Holding Still

Grounding the personal and political in The Front Yard by Bryan Martello | an essay by Helen Trompeteler |

A long time ago, when my partner and I started to seriously imagine a life together, we would daydream aloud about what kind of garden we would have – vegetables at the back, courgettes, peppers, tomatoes, and kale, perhaps. I would try to grow roses in the front like my parents had done in South London and my Nana before them in Harrow. Gardens or yards can be deeply personal spaces for continuing familial connection across generations, time or place. They can be powerful spaces for queer imagination in which self sustaining identities around home often transcend heteronormative gender expectations around nurture and the decorative. They can also manifest certain cultural conventions; moving from the UK to America a few years ago, I transitioned from traditions focused on family life in the privacy of the backyard to more public-facing porch and front yard traditions. These latter traditions inherently complicate the boundaries between public and private, personal and political, and these coexisting dichotomies are at the heart of Bryan Martello’s most recent series of photographs, The Front Yard.

In this new series, Martello uses his own yard as a studio space to construct scenes using personal and found objects and hand-made signs, and then photograph them using black-and-white film. This series marks a new direction in Martello’s practice, extending to the outside environment while still building upon themes from earlier studio-based constructions, which used color film photography, textiles, and installation to explore insular worlds related to pride, gender, and personal history. The Front Yard at first, appears to use a more streamlined visual language long associated with black-and-white photographic traditions. Yet, looking deeper at these photographs, one can instead perceive a slow unraveling of textual and visual languages, leading the viewer to question their role in shaping our lives and our histories.

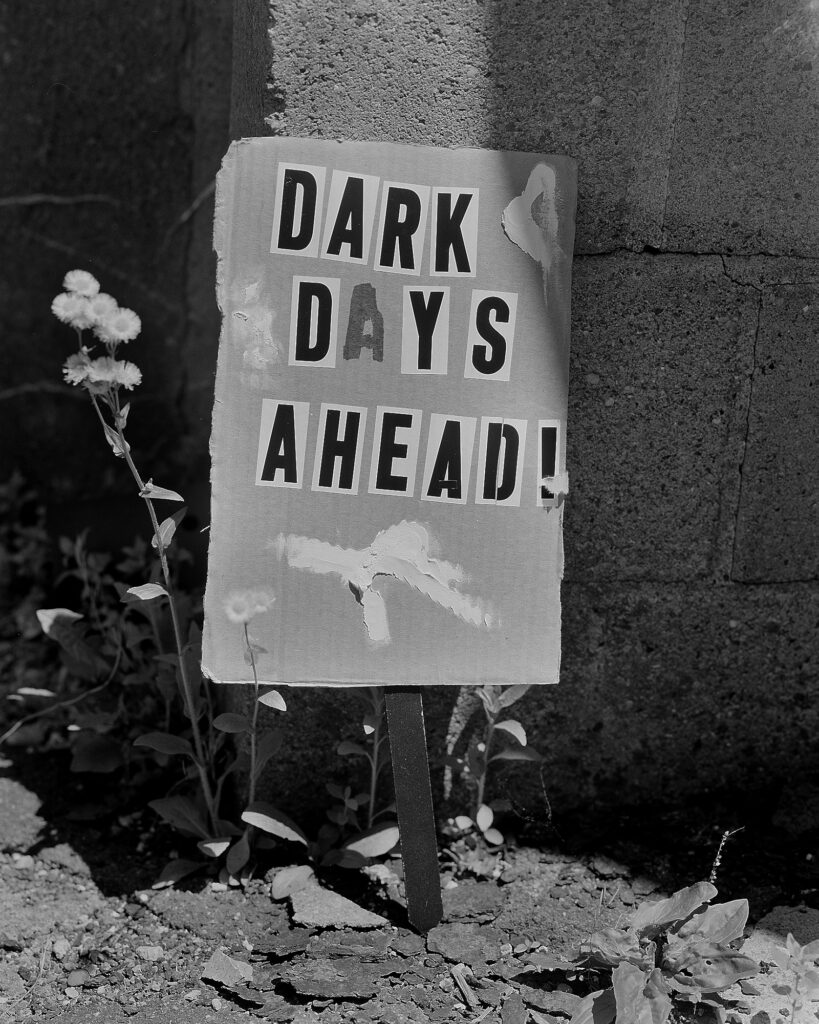

Throughout The Front Yard are photographs that utilize constructed signs, such as a handmade placard in Dark Days Ahead reminiscent of political and protest signs, or elsewhere recontextualized familiar household objects, such as an array of bottles and glassware in Fate. These photo-text works reflect the artist’s interest in using language poetically. Dark Days Ahead feels deliberately jarring with this archaic, almost biblical prophetic phrase, and this work points to the omnipresent contemporary fear-mongering and paranoia induced by the right to advance isolating political ideologies. Here, the artist leads us to contemplate how front yards become arenas for political expression, highlighting both the harmful consequences and activist potential of these spaces at a hyper-local level within our immediate surrounding neighbors and communities. Many of the photo text relationships in Martello’s photographs also have material qualities that emphasize tactility – hand-drawn, spray painted, improvised with tape or stickers – all of which leads us to think about the communicative properties of these everyday items.

Expanding further on the yard as a space to express or question ideologies, two individual photographs seem to invoke religious iconographies – beginning most clearly with a cherub plucking a guitar, illuminated in the darkness by the promise of love from above. A photograph of an upturned bathtub with scallop-shaped feet is a more ambiguous image that recalls statues of the Virgin Mary, colloquially known as ‘Bathtub Madonnas’. These evolved during the 20th century as a proud expression of Roman Catholic faith and cultural identity, especially in Italian American neighborhoods. However, the bath does not sit upright here to frame a statue of the Virgin Mary, Jesus, or a Catholic saint with its curved outline. Instead, in this photograph, it is empty, filled from below by the soil and its earthy nutrients. This composition, ladened with religious references, implies baptism and religious faith do not guarantee renewal. Instead, the photograph speaks to being grounded in the domestic spaces we claim for ourselves and in those with whom we hold faith to build a secular life.

Additionally, the figure of an owl also speaks to secular spirituality drawn from the natural world. Owls are often associated with talismanic qualities, perceived and used as guardian-like figures to ward off evil and keep predators away. Sometimes, statues of such symbols are carried forward and reincorporated in domestic yards by subsequent generations of family members. The memories we embed in yard spaces through every choice of object we position or plant we grow can also be considered protection.

While photographs such as Dark Days Ahead and Fate introduce an overall sense of foreboding and impending crisis, elsewhere in The Front Yard are separate photographs that suggest hope and connection. Within the recent exhibition at Bunker Projects, a small, intimate photograph of a key, nestled perhaps in a hiding place known only to trusted individuals, brings ideas of safety and security, inviting us to contemplate the yard as a threshold between hospitality or hostility, and the unfolding or withholding of access.

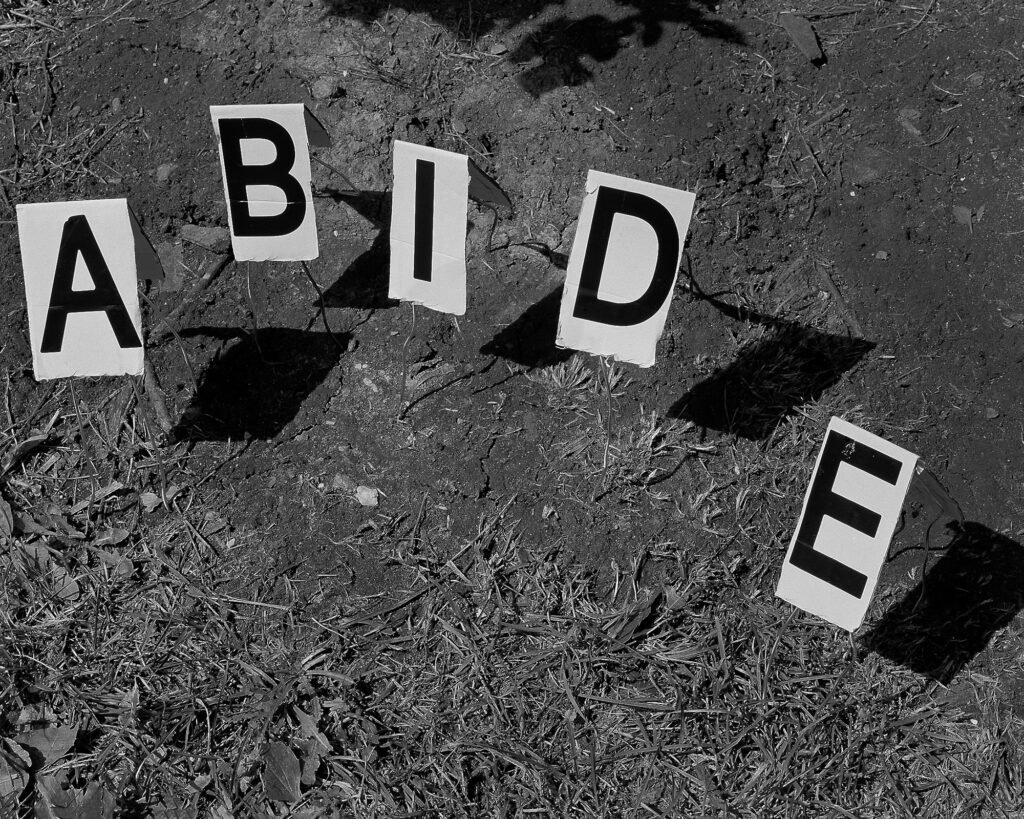

I lingered further on these ideas of intimacy when considering one particular juxtaposition in the exhibition between the photographs Abide and Flamingos, displayed alongside each other in a shared space on one dedicated wall of the exhibition. ‘Abide’ is visually isolated here, but it is hard to separate from its cultural associations with the well-known Christian hymn ‘Abide with me’, which offers a prayer for God to stay with its singer through life and death. Here, the isolated word ‘Abide’ is scattered on the ground with individual letters pinned down in an aesthetic that almost feels like markers of forensic evidence. Visual or textual language is always laden with potential meanings, but this particular image resonates powerfully with an aspect of queer experience. The composition of this photograph reminds me of how one actively follows a detective trail of visual, textual, or body language signifiers that indicate safety, welcome, or the possibility of kindred relationships.

Shown alongside Abide, I was intrigued by the immediacy of the framing and composition of Flamingos. Its shallow vantage point felt almost childlike in perspective and curiosity, the closeness to the ground accentuating the tactile and textural qualities of the earth. Two flamingos are out of focus in their physical bodily form but sharp and crisp in their adjoining shadows, implying a groundedness of intertwined inner lives. As elsewhere in Martello’s series, our focus is drawn back to earthly realms, inviting us to contemplate the environments that sustain and nurture us, whatever form they take. This juxtaposition of works reinforces themes I found meaningful throughout The Front Yard: the yard can be a powerful metaphor for the generative or resistive spaces we create at home. This can become even more of a radical act of love within queer experience as the home is a crucial space to nurture belonging and kinship, challenge conventions, and shape our inner and outward-facing lives.

The Front Yard is abundant in its potential meanings, and another photograph that I found especially compelling is Hold Still. The artist’s choice of props, chairs of woven plastic, feel incredibly nostalgic, recalling memories of the gardens of my early 1980s childhood and reinforcing both the yard as a space for familial connections and photography’s role in sustaining memory. The phrase ‘Hold Still’ is highly ambiguous, once again reflecting the artist’s interest in the nuances of language that can soothe or harm. Does this photograph convey the comfort of holding still and being unconditionally present? Perhaps it may represent a call for empathy, to hold still and listen? Or does it mean the polar opposite, a ring of alarm to hold still, withdrawing permission to move further physically or psychologically? I also cannot divorce this phrase from its photographic associations around power and agency. When we ask to make someone’s portrait, we frequently ask them to hold still, which verbalizes the power dynamic between the one observing and the one being seen. Ultimately, perhaps this photograph, in all its nuances, is directly challenging us to dismantle such dynamics inherent in photography itself. In doing so, the artist further emphasizes the home as a space where public and private tensions and the relationships between the gaze and representation are in continuous negotiation.

A sense of the surreal is an emotive undercurrent throughout The Front Yard. The role of the surreal or absurd philosophically is the conflict between the human desire to find meaning in the world around us and the impossibility of ever resolving this search. The storytelling I found within these photographs provides a meditative space to sit with the discomfort of this duality and, in doing so, edge a little closer to accepting this contradiction of human experience. Ultimately, I carry the multiplicity of these photographs’ layered meanings forward, feeling more empowered in my faith in the domestic space and yard as a place to express self-identity and memory, and to sustain the personal and political value systems that ground our lives.

Helen Trompeteler is a curator and writer deeply committed to supporting underrepresented artists working with photography, as demonstrated by decades of curatorial leadership experience, passionate arts advocacy, and extensive writing for publications worldwide. Born in London, Helen’s European heritage and her grandparents’ experiences of migration shaped her early life. Since 2020, she has proudly called Pittsburgh home, where she lives with her partner, Liz, and their dog, Elam.