated by that reproduction and that mass production, especially of the image and especially in digital spaces.

I’ve especially been thinking about that aura lately as something that an otherwise banal or mass produced object regains after having lived a certain amount of time.

I have another friend who works with found objects. And he said to me, “you know, you always choose stuff that you can find anywhere.” For me, that’s the point—that these objects are banal, but it’s their specific experience that has given them a certain patina and a certain finish that makes them worth finding and makes them worth picking up.

HKS: Can you talk a little bit about how that plays out in your work: How are these objects materially a part of the work? And how do you imagine all of those thoughts, that conceptual value, might be reflected in the work?

JED: It’s important to say that I’m not trying to emulate or replicate the surfaces and the influences that are out in the world. But they do teach me how to look and how to consider synchronicities when they happen in the works themselves. Here I’m thinking particularly about marks and gestures that occur out of necessity: maybe they’re gestures that you didn’t directly intend to be there, but by a process of having to screw these together or secure this with glue or make sure these two things are attached, you end up generating marks and gestures around them that are akin to that kind of narrative quality. When these objects find their way into the work, I’m looking for a similar kind of synchronicity, in objects and in surfaces that have that same kind of legibility or narrative on the surface.

HKS: What I’m hearing is that you’re really interested in these artifacts of labor, “traces of labor” (which I think is a phrase you use in the materials list of one of your works). But to have those traces, there has to be an independent labor narrative, right?

JED: I think that’s a great question. And I say this all the time: I feel like I’m constantly trying to get out of my own way—that is to say, to make decisions that aren’t necessarily aesthetic upfront… The goal of making something that is just visually pleasing, I think, can actually derail the process of trying to make something that has an actual narrative embedded into it, or has this legibility on the surface, if you will. The things that are inspiring and influencing these moments, they didn’t get there out of a desire to make something that’s visually appealing. They got there out of happenstance, just human agency and things that happen peripherally. And so I feel like that is a constant tension that I’m trying to resolve, because while I’m directly trying to make these objects, I’m still trying to have each gesture and each step happen somewhat peripherally.

In a nutshell, if there are things that I all knowingly put there, then there’s less opportunity for that synchronicity. And there’s less opportunity for me to come back to the work and notice something that I wouldn’t have, in the same way that I’m noticing these moments that are overlooked, you know, in this alleyway, and on the building surfaces around us.

I feel like it’s important to say as a final note that there’s a lot of complexity present in the concepts and in the language… But what I’m trying to achieve with the work, honestly, is very simple: I want people to see the work in these exhibition settings, and then leave with an attention to detail that will help them pay attention out in the world. Hopefully, the work gives people a certain set of eyes and a certain kind of attention that helps them see those same moments back out in the public space. For me, that’s the return to origin coming full circle—I’m thinking about taking the long way home, going out of your way to take the scenic route, and hopefully find those same moments of synchronicity and surface poetry.

HKS: Well, thank you for having this chat with me today.

JED: Yeah, thank you, bro. Appreciate you being here.

*Dick, Philip K. Valis and Later Novels. New York: Library of America, 2009. Print.

Both Justin Emmanuel Dumas and Harrison Kinnane Smith will present new installations of work in making home here, a group exhibition opening September 2nd at The Mattress Factory Museum.