Zoe Scruggs, Before We Knew(2022), acrylic on canvas

05/09/2022 Edited by Anna Mirzayan | Photos courtesy of the author

The views and opinions expressed in this article are solely those of the author. They do not reflect the opinions or views of Bunker Projects or its members.

The 2022 CCS student-curated show Interference opened on Saturday, April 2, at the Hessel Museum in Annandale-on-Hudson, NY. Among the 14 graduate exhibitions is Sofia Thieu D’Amico’s Up River Studies: Carcerality and the American Sublime, featuring paintings by multidisciplinary artist, musician, and farmer Zoe Scruggs (b. 1997), and Hudson River School painter Frederic Edwin Church (1826–1900), alongside extensive archival research by curator D’Amico on the history of convict labor and its role in the industrialization of upstate New York.

Curator D’Amico juxtaposes three newly commissioned paintings by Scruggs — a 2021 artist-in-residence at Bunker Projects — with works by the famous 19th century painter to underscore the artists’ often opposing expressions of traditional landscape painting. The marked differences in style, gesture, and materiality between Scruggs and Church allow for a re-imagining of the pastoral, idyllic representations of rural spaces common in landscape paintings of the 19th century. With Scruggs’s paintings, the viewer is invited to experience landscape anew, through her use of texture and mark-making in A Portrait Isn’t A Landscape, skewing the characteristic smoothness and perfect compositions of Church’s paintings. Scruggs also foregrounds figures in Before We Knew (2022) and Unlimited Life (2022), obliterating the painting tradition held during Church’s time of invisibilizing people, particularly laborers, from the land on which they live and work.

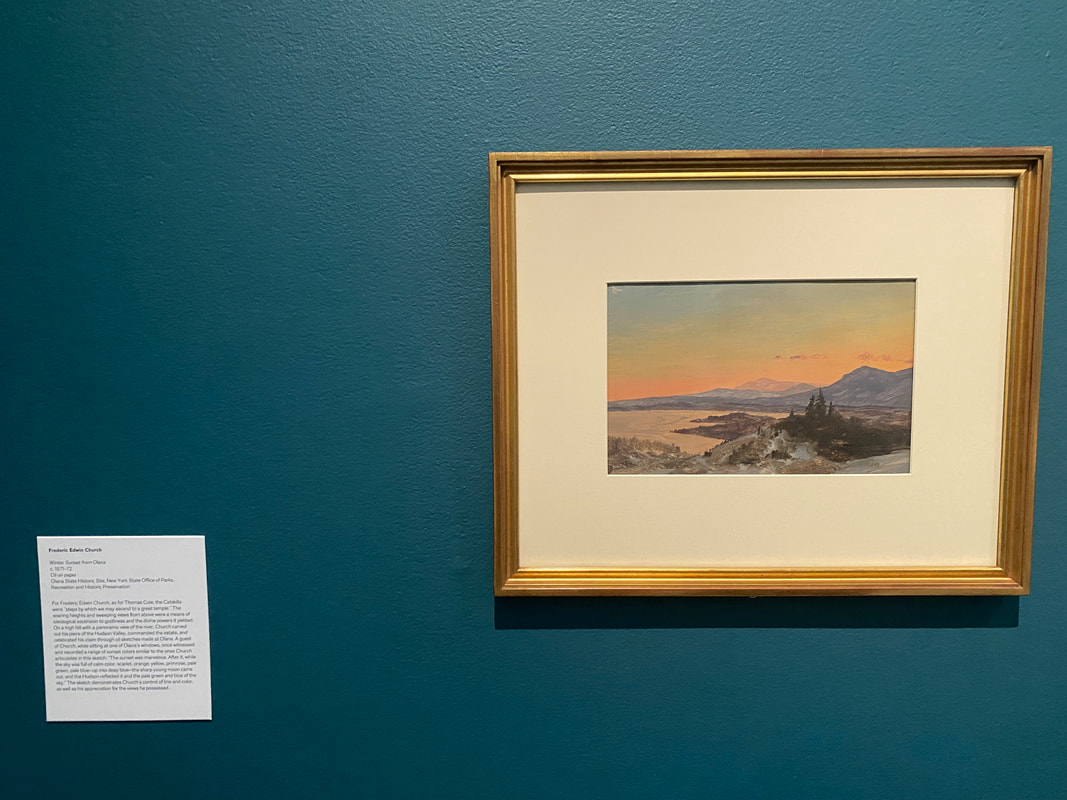

Frederic Edwin Church, Winter Sunset from Olana (ca. 1871-72), Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College

On one of the dark forest green walls of the gallery, which are reminiscent of the moody interiors of Church’s Orientalist mansion Olana, the viewer is greeted by Winter Sunset from Olana (ca. 1870-74). Nearby is Scruggs’s A Portrait Isn’t A Landscape (2022); its title alone undercuts the notion of what a landscape painting should be. The painting is a portrait of a bed of wildflowers in rose and gold hues among overgrown grasses that Scruggs also marks with rose and gold, along with varying greens and browns mixed with glitter and fake grass, resulting in a rough camo-like pattern. Behind is a sunny, blue sky, heavy with impasto and swirls of textural dots — made by seeds of actual wildflowers — and sequins from the artist’s mother. The collage suggests that the landscape that exists within this portrait is revealed in the materials and textures themselves.

Scruggs defiantly produces anti-landscape paintings by making her presence and influence as a painter known on the canvas. In Before We Knew (2022), two young children run through grass and bright orange vegetation with a slice of blue sky behind them, the same piercing blue as the children’s shirt and pants. What is most apparent is the line of horizon, which appears to be what one child peers at with her back to the viewer. She seems momentarily transfixed by what she sees in the distance that the viewer cannot see, and for a moment we are transfixed by what is beyond too. This desire to see beyond brings into question the static quality of landscape painting and offers an invitation into the possibility of the unknown. Is it possible that the landscape in Before We Knew has yet to be painted, or that perhaps only the child is privileged to see what lies beyond? The painting disrupts traditional power dynamics of who gets to experience beauty in nature and who does not.

Zoe Scruggs, A Portrait Isn’t A Landscape (2022), Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College

In Unlimited Life (2022), Scruggs upends the legal term “unlimited life,” used for assessing land value, by painting a portrait of her family among chartreuse grasses, tall trees, and a fiery backdrop reminiscent of a setting summer sun. Here, she suggests what an “unlimited life” could look like — a Black mother embracing her child and other family members engaged in leisurely activity, undisturbed. This particular image, among all of Scruggs’s works on view, seems to contrast the most with the archival documents articulating incarceration on an industrial level, because instead of appearing as utopic or idealistic of a possible world without this history of inequities, Unlimited Life exists in spite of them. Scruggs’s painting is a landscape marked by freedom.

Scruggs’s intentional deviations on the canvas are emphasized further through the numerous papers displayed throughout the gallery, which document in great detail the role convict labor played in the agricultural and economic development of upstate New York. One document on display, from the New York State Archives, proposes the construction of a new state prison on farmland with an elevated view of the Hudson river and such architectural qualities “where there would be no room or spaces which would not be thoroughly lighted through windows in the outer walls.” D’Amico also provides printed copies of Syllabus, a supplementary booklet of her comprehensive research into the history and expansion of New York state prisons with additional essays by Alan Michelson, Rowan Renee, and Cleveland Lovett. Citing Clarence Jefferson Hall’s A Prison in the Woods, D’Amico notes that “financially struggling towns and villages in upstate New York could not have otherwise afforded the numerous conservation, public works, and infrastructure projects without the low-paid work of incarcerated men.” This underscores the entanglement of leisure and forced labor in the same space.

Zoe Scruggs, Unlimited Life (2022), Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College

Frederic Edwin Church, Summer Sunset from Olana (ca. 1871-72), Hessel Museum of Art, Bard College

During the summer of 2021, still socially isolated from the COVID-19 pandemic and living in Hudson, I frequented Frederic Church’s Olana and walked along the many verdant, winding trails that encircled the house. One of these trails went along a picturesque pond where my dog enjoyed swimming after sticks I’d thrown for her in the shallow waters. After weeks of returning to our beloved spot, we took a different route and came across a sign describing the pond’s history: what was once woodlands that obstructed the view of the house up the hill became a scenic man-made lake dug by hand by Church’s servants, over the course of 20 years. Some of the fertile soil from underneath was later sold to make a profit. My relationship to this water immediately shifted with the knowledge of its history marked by labor. A part of me felt duped by the pond’s false natural beauty and presumed lack of invisible human labor. I kept going to the pond in spite of this history, though each time I thought about those human hands digging away at the earth to create beauty for someone else’s pleasure. With archival and natural materials, Up River dismantles the colonial-settler urge to convert something inferior into something of higher worth, in this case the wildness of the Hudson Valley — and delivers instead another view: beauty that is free in the face of laboring to achieve the sublime.

Shaheen Qureshi is a writer and editor. Born in Virginia to Filipino and Pakistani immigrants, her work has been published in Pidzn Club, Ewa Journal, Changes Review, Pinsapo Press, and elsewhere. She is the recipient of fellowships from Caldera Arts and MASS MoCA and holds an MFA from Bard College. She co-curates the reading series Here I Am Again, is co-founding member of artist collective SCAR, and works as associate editor at Carnegie Museum of Art.

Up River Studies: Carcerality and the American Sublime is part of Interference, fourteen graduate exhibitions curated by the M.A. candidates of the Class of 2022 at the Center for Curatorial Studies, Bard College (CCS Bard). It is on view at the Hessel Museum of Art April 2–May 29, 2022.